A Woman Holding a Pink

1656

Rembrandt van Rijn

Artist, Dutch, 1606 - 1669

After learning the fundamentals of drawing and painting in his native Leiden, Rembrandt van Rijn went to Amsterdam in 1624 to study for six months with Pieter Lastman (1583–1633), a famous history painter. Upon completion of his training Rembrandt returned to Leiden. Around 1632 he moved to Amsterdam, quickly establishing himself as the town’s leading artist, specializing in history paintings and portraiture. He received many commissions and attracted a number of students who came to learn his method of painting.

The simplicity of concept, forcefulness of execution, and nobility of character evident in A Woman Holding a Pink are qualities that have consistently garnered admiration for this work. The pink carnation held by the woman has long been associated with the sacrament of marriage, and it often symbolizes either marriage or betrothal. In a second association, the carnation, called nagelbloem (nail flower) in Dutch, is also associated with the Crucifixion of Christ. In family portraits, the carnation thus alludes to the fact that true conjugal love finds its inspiration in the divine love epitomized by Christ's Passion. In this particular work, the carnation furthermore relates to the still life on the tabletop: the book with brass clasps is probably a Bible, and the apples symbolize the legacy of original sin that the woman must strive to overcome through her faith.

Despite its undeniable quality and its clear relationship to Rembrandt's portrait style of the mid-1650s, scholars were hesitant to fully attribute this portrait to Rembrandt himself. It was considered the product of an unnamed student or follower, perhaps an artist working in Rembrandt’s studio. However the details revealed during a 2007–2008 conservation treatment made it clear that Woman Holding a Pink was indeed painted by Rembrandt.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 103 x 86 cm (40 9/16 x 33 7/8 in.)

framed: 132.1 x 116.2 cm (52 x 45 3/4 in.) -

Accession Number

1937.1.75

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Pierre Crozat [1665-1740], Paris, before 1740; by inheritance to his nephews, first to Louis-François Crozat, marquis du Châtel [1691-1750], Paris, and then [on Louis-François' death without a male heir] to Louis-Antoine Crozat, baron de Thiers [1699-1770], Paris; the latter's heirs; purchased 1772, through Denis Diderot [1713-1784] as an intermediary, by Catherine II, empress of Russia [1729-1796], for the Imperial Hermitage Gallery, Saint Petersburg; sold March 1931, as a painting by Rembrandt, through (Matthiesen Gallery, Berlin; P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., London; and M. Knoedler & Co., New York) to Andrew W. Mellon, Pittsburgh and Washington, D.C.; deeded 30 March 1932 to The A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, Pittsburgh; gift 1937 to NGA.

Associated Names

- Crozat the Younger, Pierre

- Crozat, marquis du Châtel, Louis-François

- Crozat, baron de Thiers, Louis-Antoine

- Diderot, Denis

- Catherine II of Russia

- The State Hermitage Museum

- M. Knoedler & Company

- P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., Ltd.

- The Matthiesen Gallery

- Mellon, Andrew W.

- The A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust

Exhibition History

1969

Rembrandt in the National Gallery of Art [Commemorating the Tercentenary of the Artist's Death], National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1969, no. 16, repro.

Bibliography

1755

La Curne de Sainte-Palaye, Jean-Baptiste. Catalogue des tableaux du cabinet de M. Crozat, baron de Thiers. Paris, 1755: 32.

1773

Imperial Hermitage Museum [probably Ernst von Münnich, ed.] "Catalogue raisonné des tableaux qui se trouvent dans les Galeries, Sallons et Cabinets du Palais Impérial de S. Pétersbourg, commencé en 1773 et continué jusqu’en 1785.” 3 vols. Manuscript, Fund 1, Opis’ VI-A, delo 85, Hermitage Archives, Saint Petersburg,1773-1783 (vols. 1-2), 1785 (vol. 3): probably no. 1722, as Portrait d'une jeune femme.

1774

Imperial Hermitage Museum [probably Ernst von Münnich, ed.]. Catalogue des tableaux qui se trouvent dans les Cabinets du Palais Impérial à Saint-Pétersbourg. Based on the 1773 manuscript catalogue. Saint Petersburg, 1774: probably no. 1722, as Portrait d'une jeune femme.

