Still Life with Dead Game

1661

Willem van Aelst

Artist, Dutch, 1627 - 1683

Still lifes with hunting motifs became popular in Dutch art in the latter part of the seventeenth century, at a time when Dutch society grew wealthier and more refined. Willem van Aelst, who worked in Paris and Florence before settling in Amsterdam, was one of the first still-life painters to depict hunting trophies. Many such paintings create a heightened sense of reality by featuring full-scale representations of the objects they portray, as in the life-sized animals here. This kill includes a white rooster, a wild hare, a partridge, and several songbirds. Another large bird, possibly a black rooster, is partially hidden and cannot be identified because the canvas has been cropped, which has eliminated its head. Two red velvet hoods used in falconry dangle from a cord. The fly, attracted to the blood on the rooster's comb, may be the only sign of life, but it is also a harbinger of the decay that follows death. Van Aelst’s superb skill in rendering the illusion of fur, feathers, and flesh set a major precedent for later French, British, and American painters of sporting scenes.

The relief depicting the story of Diana and Actaeon, carved on the stone ledge, is evidence that Van Aelst's painting was intended to represent the general theme of the hunt rather than the spoils of a specific outing. Diana, the chaste goddess of the hunt, splashes water on Actaeon, a mortal huntsman who surprised her at her bath. In punishment for having embarrassed Diana, Actaeon sprouts the antlers of a stag and will be killed by his own hounds.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 50

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 84.7 x 67.3 cm (33 3/8 x 26 1/2 in.)

-

Accession Number

1982.36.1

More About this Artwork

Article: Making Pictures of the Animals We Eat

When Dutch artist Willem van Aelst painted dead animals, did he use the images to grapple with the full circle of life?

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Probably (sale, Amsterdam, 14 October 1749, no. 16).[1] Dr. C.J.K. van Aalst, Huis-te-Hoevelaken, by 1939;[2] (sale, Sotheby Mak van Waay, Amsterdam, 18 May 1981, no. 1); (Richard Green, London); sold 8 June 1982 to NGA.

[1] This sale was kindly brought to the attention of Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. by Tanya Paul; see her letter of 30 October 2007, in NGA curatorial files. The sale consisted of works from the collections of Johan Diedrick Pompe van Meerdervoort, Burgemeester of Dordrecht, and the painter Jan van Huysum (1682–1749), although the consignor of individual lots is not specified. The work is described as “Een doode Haan en Haas en verder bywerk, kunstig geschilderd door van Aalst, h 2v. 7 en een half d., br. 2 v. 3 d., in een zwarte Lyst met een verguld binnen Lysje. 18-10,” and Paul writes that the NGA painting is the only Van Aelst to her knowledge that depicts both a rooster and a hare. See Gerard Hoet, Catalogus van schilderyen, reprint, Soest, 1976: 268–269.

[2] [2] J.W. von Moltke, ed. Dutch and Flemish Old Masters in the Collection of Dr. C.J.K. van Aalst. Huis-te-Hoevelaken, Holland, foreword by W.R. Valentiner, Verona, 1939: 50, pl. 11.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1997

Rembrandt and the Golden Age: Dutch Paintings from the National Gallery of Art, The Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia, 1997, unnumbered brochure.

2002

Deceptions and Illusions: Five Centuries of Trompe L'Oeil Painting, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2002-2003, not in catalogue.

2012

Elegance and Refinement: The Still Life Paintings of Willem van Aelst, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Ntaional Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2012, no. 15, repro.

Bibliography

1939

Moltke, Joachim Wolfgang, ed. Dutch and Flemish old masters in the collection of Dr. C.J.K. van Aalst, Huis-te-Hoevelaken, Holland. Foreword by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Translated. Verona, 1939: 50, pl. 11.

1984

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 306, no. 405, color repro.

Sullivan, Scott A. The Dutch Gamepiece. Montclair, New Jersey, 1984: 91 n. 32.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 17, repro.

1988

Grimm, Claus. Stilleben: die niederländischen und deutschen Meister. Stuttgart, 1988: 172, repros. 115-117.

1992

National Gallery of Art. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1992: 134, repro.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 3-4, color repro. 2.

Barolsky, Paul. "Still Life and Metamorphosis." _Source: Notes in the History of Art _ 14, no. 2 (1995): 36, repro.

1999

Chong, Alan, and Wouter Th. Kloek. Still-life Paintings from the Netherlands, 1550-1720. Exh. cat. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; Cleveland Museum of Art. Zwolle, 1999: 244, fig. 61a.

2008

Paul, Tanya. "'Beschildert met een Glans': Willem van Aelst and artistic self-consciousness in seventeenth-century Dutch still life painting." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, 2008: x, 130, 245, 282, 379, fig. 50.

2012

Paul, Tanya, et al. Elegance and Refinement: The still-life paintings of Willem van Aelst. Exh. cat. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 2012: 130-133, no. 15, repro.

Inscriptions

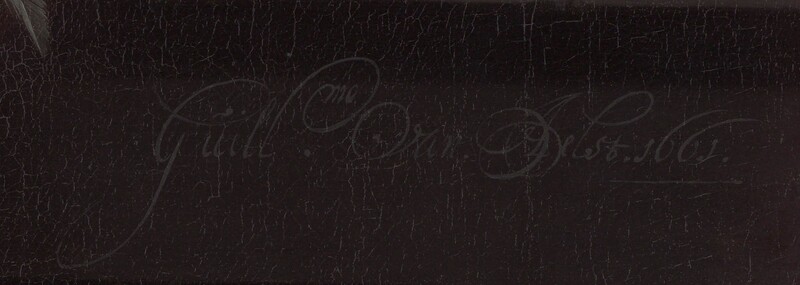

lower right below table top: Guill.mo van. Aelst. 1661.

Wikidata ID

Q20177577