Imagination

1932

Oscar F. Bluemner

Painter, American, 1867 - 1938

A lifelong passion for his initial profession, architecture, along with a deep interest in German thought and the emotionally expressive potential of color informed Oscar Bluemner’s approach to his innovative paintings. Like other American modernists, he was strongly influenced by contemporary movements in European art and utilized rich hues and abstract shapes to celebrate the varied landscape of his adopted country.

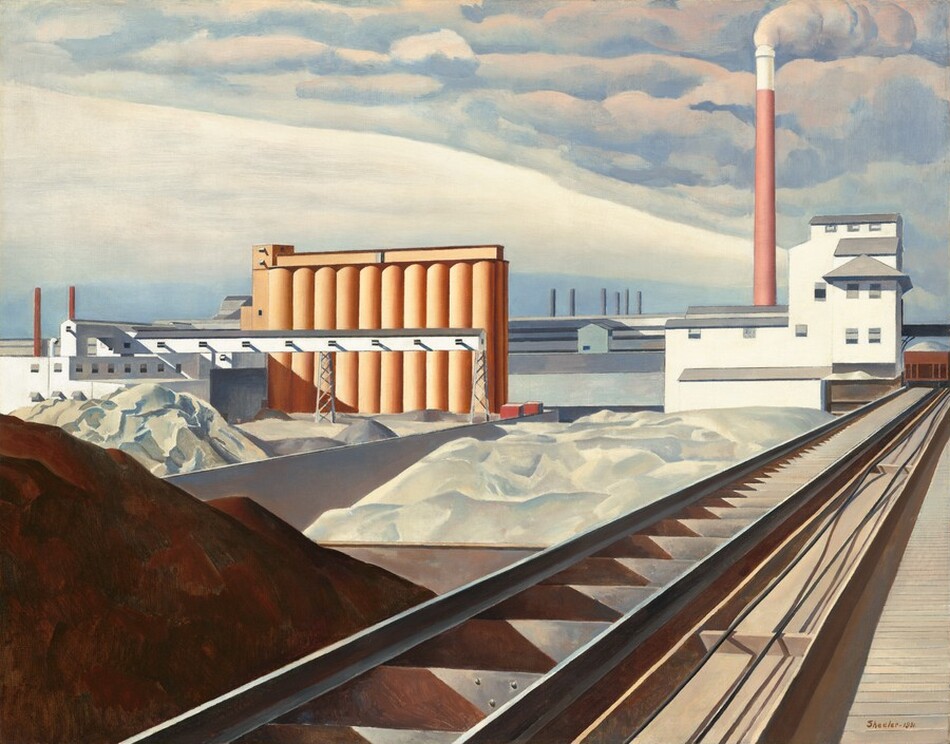

Executed near the end of his life and part of a series he called Compositions and Color Themes, Imagination exemplifies Bluemner’s singular approach to his subject matter. Instead of portraying an urban scene or tranquil rural vista, Bluemner has created a hybrid of the two, setting a vibrant red building in a lush green landscape and surrounding both with a night sky interrupted by flamelike passages. Just three years before composing this work, the artist had written a lengthy article in which the word imagination recurs and is linked closely to the power and beauty of painting. In his treatise, Bluemner wrote passionately about the color red and adopted the pseudonym “the Vermillionaire.” Imagination was included in Bluemner’s critically acclaimed yet commercially unsuccessful exhibition at New York’s Marie Harriman Gallery in 1935.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

casein and watercolor on paper, mounted to paperboard

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 79.38 × 58.9 cm (31 1/4 × 23 3/16 in.)

framed: 95.25 × 74.3 × 6.03 cm (37 1/2 × 29 1/4 × 2 3/8 in.) -

Accession Number

2015.19.161

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

The artist [1867-1938]; his estate. Robert C. Graham Jr., by 1969;[1] his son, Robin Graham; purchased November 1978 by (Barbara Mathes Gallery, New York); purchased 26 March 1979 by the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington; acquired 2015 by the National Gallery of Art.

[1] Graham is listed as the painting’s owner in the catalogue for a 1969 exhibition, Oscar Bluemner: Paintings, Drawings, shown at the New York Cultural Center. Graham was president of the James Graham and Sons Gallery in New York; a Graham Gallery label is on the backing board.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1935

New Landscape Painting by Oscar F. Bluemner: Compositions for Color Themes, Marie Harriman Gallery, New York; Arts Club of Chicago, 2 January - March 1935, no. 23.

1939

Oscar Florianus Bluemner, University Gallery, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, 2-28 March 1939, no. 11.

1969

Oscar Bluemner: Paintings, Drawings, New York Cultural Center, 16 December 1969 - 8 March 1970, no. 71, repro.

1976

Collector's Gallery X, Marion Koogler McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, November-December 1976, no catalogue.

1982

Acquisitions Since 1975, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 1982-1983, no catalogue.

1988

Oscar Bluemner: Landscapes of Sorrow and Joy, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington; Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth; New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, 10 December 1988 - 3 September 1989, no. 105.

2005

Oscar Bluemner: A Passion for Color, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 7 October 2005 - 12 February 2006, unnumbered catalogue.

2008

The American Evolution: A History through Art, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 2008, unnumbered checklist.

2009

American Paintings from the Collection, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 6 June - 18 October 2009, unpublished checklist.

2013

American Journeys: Visions of Place, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 21 September 2013 - 28 September 2014, unpublished checklist.

Bibliography

1933

Bluemner, Oscar. Painting Diaries 1932-1933. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Oscar Bluemner Papers, Washington, D.C., 1933: Reel 340, Frames 2172-2173.

1935

Salisbury, Frank. "Oscar Bluemner: Marie Harriman Gallery." Art News 33, no. 14 (5 January 1935): 5.

Breuning, Margaret. "Paintings by Bluemner at Harriman Gallery." New York Post (12 January 1935): 2.

1982

Richard, Paul. "Acquired Art: Corcoran Shows Its Best Since 1975 [exh. review]." The Washington Post (23 November 1982): D:2.

Hayes, Jeffrey Russell. "Oscar Bluemner: Life, Art and Theory." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park, 1982: 361-63, 377, 397 no. 164, 397 no. 165, 397 no. 167, 530 repro.

1991

Hayes, Jeffrey. Oscar Bluemner. New York, 1991: 154, 157 repro., 169, 185.

2000

Cash, Sarah, with Terrie Sultan. American Treasures of the Corcoran Gallery of Art. New York, 2000: 196 repro.

2011

Wingate, Jennifer. "Oscar Bluemner, Imagination." In Corcoran Gallery of Art: American Paintings to 1945. Edited by Sarah Cash. Washington, 2011: 242-243, 282, repro.

Inscriptions

lower right, the Ü formed by L and left edge of M, the outer edge of B extending down and below BL then up through M to form N, the ER in monogram: BLÜMNER; upper center right reverse: 'Imagination'

Wikidata ID

Q46634799