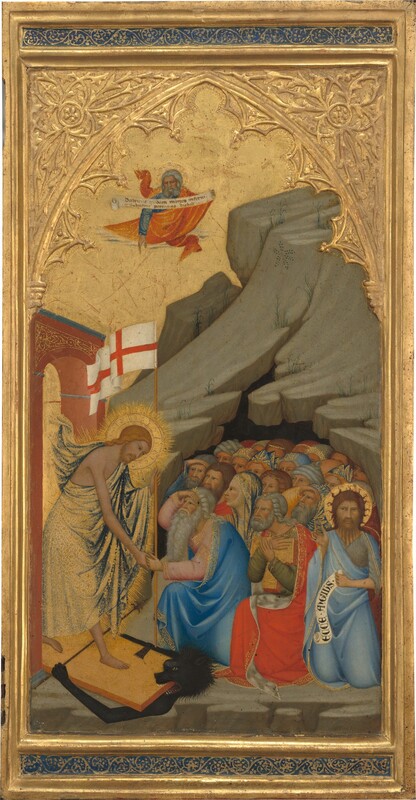

Scenes from the Passion of Christ: The Descent into Limbo [right panel]

1380s

Andrea Vanni

Artist, Sienese, c. 1330 - 1413

Between the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, Jesus is said to have descended into the realm of the dead where he liberated the Old Testament patriarchs and prophets. This event, known as the Decent into Limbo, is represented here on the right wing of a triptych by Andrea di Vanni. In Andrea’s interpretation, Christ the Redeemer has descended victoriously into hell, where he has demolished the gateway and crushed the devil beneath it.

The deep, saturated hues of red, yellow, and blue create rhythmic alternations of color that play against the gold backgrounds and halos to animate the scenes. Such dazzling effects accentuate the dramatic gestures of the figures, whose robust, naturalistic forms are carefully organized to express compelling human emotion and facilitate narrative legibility. The exquisite miniaturist quality of execution, dynamic use of space, and construction of depth exemplify a skillful conflation of elements derived from the previous generation of Sienese painters, particularly Simone Martini and the Lorenzetti brothers.

The altarpiece to which this panel belongs is comprised of three panels attached by hinges. The flanking panels can be folded over the central painting to protect it and facilitate transportation. As a portable altarpiece, Andrea’s triptych may have been intended for a small chapel or domestic interior where it could be displayed or concealed according to its owner’s requirements.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 3

Artwork overview

-

Medium

tempera on panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

painted surface: 47.2 × 25 cm (18 9/16 × 9 13/16 in.)

overall: 56.7 × 29.2 × 3.3 cm (22 5/16 × 11 1/2 × 1 5/16 in.) -

Accession Number

2014.79.711.c

Associated Artworks

Scenes from the Passion of Christ: The Agony in the Garden [left panel]

Andrea di Vanni

1380

Scenes from the Passion of Christ: The Agony in the Garden, the Crucifixion, and the Descent into Limbo [entire triptych]

Andrea di Vanni

1380

Scenes from the Passion of Christ: The Crucifixion [middle panel]

Andrea di Vanni

1380

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

William Andrews Clark [1839-1925], New York, by 1919; bequest 1926 to the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington; acquired 2014 by the National Gallery of Art.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1959

Loan Exhibition. Masterpieces of the Corcoran Gallery of Art: A Benefit Exhibition in Honor of the Gallery's Centenary, Wildenstein, New York, 1959, unnumbered catalogue, repro., as Portable Altarpiece.

1978

The William A. Clark Collection, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1978, fig. 27.

2002

Antiquities to Impressionism: The William A. Clark Collection, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 2001-2002, unnumbered catalogue, repro.

Bibliography

1921

Perkins, F. Mason, "A Triptych by Andrea di Vanni." Art in America 9, no. 5 (August 1921): 180-188, repro.

1923

Marle, Raimond van. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. 19 vols. The Hague, 1923-1938: 2(1924):443-445, repros.

