Self-Portrait

1659

Rembrandt van Rijn

Artist, Dutch, 1606 - 1669

The man’s surroundings are blurred, but his illuminated face is finely detailed. The sad eyes fix on us intently. What is he trying to communicate? We know he is Rembrandt van Rijn, a Dutch painter of extraordinary fame today, but he seems unsettled. His brows are knitted, his cheeks are sunken, and deep wrinkles gather at his forehead and eyes. Painted when the artist was 53 years old, this penetrating work was made after Rembrandt was forced to sell his possessions to pay off creditors. They could not take away his skill or dignity, which he displays in this self-portrait.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 48

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 84.5 x 66 cm (33 1/4 x 26 in.)

framed: 122.9 x 104.1 x 8.9 cm (48 3/8 x 41 x 3 1/2 in.) -

Accession Number

1937.1.72

More About this Artwork

Article: Artists Who Inspired Mark Rothko

Learn about some of the artists the modern painter was in dialogue with throughout his career.

Video: Rembrandt's "Self-Portrait" (ASL)

This video provides an ASL description of Rembrandt's Self-Portrait.

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Purchased by George Brudenell, 4th earl of Cardigan [1712-1790, later George Montagu, duke of Montagu (new creation)], Montagu House, Whitehall, London, by 1767;[1] by inheritance to his daughter and sole heiress, Elizabeth, duchess of Buccleuch [1743-1827, née Lady Elizabeth Montagu, wife of Henry Scott, 3rd duke of Buccleuch and 5th duke of Queensberry, 1746-1812], Montagu House; by descent through the dukes of Buccleuch and Queensberry to John Charles Montagu, 7th duke of Buccleuch and 9th duke of Queensberry [1864-1935], Montagu House; sold 1928 to (P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., New York), on joint account with (M. Knoedler & Co., New York);[2] sold January 1929 to Andrew W. Mellon, Pittsburgh and Washington, D.C.; deeded 28 December 1934 to The A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, Pittsburgh; gift 1937 to NGA.

[1] The Knoedler prospectus for the painting (in NGA curatorial files) states that the painting was purchased by Brudunell in 1740. However, the first firm evidence for his ownership is a mezzotint after the self-portrait, dated 1767 and published by R. Earlom (1743-1822), which is inscribed as "From the Original Picture...In the Collection of his Grace the Duke of Montagu" (see John Charrington, A Catalogue of the Mezzotints After, or Said to Be After, Rembrandt, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1923: 34-35, no. 49. According to an inventory of Montagu House, Whitehall, made in 1770, this painting and Rembrandt's An Old Woman Reading (still at the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry's Drumlanrig Castle in Dumfriesshire, Scotland) were purchased together for 140 pounds; see Francis Russell's entry on An Old Woman Reading in Gervase Jackson-Stops, ed., The Treasure Houses of Britain: Five Hundred Years of Private Patronage and Art Collecting, exh. cat., National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., New Haven and London, 1985: 363-364, no. 292. See also Burton B. Fredericksen, "Leonardo and Mantegna in the Buccleuch Collection," The Burlington Magazine 133 (February 1991): 116.

[2] Nicholas H.J. Hall, ed., Colnaghi in America: A Survey to Commemorate the First Decade of Colnaghi New York, New York, 1992: 24, fig. 24. According to the Getty Provenance Index® Database of Public Collections (J. Paul Getty Trust, Paintings Record 17095), there is no regular entry in Colnaghi’s stockbooks, but transactions for the painting are documented in Colnaghi's Private Ledger; the painting was Knoedler’s number A-409. The 1928 sale of the painting by the 7th duke is also confirmed by a letter of 28 November 1928, from Charles J. Holmes, then director of the National Gallery, London, to Otto Gutekunst of Colnaghi (in NGA curatorial files, received at the time of the 1937 gift). Gutekunst had shown Holmes the painting "in confidence" and Holmes wrote to ask if it could be lent briefly to the Gallery "before it crosses the Atlantic."

Associated Names

- Montagu, duke of Montagu (new creation) and 4th earl of Cardigan, George Brudenell

- Buccleuch, Elizabeth, duchess of

- Scott, 7th duke of Buccleuch and 9th duke of Queensberry, John Charles Montagu Douglas

- P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., Ltd.

