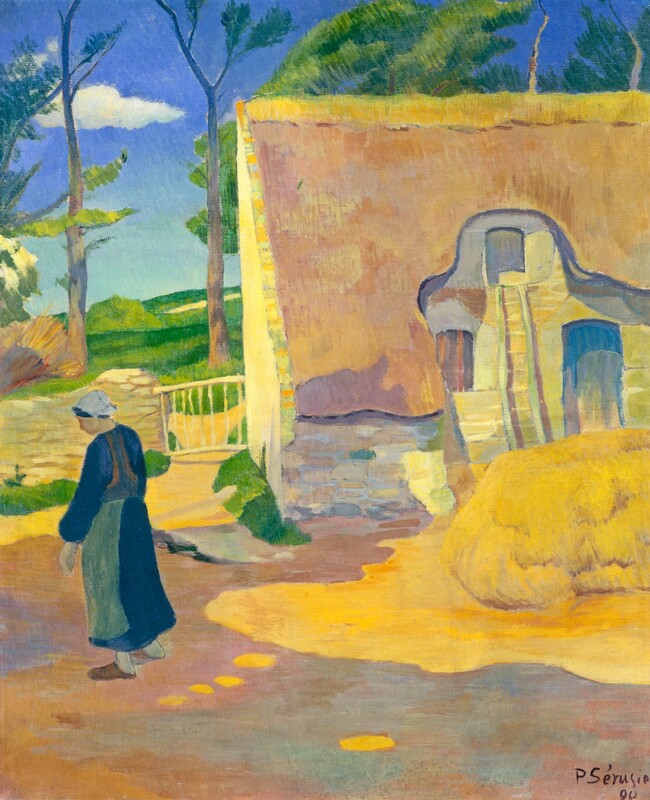

Farmhouse at Le Pouldu

1890

Paul Sérusier

Painter, French, 1863 - 1927

Paul Sérusier was born in Paris, and signed on as a student at the Académie Julian—the largest private art academy in Paris—in 1884. In the summer and autumn of 1888 he traveled in Britanny, where he visited for several weeks the village of Pont-Aven. At the Pension Gloanec, a gathering place of artists, he came into contact with Paul Gauguin. Gauguin and other painters were attracted by the remoteness of Brittany from the sophisticated art world of Paris, and they admired the relative simplicity of the Breton peasants' rural life, their picturesque regional costumes, and a traditional religious faith seemingly unchanged since medieval times. Sérusier soon became an intimate of the artistic circle around Gauguin, including Emile Bernard and Maurice Denis, who called themselves the Nabis (derived from a Hebrew word for prophet). They did not wish to capture the appearances of nature in a realistic manner, but rather to simplify form and color, and to arrange their sense perceptions into works of art that were decorative objects with a certain autonomy or independent artistic identity. Denis expressed these ideas most radically in his famous statement: "Remember that a painting—before being a war horse, a nude woman, or some anecdote—is essentially a flat surface covered with colors arranged in a certain order." [1]

Sérusier's Farmhouse at Le Pouldu is based on his observation of a typical Breton farmhouse, with a woman in local costume crossing the yard. But he has simplified shapes, flattened forms, and reduced the complexities of sunlight and dappled shade to broad areas of color, bounded by clear outlines. This flattening out of forms and the employment of sinuous linear patterns to unify the picture surface was sometimes referred to by the Nabis as "synthetism," denoting the idea of an artificial pictorial unity that sets the work of art apart from mere natural appearances. Sérusier's manner of painting is strongly influenced by Gauguin and Paul Cézanne, notably in the deliberately applied rows of short, finely hatched brushmarks, quite visible in the sky, trees, thatch of the cottage, and the pile of hay. Rather than the conventional pictorial subjects of farmhouse, peasant woman, farmyard, gate, trees, and the fields beyond, it is their decorative organization that forms the true subject of Sérusier's picture.

(Text by Philip Conisbee, published in the National Gallery of Art exhibition catalogue, Art for the Nation, 2000)

Notes

1. Maurice Denis, Définition du néo-traditionnisme, 1890.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 83

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

Gift of Alexander Mellon Laughlin and Judith Walker Laughlin

-

Dimensions

overall: 72 x 60 cm (28 3/8 x 23 5/8 in.)

framed: 101.6 x 88.9 x 7.6 cm (40 x 35 x 3 in.) -

Accession Number

2000.95.1

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

(Druet, Paris).[1] Hugo Troendle [1882-1955], Munich;[2] purchased 1925 by the Ulm Museum, Germany; (sale, Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett Roman Norbert Ketterer, Stuttgart, 29 November – 1 December 1955);[3] (Hermann & Günther Abels, Cologne).[4] sold January 1956 to Josef [1911-1975] and Hadassah [1912-1997] Rosensaft, Montreux, Switzerland, and New York.[5] Frank Lloyd, New York. (Marlborough-Gerson Gallery Inc., New York);[6] Mr. and Mrs. [1927-2020] Alexander M. Laughlin, New York; gift (partial and promised) 2000 to NGA; gift completed 2024.