1829

Smith, John. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters. 9 vols. London, 1829-1842: 7(1836):171, no. 537.

1838

Imperial Hermitage Museum. Livret de la Galérie Impériale de l'Ermitage de Saint Petersbourg. Saint Petersburg, 1838: 122, no. 10.

1863

Köhne, Baron Bernhard de. Ermitage Impérial, Catalogue de la Galérie des Tableaux. Saint Petersburg, 1863: 173-174, no. 819.

1864

Waagen, Gustav Friedrich. Die Gemäldesammlung in der kaiserlichen Ermitage zu St. Petersburg nebst Bemerkungen über andere dortige Kunstsammlungen. Munich, 1864: 183, no. 819.

1868

Vosmaer, Carel. Rembrandt Harmens van Rijn, sa vie et ses œuvres. The Hague, 1868: 489.

1870

Köhne, Baron Bernhard de. Ermitage Impérial: Catalogue de la Galérie des Tableaux. 3 vols. 2nd ed. Saint Petersburg, 1870: 2:139, no. 819.

1872

Massaloff, Nicolas. Les Rembrandt de l’Ermitage Impérial de Saint-Pétersbourg. Leipzig, 1872: 75, engraved repro. 29.

1879

Ris, Comte Louis Clement de. "Musée Impérial de l’Ermitage à Saint-Pétersbourg (last of 4 articles)." Gazette des Beaux-Arts 20 (November 1879): 382.

1883

Bode, Wilhelm von. Studien zur Geschichte der holländischen Malerei. Braunschweig, 1883: 602, no. 341.

1885

Dutuit, Eugène. Tableaux et dessins de Rembrandt: catalogue historique et descriptif; supplément à l'Oeuvre complet de Rembrandt. Paris, 1885: 39, 63, 69, no. 328.

1886

Wurzbach, Alfred von. Rembrandtgalerie. Stuttgart, 1886: 88, no. 414.

1893

Michel, Émile. Rembrandt: Sa vie, son oeuvre et son temps. Paris, 1893: 416, 567.

1894

Michel, Émile. Rembrandt: His Life, His Work, and His Time. 2 vols. Translated by Florence Simmonds. New York, 1894: 2:97-98, 246.

1895

Somov, Andrei Ivanovich. Ermitage Impérial: Catalogue de la Galérie des Tableaux. 2 vols. 3rd ed. Saint Petersburg, 1895: 2:289, no. 819.

1897

Bode, Wilhelm von, and Cornelis Hofstede de Groot. The Complete Work of Rembrandt. 8 vols. Translated by Florence Simmonds. Paris, 1897-1906: 6:22, 138, no. 453, repro.

1899

Bell, Malcolm. Rembrandt van Rijn and His Work. London, 1899: 181, 189, no. 819.

1901

Somov, Andrei Ivanovich. Ermitage Impérial: Catalogue de la Galérie des Tableaux. 2 vols. 4th ed. Saint Petersburg, 1901: 2:325, no. 819.

1902

Neumann, Carl. Rembrandt. Berlin, 1902: 430-431, repro. 104.

1904

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt: des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. Stuttgart, 1904: 206, repro.

1906

Wurzbach, Alfred von. Niederlandisches Kunstler-Lexikon. 3 vols. Vienna, 1906-1911: 2(1910):409.

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt, des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, 1906: repro. 310, 402.

1907

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. 8 vols. Translated by Edward G. Hawke. London, 1907-1927: 6(1916):402, no. 878.

Bell, Malcolm. Rembrandt van Rijn. The great masters in painting and sculpture. London, 1907: 152.

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt, reproduced in over five hundred illustrations. Classics in Art 2. New York, 1907: 310, repro.

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. Beschreibendes und kritisches Verzeichnis der Werke der hervorragendsten holländischen Maler des XVII. Jahrhunderts. 10 vols. Esslingen and Paris, 1907-1928: 6(1915):363-364, no. 878.

1908

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt, des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. 3rd ed. Stuttgart and Berlin, 1908: repro. 439, 563.