- M. Knoedler & Company

- Mellon, Andrew W.

- The A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust

Exhibition History

1872

Exhibition of the Works of the Old Masters. Winter Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1872, no. 181.

1898

Rembrandt. Collection des oeuvres des maîtres réunies, à l'occasion de l'inauguration de S. M. la Reine Wilhelmine, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1898, no. 102.

1899

Exhibition of Works by Rembrandt. Winter Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1899, no. 6.

1930

The Thirteenth Loan Exhibition of Old Masters: Paintings by Rembrandt, The Detroit Institute of Arts, May 1930, no. 62.

A Loan Exhibition of Sixteen Masterpieces, Knoedler Galleries, New York, January 1930, no. 8.

1935

Loan Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings and Etchings by Rembrandt and His Circle, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1935-1936, no. 6.

Rembrandt Tentoonstelling, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1935, no. 26.

1939

Masterpieces of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture from 1300-1800, New York World's Fair, 1939, no. 307.

1969

Rembrandt in the National Gallery of Art [Commemorating the Tercentenary of the Artist's Death], National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1969, no. 19, repro.

1989

Masterpieces of Western European Painting of the XVIth-XXth Centuries from the Museums of the European Countries and USA, State Hermitage Museum, Leningrad, 1989, no. 13, repro.

1992

Dutch Art and Scotland: A Reflection of Taste, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, 1992, no. 53, repro.

1996

Rembrandt: His Pupils and Followers, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, 1996, unnumbered brochure, repro.

1999

Rembrandt By Himself, The National Gallery, London; Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis, The Hague, 1999-2000, no. 73, repro.

2002

Rembrandt: Dipinti, incisioni e riflessi sul '600 e '700 italiano, Scuderie del Quirinale, Rome, 2002-2003, no. 6D, repro. on title page.

2009

Rembrandt's People, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, 2009-2010, brochure no. 3, repro. and cover.

2011

Rembrandt in America, North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh; Cleveland Museum of Art; Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2011-2012, no. 34, pl. 9.

2014

Rembrandt: The Late Works, National Gallery, London; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2014-2015, no. 2, repro.

Bibliography

1770

Manuscript list of pictures at Montagu House, Whitehall. Boughton House, Northamptonshire, 1770: unpaginated.

1829

Smith, John. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters. 9 vols. London, 1829-1842: 7(1836): 88, no. 215.

1868

Vosmaer, Carel. Rembrandt Harmens van Rijn, sa vie et ses œuvres. The Hague, 1868: 493.

1872

Royal Academy of Arts. Exhibition of Old Masters and by Deceased Masters of the British School. Exh. cat. Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1872: no. 181.

1877

Vosmaer, Carel. Rembrandt Harmens van Rijn: sa vie et ses oeuvres. 2nd ed. The Hague, 1877: 358, 560.

1883

Bode, Wilhelm von. Studien zur Geschichte der holländischen Malerei. Braunschweig, 1883: 542, 585, no. 197.

1885

Dutuit, Eugène. Tableaux et dessins de Rembrandt: catalogue historique et descriptif; supplément à l'Oeuvre complet de Rembrandt. Paris, 1885: no. 43, 61, 70, no. 165.

1886

Wurzbach, Alfred von. Rembrandtgalerie. Stuttgart, 1886: no. 160.

1887

Champlin, John Denison, Jr., and Charles C. Perkins, eds. Cyclopedia of painters and paintings. 4 vols. New York, 1887: 4:24.

1893

Michel, Émile. Rembrandt: Sa vie, son oeuvre et son temps. Paris, 1893: 557.

1894

Michel, Émile. Rembrandt: His Life, His Work, and His Time. 2 vols. Translated by Florence Simmonds. New York, 1894: 2:235.

1897

Bode, Wilhelm von, and Cornelis Hofstede de Groot. The Complete Work of Rembrandt. 8 vols. Translated by Florence Simmonds. Paris, 1897-1906: 6:3-14, no. 431, repro.

Moes, Ernst Wilhelm. Iconographia Batava. 2 vols. Amsterdam, 1897-1905: 2(1905):315, no. 60.

1898

Michel, Émile. "L’Exposition Rembrandt à Amsterdam." Gazette des Beaux-Arts 20 (1898): 467-480.