[1] This name and that of “Professor Baum” are on a label on the back of the painting. However, Alexandra Chava Seymann, provenance researcher at the Ulm Museum, has kindly explained to the Gallery that Baum was never an owner of the painting; he was Prof. Dr. Julius Baum (1882-1959), director of the Ulm Museum from 1924 to 1933. She also suggested that "Druet, Paris" is likely the gallery owned by Eugène Druet (1867-1916); his name does not appear in the Ulm Museum's file on the painting. See her e-mails of 11 and 18 December 2017, in NGA curatorial files.

[2] This information, the additional details in note 3 about the painting’s ownership by the Ulm Museum, and copies that are now in NGA curatorial files of many relevant documents were kindly provided by Alexandra Chava Seymann (see note 1). Troendle was a German painter and writer about art, and it is possible he bought the painting from the Thannhauser Gallery in Munich, although there seems to be no records of this in the Thannhauser papers at ZADIK (Zentralarchiv für deutsche und internationale Kunstmarktforschung, Cologne). The painting was originally a loan to the Ulm Museum in 1925, as number L117, with the title Bretonisches Bauernhaus.

[3] With the rise of the National Socialist party in Germany in the 1930s, the painting was considered “Degenerate Art,” and, because he was Jewish, the Ulm Museum’s director, Julius Baum (see note 1) was forced out of his position. The painting was included in a 1933 list of works to be deaccessioned from the museum, and in the same year it was part of an exhibition at the museum, 10 Jahre Ulmer Kunstpolitik, meant to mock and defame Baum and his support of modern art and artists. The museum’s new acting manager made unsuccessful attempts to exchange the painting or sell it abroad, and in 1937 the painting somehow escaped the fate of over 200 works of art that were seized from the Ulm Museum and either auctioned off or destroyed. It remained in storage at the museum, and by 1950 the painting was again on display; a local newspaper article featured it: “Artwork of the Month,” Schwäbische Donauzeitung (15 June 1950).

However, in the early 1950s, with much of the museum’s modern art gone, the decision was made to focus on regional art, and to deaccession and sell works to raise funds for new acquisitions. A group of works from the Ulm Museum, including this painting, were sent to auction in late 1955; there is no record of the purchaser. See also: Brigitte Reinhardt, ed., Kunst und Kultur in Ulm 1933-1945, exh. cat., Ulmer Museum, Ulm, 1993: 60, no. 50.

[4] The Abels’s purchase of the painting at the1955 Stuttgart sale is documented in the Hermann und Günther Abels gallery papers (A-32) at ZADIK, Cologne. Copy of the inventory page kindly provided by ZADIK in e-mail of 26 February 2025 (NGA curatorial records).

[5] Sale date according to the gallery’s inventory sheet for the painting (see footnote 4). Rosensaft and his wife Hadassah Binkow were both Holocaust survivors who lived in Switzerland temporarily before moving to New York in the late 1950s. The painting was given as still with Rosensaft in the Sérusier catalogue raisonné (Marcel Guicheteau, Paul Sérusier, Paris, 1976: no. 23); however, it was not among those works sold by his estate on 17 March 1976 at Sotheby's, New York.

[6] Documents from the donors to the Gallery, in NGA curatorial files, appear to indicate the painting was purchased from this New York gallery, but they do not include a date.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1964

Possibly P. Sérusier, Durand-Ruel Gallery, Paris, 1964, no. 17, as Chaumière au Pouldu.

1991

Paul Sérusier et la Bretagne, Musée de Pont-Aven, 1991, no. 6, repro.

2000

Art for the Nation: Collecting for a New Century, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2000-2001, unnumbered catalogue, repro.

Bibliography

1925

Baum, Julius, ed. Führer durch das Museum der Stadt Ulm. Ulm, Germany, 1925: 96, as Bretonisches Haus.

1930

Baum, Julius, ed. Erster Bericht des Museums der Stadt Ulm. Ulm, Germany, 1930: 23, no. 117, as Bretonisches Bauernhaus.

1933

Reinhardt, Brigitte, ed. Kunst und Kultur in Ulm 1933-1945. Exh. cat. Ulm Museum, Germany, 1993: 60, no. 50, 223 nn. 10 and 11.

1976

Guicheteau, Marcel. Paul Sérusier. Paris, 1976: no. 23, repro.

Inscriptions

lower right: PSérusier / 90

Wikidata ID

Q20190126