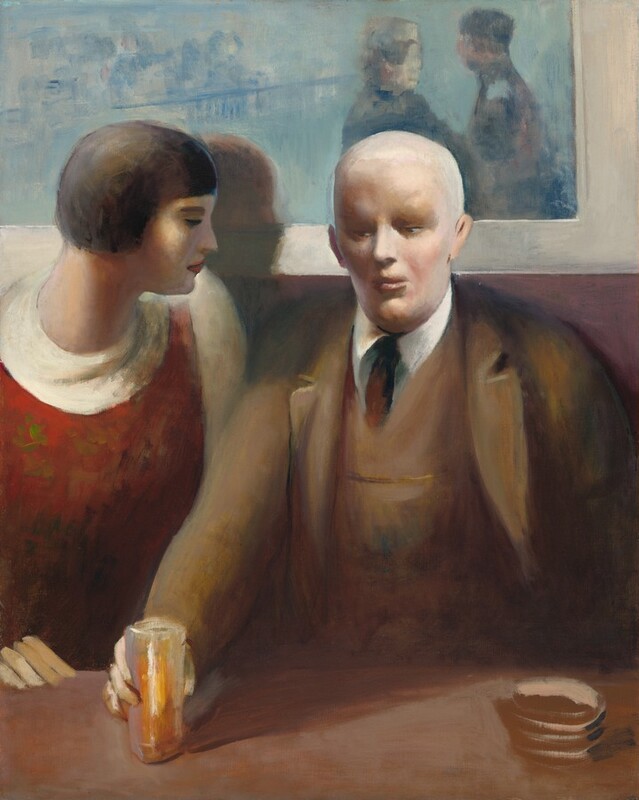

Pierrot Tired

c. 1929

Guy Pène du Bois

Painter, American, 1884 - 1958

Guy Pène du Bois painted Pierrot Tired while living in France in the 1920s. Although the artist’s strained finances forced him to live some 30 miles outside Paris, his fascination with that city’s café society and expatriate culture led him to paint many views of well-to-do restaurant and nightclub patrons. Here, a fashionably dressed couple convenes in a café, but despite their physical closeness their stiff figures and inscrutable, masklike faces suggest underlying social alienation. Moreover, their apparent emotional isolation and age difference invite the viewer to speculate about their relationship. Adding to the scene’s mystery is the presence outside the café window of a second couple who appear to be conversing with or brushing against each other.

At first glance, the painting’s title is as enigmatic as its subject. However, Pène du Bois likely was equating the melancholy man in his painting with Pierrot, the sad, lovelorn clown of the commedia dell’arte (and possibly more broadly with the artificial worlds of theater and high society). Pène du Bois would have been aware of the many commedia dell’arte performances in 1920s Paris and of representations of Pierrot in fine and popular art. For example, he may have encountered Jean-Antoine Watteau’s 18th-century painting of the clown in the collection of the Louvre museum. However, following Pène du Bois’s death his painting’s original title, and therefore its link to Pierrot’s popularity in 1920s Paris, was forgotten for 25 years until research revealed it in 1984.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 92.08 × 73.03 cm (36 1/4 × 28 3/4 in.)

framed: 113.67 × 95.25 × 10.16 cm (44 3/4 × 37 1/2 × 4 in.) -

Accession Number

2015.19.177

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Estate of the artist; (James Graham & Sons, New York), c. 1960. Karl Jaeger, Cambridge, Massachusetts; sold 1968 to (Vose Galleries, Boston); sold 1968 to (Bernard Danenberg Galleries, New York).[1] (sale, Christie, Manson & Woods, New York, 11 December 1981, no. 242, as Drink at the “Russian Bear”); purchased by the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington; acquired 2015 by the National Gallery of Art.

[1] A letter of 27 November 1979, from Robert C. Vose, Jr., to Betsy Fahlman, and an e-mail of 20 April 2004, from Siobhan Wheeler of Vose Galleries to Emily Shapiro of the Corcoran, in NGA curatorial files, provide the Jaeger-Vose-Danenberg sequence of ownership. The painting's inventory number at Vose Galleries was 22831.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1930

Exhibition of Paintings and Water Colors by Guy Pène du Bois, C.W. Kraushaar Art Galleries, New York, 26 February - 25 March 1930, no. 10.

1932

127th Annual Exhibition, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, 24 January - 13 March 1932, no. 439.

12th Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Oils, Cleveland Museum of Art, 10 June - 10 July 1932, unnumbered checklist.

45th Annual Exhibition of American Paintings and Sculpture, Art Institute of Chicago, 27 October 1932 - 2 January 1933, no. 62.

1939

An Exhibition of Painting by Guy Pène du Bois from 1908-1938, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, 4-22 January 1939, no. 37.

1961

Guy Pène du Bois 1884-1958, Graham Gallery, New York, 17 March - 15 April 1961, no. 16, as Drunk at Russian Bear.

1982

Acquisitions Since 1975, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 5 November 1982 - 16 January 1983, unpublished checklist.

1985

Henri's Circle, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 20 April - 16 June 1985, unnumbered checklist.

2004

Figuratively Speaking: The Human Form in American Art, 1770-1950, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 20 November 2004 - 7 August 2005, unpublished checklist.

2005

Encouraging American Genius: Master Paintings from the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, NY; Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte; John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, 2005-2007, checklist no. 87.

2008

The American Evolution: A History through Art, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 1 March - 27 July 2008, unpublished checklist.

2009

American Paintings from the Collection, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 6 June - 18 October 2009, unpublished checklist.

2013

American Journeys: Visions of Place, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 21 September 2013 - 28 September 2014, unpublished checklist.

Bibliography

1932

H. C. H. "The Twelfth Exhibition of Contemporary American Oils [exh. review]." Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art (June 1932): 105.

1984

Corcoran Gallery of Art. American Painting: The Corcoran Gallery of Art. Washington, 1984: 34, repro., 35.

1996

Abramson, Ronald D. "'My Favorite Painting': Discovering the Permanent Collection." Night and Day (July/ Agust 1996): 12, repro., 13.

2000

Cash, Sarah, with Terrie Sultan. American Treasures of the Corcoran Gallery of Art. New York, 2000: 179, repro.

2011

Roeder, Katherine. "Guy Pène du Bois, Pierrot Tired." In Corcoran Gallery of Art: American Paintings to 1945. Edited by Sarah Cash. Washington, 2011: 238-239, 281-282, repro.

Wikidata ID

Q46634628