1909

Wrangell, Baron Nicolas. Les Chefs-d’Oeuvre de la Galérie de Tableaux de l’Ermitage Impérial à St. Pétersbourg. London, 1909: xxx, repro. 129.

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt: Des Meisters Gemälde. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. Stuttgart and Leipzig, 1909: repro. 439, 563.

1913

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt, reproduced in over five hundred illustrations. Classics in Art 2. 2nd ed. New York, 1913: repro. 439.

1918

Wrangell, Baron Nicolas. Die Meisterwerke der Gemälde-Galerie in der Ermitage zu St. Petersburg. Edited by Georg Korczewski. 2nd ed. Munich, 1918: xxx, repro 129.

1919

Bode, Wilhelm von. Die Meister der holländischen und vlämischen Malerschulen. 2nd ed. Leipzig, 1919: 30, repro.

1920

Errera, Isabelle. Répertoire des peintures datées. 2 vols. Brussels and Paris, 1920-1921: 1(1920):286.

1921

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Rembrandt: wiedergefundene Gemälde (1910-1922). Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 27. Stuttgart and Berlin, 1921: 439, repro.

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Classics in Art 2. 3rd ed. New York, 1921: 439, repro.

1922

Neumann, Carl. Rembrandt. 2 vols. Revised ed. Munich, 1922: 2:125.

1923

Weiner, Pierre Paul von. Les chefs-d'oeuvre de la Galerie de tableaux de L'Ermitage à Petrograd. Les Chefs-d'Oeuvres des Galeries Principaux de L'Europe 8. Revised ed. Munich, 1923: repro.

Meldrum, David S. Rembrandt’s Painting, with an Essay on His Life and Work. New York, 1923: 138-139, 200, pl. 359.

Weiner, Peter Paul von. Meisterwerke der Gemäldesammlung in der Eremitage zu Petrograd. Revised ed. Munich, 1923: 148, repro.

1935

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt Schilderijen, 630 Afbeeldingen. Utrecht, 1935: no. 390, repro.

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt Gemälde, 630 Abbildungen. Vienna, 1935: no. 390, repro.

1936

Bredius, Abraham. The Paintings of Rembrandt. New York, 1936: no. 390, repro.

1937

Cortissoz, Royal. An Introduction to the Mellon Collection. Boston, 1937: 39.

1941

National Gallery of Art. Preliminary Catalogue of Paintings and Sculpture. Washington, 1941: 165, no. 75.

1942

Book of Illustrations. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1942: 240, repro. 30.

Bredius, Abraham. The Paintings of Rembrandt. 2 vols. Translated by John Byam Shaw. Oxford, 1942: 1:22, no. 390; 2:repro.

1943

Benesch, Otto. "The Rembrandt Paintings in the National Gallery of Art." The Art Quarterly 6, no. 1 (Winter 1943): 27-28, 33 fig. 12.

1949

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Mellon Collection. Washington, 1949 (reprinted 1953 and 1958): 86, repro.

1960

Roger-Marx, Claude. Rembrandt. Translated by W.J. Strachan and Peter Simmons. New York, 1960: 64, 305, no. 131, repro.

1962

Boeck, Wilhelm. Rembrandt. Stuttgart, 1962: 87.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963 (reprinted 1964 in French, German, and Spanish): 313, repro.

1965

National Gallery of Art. Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. Washington, 1965: 109.

1966

Clark, Kenneth. Rembrandt and the Italian Renaissance. New York, 1966: 127, 130, fig. 120.

Bauch, Kurt. Rembrandt Gemälde. Berlin, 1966: 26, no. 515, repro.

1968

Stuffmann, Margret. "Les tableaux de la collection de Pierre Crozat." Gazette des Beaux-Arts 72 (July-September 1968): 11-143, no. 372, repro.

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 96, repro.

1969

National Gallery of Art. Rembrandt in the National Gallery of Art: Commemorating the tercentenary of the artist's death. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1969: 7, 26, no. 16, repro.

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt: The Complete Edition of the Paintings. Revised by Horst Gerson. 3rd ed. London, 1969: repro. 304, 581, no. 390.