McKay, Andrew. Catalogue of the pictures in Montagu House, belonging to the Duke of Buccleuch. London, 1898: 5, no. 12.

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. De Rembrandt tentoonstelling te Amsterdam: 40 photogravures met tekst. Exh. cat. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1898: no. 33, repro.

Hofstede de Groot, Comelis. Rembrandt: Collection des oeuvres du maître réunies, à l’occasion de l’inauguration de S. M. la Reine Wilhelmine. Exh. cat. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1898: no. 102.

1899

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. Rembrandt. 26 Photogravures naar de beste schilderijen der tentoonstellingen te London en Amsterdam. Amsterdam, 1899: no. 33, repro.

Bell, Malcolm. Rembrandt van Rijn and His Work. London, 1899: 83-84, 145.

Royal Academy of Arts. Exhibition of works by Rembrandt. Exh. cat. Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1899: 10, no. 6.

1902

Neumann, Carl. Rembrandt. Berlin, 1902: 488.

1904

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt: des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. Stuttgart, 1904: 217, 267, repro.

1906

Veth, Jan. Rembrandt's Leven en Kunst. Amsterdam, 1906: 161-162.

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt, des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, 1906: repro. 343, 404.

Wurzbach, Alfred von. Niederlandisches Kunstler-Lexikon. 3 vols. Vienna, 1906-1911: 2(1910):402.

1907

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. 8 vols. Translated by Edward G. Hawke. London, 1907-1927: 6(1916):273-274, no. 554.

Bell, Malcolm. Rembrandt van Rijn. The great masters in painting and sculpture. London, 1907: 79, 126.

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt, reproduced in over five hundred illustrations. Classics in Art 2. New York, 1907: 343, repro.

1908

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt, des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. 3rd ed. Stuttgart and Berlin, 1908: repro. 403, 562.

1909

Knackfuss, Hermann. Rembrandt. Künstler-Monographien. Bielefeld, 1909: 158-159, pl. 164.

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt: Des Meisters Gemälde. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. Stuttgart and Leipzig, 1909: repro. 403, 562.

1913

Graves, Algernon. A Century of Loan Exhibitions, 1813-1912. 5 vols. London, 1913-1915: 3(1914):1010.

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt, reproduced in over five hundred illustrations. Classics in Art 2. 2nd ed. New York, 1913: repro. 403.

1921

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Rembrandt: wiedergefundene Gemälde (1910-1920). Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben. 27. Stuttgart and Berlin, 1921: 403, repro.

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Classics in Art 2. 3rd ed. New York, 1921: 403, repro.

1922

Neumann, Carl. Rembrandt. 2 vols. Revised ed. Munich, 1922: 2:540, 542.

1923

Meldrum, David S. Rembrandt’s Painting, with an Essay on His Life and Work. New York, 1923: 137, 199, pl. 339.

1924

Knackfuss, Hermann. Rembrandt. Künstler-Monographien. Leipzig, 1924: 162, pl. 170.

1929

Rutter, Frank. "Notes from Abroad." International Studio 92 (1929): 64-67, repro.

1930

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. The thirteenth loan exhibition of old masters, paintings by Rembrandt. Exh. cat. Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, 1930: no. 62.

1931

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Rembrandt Paintings in America. New York, 1931: no. 141, repro.

1932

Rijckevorsel, J. L. A. A. M. van. "Rembrandt en de Traditie." Ph.D. dissertation, Rijksuniversiteit Nijmegen, 1932: 150.

1935

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt Schilderijen, 630 Afbeeldingen. Utrecht, 1935: no. 51, repro.

Schmidt-Degener, Frederik. Rembrandt Tentoonstelling. Exh. cat. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1935: 58, no. 26, repro.

Rich, Daniel Catton. Loan exhibition of paintings, drawings and etchings by Rembrandt and his circle. Exh. cat. Art Institute of Chicago, 1935: 18, 65, no. 6, repro.

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt Gemälde, 630 Abbildungen. Vienna, 1935: no. 51, repro..

1936

Bredius, Abraham. The Paintings of Rembrandt. New York, 1936: no. 51, repro.

1937

Jewell, Edward Alden. "Mellon's Gift." Magazine of Art 30, no. 2 (February 1937): 82.

Cortissoz, Royal. An Introduction to the Mellon Collection. Boston, 1937: 39.

