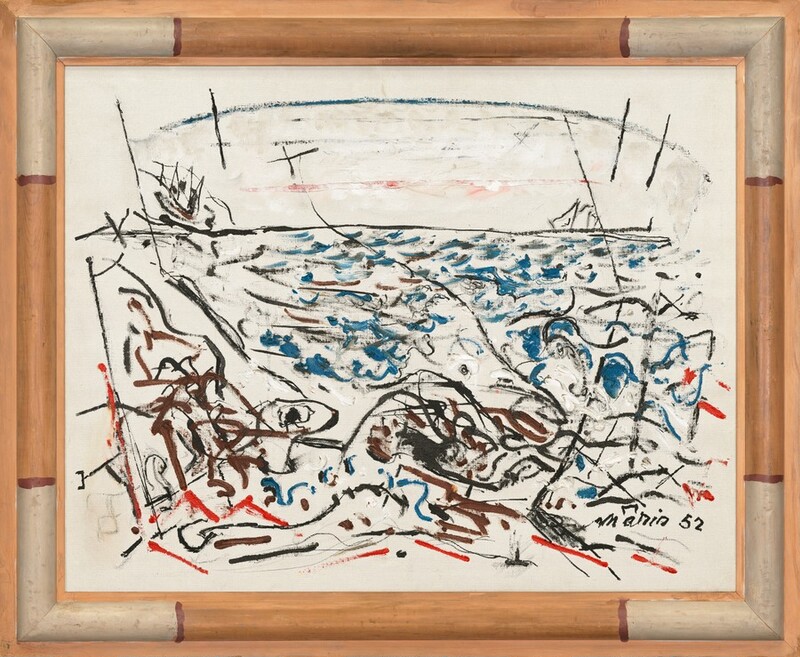

The Written Sea

1952

John Marin

Painter, American, 1870 - 1953

John Marin painted The Written Sea in 1952, when he was 82 years old, and it is considered one of the masterpieces of his late career, during which oil painting played a central role in his practice. His tendency toward abstraction by using a calligraphic line to capture a sense of the sea’s movement reflects his awareness of the younger painters of the New York school, such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, whose growing reputations would soon come to supplant his own. The painting retains Marin’s original hand-painted frame, designed to be an integral part of the composition that suggests the possibility of engaging in reflective and peaceful thought while looking out from the shoreline toward the tumultuous sea off the Maine coast.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 55.88 x 71.12 cm (22 x 28 in.)

framed: 68.58 x 83.82 x 3.81 cm (27 x 33 x 1 1/2 in.) -

Accession Number

2009.12.1

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

The artist's daughter-in-law, Norma B. Marin; (Meredith Ward Fine Art, New York); purchased 2006 by Deborah and Ed Shein, Providence; gift 2009 to NGA.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1952

John Marin Exhibition, The Downtown Gallery, New York, 1952-1953.

1954

John Marin, The Philadelphia Art Alliance, 1954, no. 44.

1955

John Marin, Art Galleries of the University of California, Los Angeles, 1955-1956, no. 36.

1956

John Marin, Arts Council Gallery, London, 1956, no. 29.

1970

John Marin, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1970, no. 154.

1987

Marin in Oil, The Parris Art Museum, Southampton, New York, 1987, no. 53.

1990

John Marin, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1990, no. 250, repro.

2000

John Marin: The Painted Frame, Richard York Gallery, New York, 2000, no. 34.

2008

John Marin: The Late Oils, Adelson Galleries, New York, 2008, no. 12.

2010

American Modernism: The Shein Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2010-2011, no. 12, repro.

2011

John Marin: Modernism at Midcentury, Portland (Maine) Museum of Art; Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth; Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, 2011-2012, unnumbered catalogue, pl. 57.

Bibliography

1953

Faison, Jr., S. Lane. “Art.” The Nation 176 (7 February 1953): 133.

Art News 51 (February 1953): 58.

1970

Gray, Cleve, ed. John Marin by John Marin. New York, 1970: 171, repro.

Reich, Sheldon. John Marin: A Stylistic Analysis and Catalogue Raisonné. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1970, pp. 235-236, no. 52.50.

1971

Hughes, Robert. "Fugues in Space." Time (22 February 1971): 62.

1987

Smith, Roberta. "Art: John Marin's Oils at an L.I. Museum." The New York Times (14 August 1987).

1988

Tuchman, Phyllis. "Another Marin." Art in America 76 (June 1988): 59, repro.

2000

Fine, Ruth E. "John Marin, an Art Fully Resolved." In Modern Art and America: Alfred Stieglitz and His New York Galleries. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2000: 351-352, repro.

2010

Brock, Charles, Nancy Anderson, and Harry Cooper. American Modernism: The Shein Collection. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2010: no. 12, repro.

Inscriptions

lower right: Marin 52

Wikidata ID

Q20194614