1925

Carroll, Dana H. Catalogue of Objects of Fine Art and Other Properties at the Home of William Andrews Clark, 962 Fifth Avenue. Part I. Unpublished manuscript, n.d. (1925): 127, no. 58.

1927

Offner, Richard. Studies in Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. New York, 1927: 78.

1932

Corcoran Gallery of Art. Illustrated Handbook of the W.A. Clark Collection. Washington, 1932: 59, no. 2181.

Edgell, George Harold. A History of Sienese Painting. New York, 1932: 172–173, fig. 224.

1939

Pope-Hennessy, John. “Notes on Andrea Vanni.” The Burlington Magazine for

Connoisseurs. 74, no. 431 (1939): 97.

1943

Pope-Hennessy, John. "A Madonna by Andrea Vanni." The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 83, no. 484 (1943): 174.

1952

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Painters of the Renaissance. 3rd edition. Oxford, 1952: 268.

1955

Carli, Enzo. La pittura senese. Milan, 1955: 154-158.

1959

Corcoran Gallery of Art. Masterpieces of the Corcoran Gallery of Art. Washington, 1959: 8-9, repro.

1960

Francisci Osti, Ornella. “Andrea Vanni.” In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Edited by Alberto Maria Ghisalberti. 82+ vols. Rome, 1960+: 3(1961): 122–124.

1966

White, John. Art and Architecture in Italy, 1250 to 1400. Baltimore, 1966: 365.

1968

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance. Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London, 1968: 1:442.

1969

Bologna, Ferdinando. I pittori alla corte angioina di Napoli, 1266-1414, e un riesame dell’arte nell’età fridericiana. Rome, 1969: 325-326.

1978

Brown, David Alan. “Andrea Vanni in the Corcoran Gallery.” In The William A. Clark Collection: An Exhibition Marking the 50th Anniversary of the Installation of the Clark Collection at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington. Exh. cat. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 1978: 32–37.

Wainwright, Valerie Linda. "Andrea Vanni and Bartolo di Fredi: Sienese Painters in their Social Context." Ph.D. dissertation. University of London, University College, 1978: 145–146.

1979

Fleming, Lee. “Washington: A Guide to the Arts.” Portfolio (June/July 1979): 90, repro. 91

1981

Worthen, Thomas Fletcher. "The Harrowing of Hell in the Art of the Italian Renaissance." 2 vols. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Iowa, Ames, 1981: 102-104, 386 n. 29, 387 n. 31, fig. 49.

1982

Il gotico a Siena: miniature, pitture, oreficerie, oggetti d’arte. Exh. cat. Palazzo Pubblico, Siena. Florence, 1982: 287

1993

Gagliardi, Jacques. La conquête de la peinture: L’Europe des ateliers du XIIIe au XVe siècle. Paris, 1993: 106.

1996

Wainwright, Valerie. “Andrea (di) Vanni (d’Andrea Salvani).” In The Dictionary of Art. Edited by Jane Turner. 34 vols. New York and London, 1996: 2:21.

2001

Coyle, Laura, and Dare Myers Hartwell, eds. Antiquities to Impressionism: The William A. Clark Collection, Corcoran Gallery of Art. Washington, DC, 2001: 53, repro.

2002

Heartney, Eleanor, ed. A Capital Collection: Masterworks from the Corcoran Gallery of Art. London, 2002: 90.

2005

Schmidt, Victor M. Painted Piety: Panel Paintings for Personal Devotion in Tuscany, 1250-1400. Florence, 2005: 193, repro. 196, 203 n. 92.

2016

Paolucci, Antonio, et al, eds. Piero della Francesca: Indagine su un mito. Exh. cat. Museo San Domenico, Forlì, 2016: 82.

Inscriptions

in black paint on the scroll held by God the Father: Destruxit quidam mortes inferni / et subvertit potentias diaboli; in black paint on the scroll held by Saint John the Baptist: ECCE.ANGIUS[AGNUS]. (Behold the Lamb)

Wikidata ID

Q46624313