1939

McCall, George Henry. Masterpieces of art: Catalogue of European paintings and sculpture from 1300-1800. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Exh. cat. New York World's Fair, New York, 1939: 149-150, no. 307.

1941

National Gallery of Art. Preliminary Catalogue of Paintings and Sculpture. Washington, 1941: 164, no. 72.

1942

Borenius, Tancred. Rembrandt: Selected Paintings. London and New York, 1942: 35, no. 81, repro.

National Gallery of Art. Book of illustrations. 2nd ed. Washington, 1942: 72, repro. 29, 240.

Bredius, Abraham. The Paintings of Rembrandt. 2 vols. Translated by John Byam Shaw. Oxford, 1942: 1:5, no. 51, repro.

1943

Benesch, Otto. "The Rembrandt Paintings in the National Gallery of Art." The Art Quarterly 6, no. 1 (Winter 1943): 28, 30 fig. 11.

1944

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds. Masterpieces of Painting from the National Gallery of Art. Translated. New York, 1944: 98, color repro.

1946

National Gallery of Art. Favorite paintings from the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. New York, 1946: 47-49, color repro.

1948

Rosenberg, Jakob. Rembrandt. 2 vols. Cambridge, MA, 1948: 1:30-31, color frontispiece.

1949

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Mellon Collection. Washington, 1949 (reprinted 1953 and 1958): 87, repro.

1956

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1956: 42, repro.

1957

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Comparisons in art: A Companion to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. London, 1957: pl. 78.

1960

Roger-Marx, Claude. Rembrandt. Translated by W.J. Strachan and Peter Simmons. New York, 1960: 13, repro., 64, 96.

Baird, Thomas P. Dutch Painting in the National Gallery of Art. Ten Schools of Painting in the National Gallery of Art 7. Washington, D.C., 1960: 8, 14-15, color repro.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963 (reprinted 1964 in French, German, and Spanish): 184, no. 72, repro.

1964

Rosenberg, Jakob. Rembrandt: Life and Work. Revised ed. Greenwich, Connecticut, 1964: 47.

1965

National Gallery of Art. Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. Washington, 1965: 109.

1966

Rosenberg, Jakob, Seymour Slive, and Engelbert H. ter Kuile. Dutch Art and Architecture: 1600–1800. Pelican History of Art. Baltimore, 1966: 71-72, pl. 50.

Bauch, Kurt. Rembrandt Gemälde. Berlin, 1966: 17, no. 330, repro.

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds. A Pageant of Painting from the National Gallery of Art. 2 vols. New York, 1966: 1: 232, color repro.

1967

Erpel, Fritz. Die Selbstbildnisse Rembrandts. Berlin, 1967: 46, 184, pl. 56.

1968

Gerson, Horst. Rembrandt Paintings. Amsterdam, 1968: 443, no. 736, repro., 503.

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 97, repro.

Gandolfo, Giampaolo et al. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Great Museums of the World. New York, 1968: 135-136, color repro.

1969

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt: The Complete Edition of the Paintings. Revised by Horst Gerson. 3rd ed. London, 1969: repro. 47, 551, no. 51.

National Gallery of Art. Rembrandt in the National Gallery of Art: Commemorating the tercentenary of the artist's death. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1969: 7, 29, no. 19, repro.

1972

Roberts, Keith. "Current and Forthcoming Exhibitions: London." The Burlington Magazine 114, no. 830 (May 1972): 353.

1975

Wright, Christopher. Rembrandt and His Art. London and New York, 1975: 98-99, pl. 80.

National Gallery of Art. European paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. Washington, 1975: 284, repro.

1977

Bolten, J., and H. Bolten-Rempt. The Hidden Rembrandt. Translated by Danielle Adkinson. Milan and Chicago, 1977: 199, no. 486, repro.

1978

Clark, Kenneth. An Introduction to Rembrandt. London, 1978: 30-31, fig. 26.

1979

Watson, Ross. The National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1979: 69, pl. 54.

1982

Wright, Christopher. Rembrandt: Self-Portraits. New York, 1982: 32, color pl. 88.

1984

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 270, no. 351, color repro.

Schwartz, Gary. Rembrandt: Zijn leven, zijn schilderijen. Maarssen, 1984: 352, no. 417, repro.

