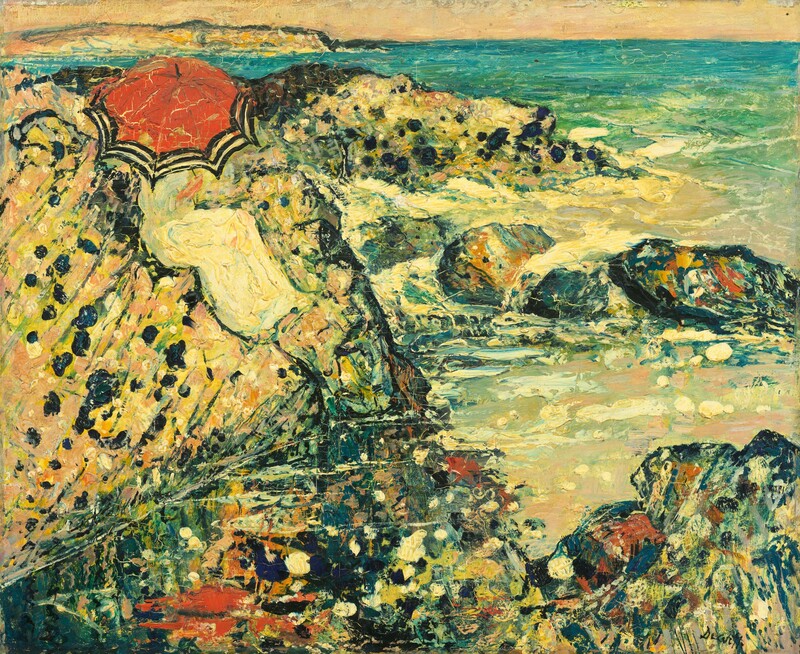

Flecks of Foam

c. 1911/1912

Henry Golden Dearth

Painter, American, 1864 - 1918

When Flecks of Foam was auctioned at the American Art Galleries in 1916 the accompanying catalog described “a low, rambling, rocky coast [that] is brilliant with spots of color—blue, red, yellow, green, black, pink, brown—on a gorgeous summer day, and a woman in white, sheltered under a red parasol, is seated on a rock shelf looking over a sea that all but laps her feet. The spent waves circling among outlying boulders are foam-flecked; farther away are emerald shallows; and the distant sea is blue under a horizon of faint rose.” Henry Golden Dearth was a conventional tonalist painter until around 1912, when, six years before his death at the age of 54, his style underwent a radical transformation. Probably influenced by the late works of the painter Adolphe Monticelli, Dearth began to work outdoors and to apply pigment directly from the tube onto his canvas, sometimes manipulating it with a palette knife or brush handle. Dearth’s most effective works using this unusual technique were his rock pool subjects, among them Flecks of Foam, a highly representative example of the artist’s new direction. Most of these were painted near the artist’s studio in Le Pouldu, a small hamlet in Brittany along France’s northwest coast. One influential critic praised these paintings for a “beauty of workmanship and originality of conception” that earned Dearth a place “among the finest painters of his generation.” Hugo Reisinger, the noted German-born collector and advocate of modern American art, purchased Flecks of Foam in 1912.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on wood

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 45.3 x 55 cm (17 13/16 x 21 5/8 in.)

framed: 62.2 x 72.1 x 5.4 cm (24 1/2 x 28 3/8 x 2 1/8 in.) -

Accession Number

1963.10.120

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

The artist; (M. Knoedler & Co., New York); purchased 1912 by Hugo Reisinger [1856-1914], New York;[1] his estate; (his estate sale, American Art Galleries, New York, 18-20 January 1916, 1st day, no. 5); Edward G. O'Reilly [1870-1934], New York and Bridgeport, Connecticut; (sale, American Art Association, New York, 24-26 January 1917, 2nd day, no. 126); Stephen C. Clark [1882-1960], New York;[2] (sale, American Art Association, New York, 30 November 1928, no. 43); Chester Dale [1883-1962], New York; bequest 1963 to NGA.

[1] The provenance is outlined in the Chester Dale Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington; copy in NGA curatorial files. The Dale Papers record that Reisinger purchased the painting from the April 1912 exhibition of works by Dearth held at Knoedler Galleries. The sale to Reisinger is documented in the M. Knoedler & Co. Records, accession number 2012.M.54, Research Library, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles: Series II; Sales book 10, 1912 February-1916 April, page 24; copy in NGA curatorial files. It is not yet clear whether Knoedler had the painting on consignment from the artist or had already purchased it from the artist.

[2] The copy of the sale catalogue in the NGA Library is annotated "W.W. Seaman - agt. 325". Seaman must have been buying for Clark.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1912

Paintings by Henry Golden Dearth, M. Knoedler & Co., New York, 1912, no. 11.

1937

An Exhibition of American Paintings from the Chester Dale Collection, The Union League Club, New York, 1937, no. 43.

1943

Paintings from the Chester Dale Collection, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1943-1951, unnumbered catalogue, repro.

Bibliography

1943

Paintings from the Chester Dale Collection. Philadelphia, 1943: unpaginated, repro.

1965

Paintings other than French in the Chester Dale Collection. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 44, repro.

1970

American Paintings and Sculpture: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1970: 48, repro.

1980

American Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1980: 142, repro.

1992

American Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1992: 157, repro.

Inscriptions

lower right: Dearth

Wikidata ID

Q20191538