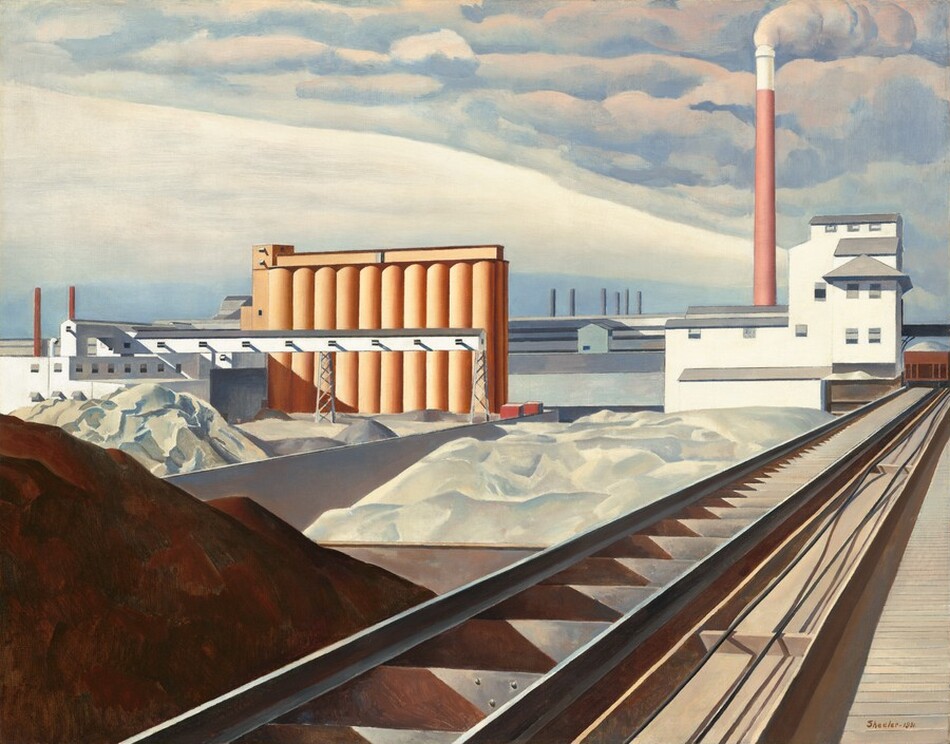

Chester Dale

1922

George Bellows

Painter, American, 1882 - 1925

Hardworking and ambitious, Chester Dale had risen from his modest beginnings on Wall Street at the turn of the century to become a wealthy investment banker and member of the New York Stock Exchange by 1918. In the late teens he and his wife Maud began amassing an outstanding collection of modern American and French paintings as well as a number of works by the Old Masters. After retiring in 1935, Dale served as a trustee of several major art museums, including the National Gallery of Art, of which he became president in 1955. Beginning in 1943, the Gallery received the majority of Dale’s collection, including this portrait by Bellows and three of the artist’s most iconic paintings: Both Members of This Club, Blue Morning, and The Lone Tenement.

Bellows painted this half-length portrait of Dale in his New York studio in January 1922 following three earlier attempts to depict Maud in 1919 (see Maud Murray Dale [Mrs. Chester Dale]). Despite Bellows’s intention to represent Dale as a sportsman at leisure, the portrait possesses a formal, awkward quality. Dale’s tentative expression seems at odds with his reputation as a self-made millionaire and cosmopolite. Some art historians have suggested that Dale was dissatisfied with the image, and that it exemplifies the artist’s difficulty with conventional commissioned portraiture. Nevertheless, Bellows’s portrait of Dale brings to mind the court portraits of King Philip IV of Spain painted by Diego Velázquez, and it is likely that Bellows deliberately quoted this famous Old Master source as an allusion to the fact that both Dale and King Philip were powerful men who collected art on a princely scale.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 113.7 x 88.3 cm (44 3/4 x 34 3/4 in.)

framed: 136.5 x 109.8 cm (53 3/4 x 43 1/4 in.) -

Accession Number

1944.16.1

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Commissioned 1922 by Chester Dale [1883-1962], New York; gift 1944 to NGA.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1924

Paintings and Sculpture by British, American and Canadian Artists; Graphic Art and Photography, Canadian National Exhibiton, Toronto, August-September 1924, no. 205.

Twenty-Third Annual International Exhibition of Paintings, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, April-June 1924, no. 65.

1948

New Yorkers 1848-1968, Portraits, Inc., New York, 1948, no. 6.

1957

George Bellows: A Retrospective Exhibition, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., January-February 1957, no. 54, repro.

Paintings by George Bellows, Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, Ohio, March-April 1957, no. 56.

1965

The Chester Dale Bequest, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1965, unnumbered checklist.

Bibliography

1965

Paintings other than French in the Chester Dale Collection. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 53, repro.

Morgan, Charles H. George Bellows. Painter of America. New York, 1965: 251-252.

1970

American Paintings and Sculpture: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1970: 16, repro.

1971

Braider, Donald. George Bellows and the Ashcan School of Painting. New York, 1971: 131.

1980

Wilmerding, John. American Masterpieces from the National Gallery of Art. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1980: 144, repro.

American Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1980: 26, repro.

1981

Williams, William James. A Heritage of American Paintings from the National Gallery of Art. New York, 1981: repro. 201, 205.

1988

Wilmerding, John. American Masterpieces from the National Gallery of Art. Rev. ed. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1988: 166, repro.

1991

Kopper, Philip. America's National Gallery of Art: A Gift to the Nation. New York, 1991: 238, repro.

1992

American Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1992: 32, repro.

Quick, Michael, Jane Myers, Marianne Doezema, and Franklin Kelly. The Paintings of George Bellows. Exh. cat. Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Columbus (Ohio) Museum of Art; Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, 1992-1993. New York, 1992: 221, fig. 48.

2009

Peck, Glenn C. George Bellows' Catalogue Raisonné. H.V. Allison & Co., 2009. Online resource, URL: http://www.hvallison.com. Accessed 16 August 2016.

Inscriptions

lower right in red: GEO BELLOWS; upper center reverse: PORTRAIT OF CHESTER DALE. / BY GEO BELLOWS, 1922

Wikidata ID

Q20192376