Rosenberg, Jakob, Seymour Slive, and Engelbert H. ter Kuile. Dutch Art and Architecture. The Pelican History of Art. Revised ed. Harmondsworth, 1984: 71-72, pl. 50.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 328, repro.

Pelfrey, Robert H., and Mary Hall-Pelfrey. Art and Mass Media. New York, 1985: 97, repro.

Schwartz, Gary. Rembrandt: His Life, His Paintings. New York, 1985: 352, no. 417, repro.

Jackson-Stops, Gervase. The Treasure Houses of Britain: Five Hundred Years of Private Patronage and Art Collecting. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New Haven, 1985: 363-364, no. 292.

1986

Sutton, Peter C. A Guide to Dutch Art in America. Washington and Grand Rapids, 1986: 314, repro.

Tümpel, Christian. Rembrandt. Translated by Jacques and Jean Duvernet, Léon Karlson, and Patrick Grilli. Paris, 1986: 368-369, color repro., 427, no. A72.

Guillaud, Jacqueline, and Maurice Guillaud. Rembrandt: das Bild des Menschen. Translated by Renate Renner. Stuttgart, 1986: no. 739, color repro.

Guillaud, Jacqueline, and Maurice Guillaud. Rembrandt, the human form and spirit. Translated by Suzanne Boorsch et al. New York, 1986: no. 739, color repro.

1989

Obnovlenskaia, N.G. Masterpieces of western European painting of the XVIth-XXth centuries from the museums of the European countries and USA. Exh. cat. State Hermitage Museum, Leningrad, 1989: no. 13, repro.

1991

Kopper, Philip. America's National Gallery of Art: A Gift to the Nation. New York, 1991: 21, color repro.

Martz, Louis L. From Renaissance to Baroque: essays on literature and art. Columbia, Missouri, 1991: 242-245, fig. 39.

Fredericksen, Burton B. "Leonardo and Mantegna in the Buccleuch Collection." The Burlington Magazine 133, no. 1055 (February 1991): 116.

1992

Lloyd Williams, Julia. Dutch Art and Scotland: A Reflection of Taste. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, 1992: no. 53, color repro.

Fiero, Gloria K. The Age of the Baroque and the European Enlightenment. The Humanist Tradition 4. 1st ed. [7th ed. 2015] Dubuque, Iowa, 1992: 51, fig. 22.13.

Schneider, Norbert. Porträtmalerei: Hauptwerke europäischer Bildniskunst 1420-1670. Cologne, 1992: 115-116, repro.

1994

Jackson, Jed. Art: a comparative study. Dubuque, Iowa, 1994: 166-167, fig. 123.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 261-265, color repro. 263.

Stokstad, Marilyn. Art History. New York, 1995: 792, fig.19-50.

Slive, Seymour, and Jakob Rosenberg. Dutch painting 1600-1800. Pelican History of Art. Revised and expanded ed. New Haven, 1995: 85, 86, repro.

Denker, Eric. In Pursuit of the Butterfly: Portraits of James McNeill Whistler. Exh. cat. National Portrait Gallery, Washington. Seattle, 1995: 59, 60, 61, repro.

Genet, Jean. Rembrandt: le secret de Rembrandt, suivi de Ce qui est resté d'un Rembrandt déchiré en petits carrés bien réguliers, et foutu aux chiottes. Paris, 1995: 94, repro.

1996

Tansey, Richard G. and Fred S. Kleiner. Gardner's Art Through the Ages. 10th ed. Fort Worth, 1996: 859, color fig. 24.50.

Pelfrey, Robert H. Art and mass media. New York, 1985. Reprint, Dubuque, Iowa, 1996: 94-95, fig. 4.10.

Kissick, John. Art: Context and Criticism. Madison, 1996: 266, repro.

1997

Fleischer, Roland E., and Susan C. Scott, eds. Rembrandt, Rubens, and the art of their time: recent perspectives. Papers in art history from the Pennsylvania State University 11. University Park, PA, 1997: no. 1-5, repro.

Dworetzky, John P., Psychology, 1997, no. 452-453, repro.

1998

Fiero, Gloria K. Faith, Reason and Power in the Early Modern World. The Humanistic Tradition 4. 3rd ed. New York, 1998: 54, fig. 22.13.

