The Bersaglieri

1918

George Luks

Painter, American, 1866 - 1933

Shortly after the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, a series of Liberty Loan drives were organized in major American cities to encourage citizens to help the federal government defray its wartime expenses by purchasing bonds. In New York, elaborate parades were held on the city’s main thoroughfare, Fifth Avenue, which was specially decorated with flags of the Allied forces. Like many American artists, George Luks contributed to the war effort by representing some of these festive occasions.

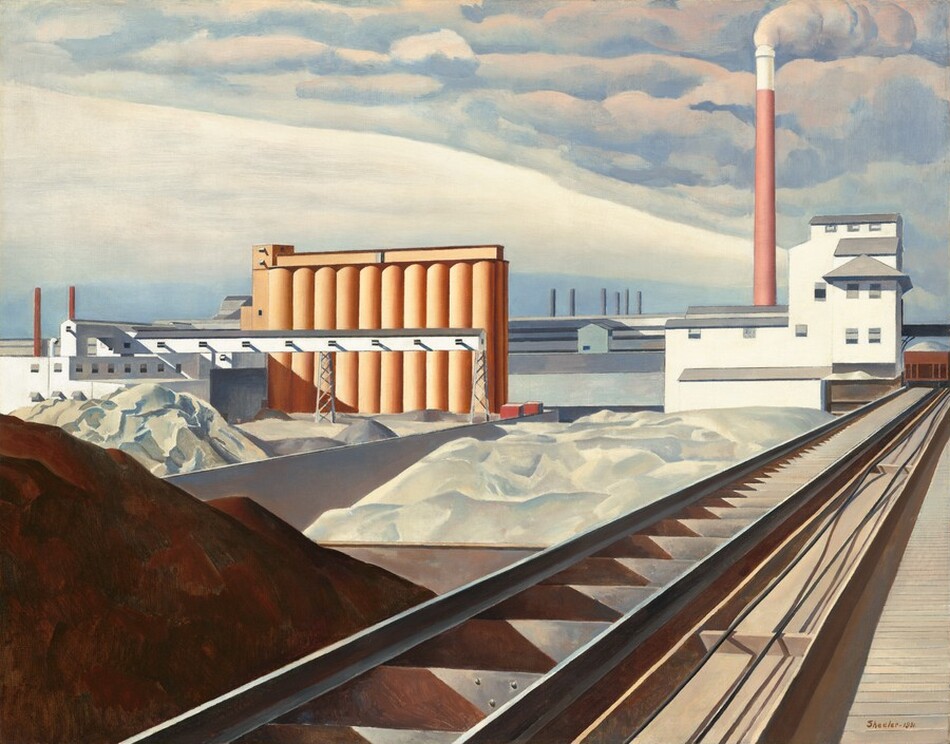

The Bersaglieri shows a regiment of Italian sharpshooters who had been sent to the United States in 1918 to stimulate interest in the fourth Liberty Loan drive. Introduced into the Sardinian army in 1849, they had served heroically in numerous military engagements and were noted for their endurance and ability to march at a speed of four miles an hour. When Italy entered World War I in 1915, 12 regiments of Bersaglieri were in the regular army, and 20 battalions in the mobile militia. On Columbus Day, October 12, 1918, they marched at the head of a procession led by President Woodrow Wilson from East 72nd Street down Fifth Avenue to Washington Square. Luks’s painting successfully conveys the soldiers’ martial prowess, the din of the crowd, and a sense of the excitement generated by the event.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 101.9 x 151.5 cm (40 1/8 x 59 5/8 in.)

framed: 119.1 x 169.6 x 7 cm (46 7/8 x 66 3/4 x 2 3/4 in.) -

Accession Number

1950.5.1

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

The artist; purchased by Arthur F. Egner, South Orange, New Jersey, by 1934;[1] (his estate sale, Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, 4 May 1945, no. 116). (Knoedler and Co., New York), by 1947;[2] purchased 16 May 1950 by NGA.

[1] The painting was lent by Enger to the 1934 exhibition The Work of George Benjamin Luks at the Newark Museum.

[2] The painting was lent by Knoedler to the 1947 exhibition Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition: Paintings by American Artists 1896-1930 at the Syracuse Museum of Fine Arts.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1934

The Works of Benjamin Luks, Newark Museum, New Jersey, 1934-1935, no. 36.

1946

American Painting, Person Hall Art Gallery, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1946, no. 27.

1947

Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition: Paintings by American Artists 1896-1930, Syracuse Museum of Fine Arts, 1947, no. 23.

1949

The Turn of the Century: American Artists 1890-1920, Des Moines Art Center, 1949, unnumbered catalogue.

1954

Extended loan for use by Blair-Lee House, Washington, D.C., 1954-1956.

1973

George Luks: An Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings Dating from 1889 to 1931, Museum of Art, Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, Utica, April-May 1973, no. 47, repro.

The City in American Painting, Allentown Art Museum, Pennsylvania, January-March 1973, unnumbered catalogue, repro.

1988

Extended loan for use by Secretary Frank Carlucci, U.S. Department of Defense, Washington, D.C., 1988-1989.

1991

Extended loan for use by Secretary Lynn Martin, U.S. Department of Labor, Washington, D.C., 1991-1993.

1993

Extended loan for use by Secretary Robert Reich, U.S. Department of Labor, Washington, D.C., 1993-1995.

2001

Extended loan for use by Ambassador William Stamps Farish III, U.S. Embassy residence, London, England, 2001-2002.

Bibliography

1970

American Paintings and Sculpture: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1970: 80, repro.

1980

Wilmerding, John. American Masterpieces from the National Gallery of Art. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1980: no. 52, color repro.

American Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1980: 196, repro.

1981

Williams, William James. A Heritage of American Paintings from the National Gallery of Art. New York, 1981: 207, color repro. 219.

1988

Wilmerding, John. American Masterpieces from the National Gallery of Art. Rev. ed. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1988: 162, no. 58, color repro.

1992

American Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1992: 229, repro.

Inscriptions

lower left: George Luks

Wikidata ID

Q20192161