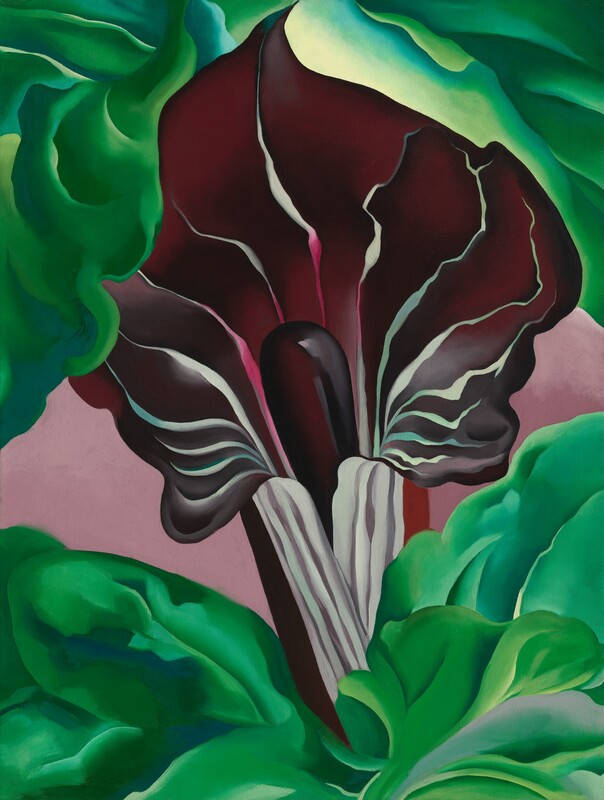

Jack-in-Pulpit - No. 2

1930

Georgia O'Keeffe

Painter, American, 1887 - 1986

In her youth, Georgia O’Keeffe had been particularly fascinated by the jack-in-the-pulpit. In 1930, she executed a series of six paintings of the common North American herbaceous flowering plant at Lake George in New York. The National Gallery of Art is home to five of these six works: this one, Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. 3, Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV, Jack-in-the-Pulpit Abstraction – No. 5, and Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. VI. In this particular work, the plant is set against a pale mauve background, and all four corners of the composition are occupied by green foliage.

The large, magnified representations of flowers that O’Keeffe embarked upon in the 1920s became her most famous subjects. Although such images had antecedents in the photographs of Paul Strand and Edward Steichen and were to some extent paralleled in the paintings of Charles Demuth, O’Keeffe rendered them at an unprecedented scale. She ultimately became more closely associated with flower imagery than her male peers.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 101.6 × 76.2 cm (40 × 30 in.)

framed: 127.32 × 101.92 × 9.53 cm (50 1/8 × 40 1/8 × 3 3/4 in.) -

Accession Number

1987.58.1

-

Copyright

© Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

The artist [1887-1986]; her estate; bequest 1987 to NGA.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1931

Georgia O'Keeffe, An American Place, New York, 1931, one of nos. 7-11.

1932

Possibly Twenty-Seventh Annual Exhibition of Paintings by American Artists, City Art Museum, St. Louis, August-October 1932, no. 37 (this may also be NGA 1987.58.2).

Possibly Exhibition of The American Society of Painters, Sculptors and Gravers, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, February 1932, no. 105, as Jack-in-the-Pulpit.

1943

Georgia O'Keeffe, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1943, no. 37, repro.

1953

Possibly An Exhibition of Paintings by Georgia O'Keeffe, Dallas Museum of Fine Arts; The Mayo Hill Galleries, Delray Beach, Florida, 1953, no. 13, as Jack in the Pulpit.

1970

Georgia O'Keeffe Retrospective Exhibition, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; The Art Institute of Chicago; San Francisco Museum of Art, 1970-1971, no. 66, repro.

1984

Reflections of Nature: Flowers in American Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1984, unnumbered catalogue, frontispiece, fig. 56.

2009

Dove/O'Keeffe: Circles of Influence, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, 2009, pl. 56.

Georgia O'Keeffe: Abstraction, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.; Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, 2009-2010, unnumbered catalogue, pl. 118.

2011

25th Year Anniversary Exhibition, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, 2011-2013, no catalogue.

2013

Modern Nature: Georgia O'Keeffe and Lake George, The Hyde Collection Art Museum, Glens Falls; Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, de Young Museum, 2013-2014, no. 51, repro.

2015

Collection Conversations: The Chrysler and the National Gallery, Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, 2015-2016, no catalogue.

2016

O'Keeffe, Stettheimer, Torr, Zorach: Women Modernists in New York, Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach; Portland (Maine) Museum of Art, 2016, no. 59, fig. 8.

Bibliography

1976

O’Keeffe, Georgia. Georgia O’Keeffe. New York, 1976: color pl. 39.

1984

Hoffman, Katherine. An Enduring Spirit: The Art of Georgia O’Keeffe. Metuchen, NJ, 1984: 104.

1992

American Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1992: 250, repro.

1995

Benke, Britta. Georgia O’Keeffe 1887-1986: Flowers in the Desert. Cologne, 1995: 42, color repro.

1996

Wagner, Anne Middleton. Three Artists (Three Women): Modernism and the Art of Hesse, Krasner, and O’Keeffe. Berkeley, 1996: 70-72, color pl. 9.

1999

Lynes, Barbara Buhler. Georgia O'Keeffe: Catalogue Raisonné. 2 vols. New Haven and London, 1999: 1:433, no. 716, color repro.

2004

Eldredge, Charles C. “Skunk Cabbages, Seasons and Cycles.” In Joseph S. Czestochowski, ed., Georgia O’Keeffe: Vision of the Sublime. Memphis, 2004: 71-72, pl. 41.

2016

Roberts, Ellen E. O'Keeffe, Stettheimer, Torr, Zorach: Women Modernists in New York. Exh. cat. Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach; Portland (Maine) Museum of Art. West Palm Beach, 2016: 123 fig. 8, 127-128, 150 no. 59.

Inscriptions

upper left reverse: Jack in Pulpit-No 2-30 / signed within five-pointed star: OK

Wikidata ID

Q20192831