1972

La Curne de Sainte-Palaye, Jean-Baptiste de. Catalogue des Tableaux du Cabinet de Crozat, Baron de Thiers. Reprint of the 1755 ed. Geneva, 1972: 32.

1974

Slive, Seymour. "Dutch School." In European Paintings in the Collection of the Worcester Art Museum. Edited by Louisa Dresser. 2 vols. Worcester, 1974: 1:113.

Slive, Seymour. "Dutch School." In European Paintings in the Collection of the Worcester Art Museum. Edited by Louisa Dresser. 2 vols. Worcester, 1974: 1:113.

1975

National Gallery of Art. European paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. Washington, 1975: 284, repro.

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1975: 279, no. 367, color repro.

1976

Watering, Willem L. van de. "On Jacob van Loo’s Portrait of a Young Woman." The Minneapolis Institute of Arts Bulletin 63 (1976–1977): 38, fig. 3.

1977

Bolten, J., and H. Bolten-Rempt. The Hidden Rembrandt. Translated by Danielle Adkinson. Milan and Chicago, 1977: 197, no. 452, repro.

1980

Williams, Robert C.. Russian Art and American Money, 1900-1940. Cambridge, MA, 1980: 173.

1984

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 279, no. 361, color repro., as by Rembrandt van Ryn.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 329, repro.

1991

Kopper, Philip. America's National Gallery of Art: A Gift to the Nation. New York, 1991: 91, 93, color repro.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 321-326, color repro. 323.

2000

Il'in, Nikolas, and Natalia Semënova. Prodannye sokrovishcha Rossii [Sold Treasures of Russia]. Moscow, 2000: 132-133, repro.

2006

Rønberg, Lene Bøgh, and Eva de la Fuente Pedersen. Rembrandt?: The Master and His Workshop. Exh. cat. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, 2006: 250, repro.

2009

Odom, Anne, and Wendy R. Salmond, eds. Treasures into Tractors: The Selling of Russia's Cultural Heritage, 1918-1938. Washington, D.C., 2009: 135 n. 62.

2011

Fiedler, Susanne, and Torsten Knuth. "Vexierbilder einer Biographie: Dr. Heinz Mansfeld (1899-1959)." Mecklenburgische Jahrbücher 126 (2011):308.

2013

Semyonova, Natalya, and Nicolas V. Iljine, eds. Selling Russia's Treasures: The Soviet Trade in Nationalized Art 1917-1938. New York and London, 2013: 138, 158, repro.

2016

Wecker, Menachem. "Famed Arts Patron Catherine the Great had Many Lovers, But She was a Prude." Washington Post 139, no. 120 (April 3, 2016): E2, repro.

Jaques, Susan. The Empress of Art: Catherine the Great and the Transformation of Russia. New York, 2016: 397.

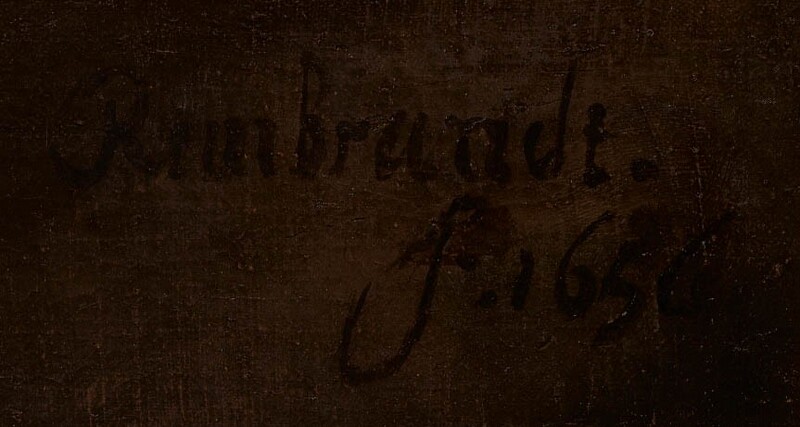

Inscriptions

upper right: Rembrandt. / f.1656

Wikidata ID

Q20177434