1999

White, Christopher, and Quentin Buvelot. Rembrandt by Himself. Exh. cat. National Gallery, London; Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis, The Hague. New Haven, 1999: 200-203, no. 73, repro.; X-radiograph, fig. 73a; detail, fig. 73b.

2001

Wetering, Ernst van de, and Bernhard Schnackenburg. The Mystery of the Young Rembrandt. Exh. cat. Staatliche Museen Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Schloss Wilhelmshöhe; Museum het Rembrandthuis, Amsterdam. Wolfratshausen, 2001: 115-116, fig. 29.

2002

Hinterding, Erik. Rembrandt: dipinti, incisioni e riflessi sul '600 e '700 italiano. Exh. cat. Scuderie Papali al Quirinale, Rome; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Milan, 2002: 388-389, no. 6D, repro. on title page.

2003

Ackley, Clifford S., et al. Rembrandt's journey: painter, draughtsman, etcher. Exh. cat. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Art Institute of Chicago. Boston, 2003: 308-309, no. 215, repro.

2004

Hand, John Oliver. National Gallery of Art: Master Paintings from the Collection. Washington and New York, 2004: 198-199, no. 156, color repro.

2005

Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project. A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings. Vol. 4: The Self-Portraits. Edited by Ernst van de Wetering. Dordrecht, 2005: 94, 95 fig. 17, 96, 109, 110, 111, 115 fig. 54, 116, 129, 151, 189, 216, 244, 281, 282 fig. 289, 382, 474, 484, 492, 496, 498-507, 584, 601.

2006

Rønberg, Lene Bøgh, and Eva de la Fuente Pedersen. Rembrandt?: The Master and His Workshop. Exh. cat. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, 2006: 45, fig. 8.

2009

Zafran, Eric. Rembrandt's People. Exhibition brochure. Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, 2009: no. 3, 10-11, repro.

2011

Keyes, George S., Tom Rassieur, and Dennis P. Weller. Rembrandt in America: collecting and connoisseurship. Exh. cat. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh; Cleveland Museum of Art; Minneapolis Institute of Arts. New York, 2011: no. 34, pl. 9, 54-55, 134, 191.

2014

Clark, T.J. "World of Faces," review of Rembrandt: The Late Works, National Gallery London, 2014-2015, London Review of Books 36, no. 23 (4 December 2014): 16, 17, color repro.

Bikker, Jonathan, and Gregor J.M. Weber. Rembrandt: The Late Works. Exh. cat. National Gallery, London; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. London, 2014: no. 2, 46, repro. (detail) 46, repro. 47, 297.

Wieseman, M.E., Jonathan Bikker, et al. Rembrandt: The Late Works, Supplement with Provenance, Selected Literature and Bibliography. Online supplement to Exh. cat. National Gallery London; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. London, 2014, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/media/25834/rembrandt-supplement.pdf: 6, 12-13.

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. NGA Online Editions, http://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/17th-century-dutch-paintings.

2016

Warner-Johnson, Tim, and Jeremy Howard, eds. Colnaghi: Past, Present and Future: An Anthology. London, 2016: 112-113, color plate 33.

2018

Seifert, Christian Tico, et al. Rembrandt: Britain's Discovery of the Master. Exh. cat. National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2018: 123 fig. 141.

2022

Gifford, E. Melanie. "Rembrandt and the Rembrandtesque: The Experience of Artistic Process and Its Imitation." In Tributes to Maryan W. Ainsworth, Collaborative Spirit: Essays on Northern European Art, 1350-1650. Edited by Anna Koopstra, Christine Seidel and Joshua P. Waterman. London/Turnhout, 2022: 338-339, color fig. 6b.

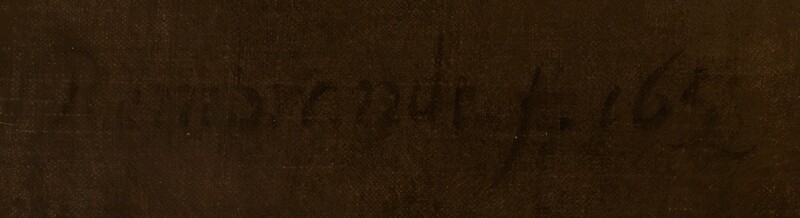

Inscriptions

center left: Rembrandt f. 1659

Wikidata ID

Q2872723