Joseph Accused by Potiphar's Wife

1655

Rembrandt Workshop

Painter

Related Artist, Dutch, 1606 - 1669

After learning the fundamentals of drawing and painting in his native Leiden, Rembrandt van Rijn went to Amsterdam in 1624 to study for six months with Pieter Lastman (1583–1633), a famous history painter. Upon completion of his training Rembrandt returned to Leiden. Around 1632 he moved to Amsterdam, quickly establishing himself as the town’s leading artist, specializing in history paintings and portraiture. He received many commissions and attracted a number of students who came to learn his method of painting.

In the seventeenth century, history painting—the depiction of biblical, mythological, and allegorical scenes—was considered the pinnacle of artistic expression. Because such paintings required great imagination and dealt with fundamental moral and ethical issues, theorists ranked history painting before other subjects such as landscape, portraiture, and still life.

The story of Joseph fascinated Rembrandt, who made numerous drawings, prints, and paintings of this Old Testament figure. This particular work, however, was executed by one of Rembrandt’s workshop assistants after the master himself had determined the subject matter and composition. In this scene from the book of Genesis, chapter 39, Potiphar's wife, having failed to seduce Joseph, falsely accuses him of trying to violate her. Speaking to Potiphar, the wife points to the red robe Joseph left behind when he ran from her clutches, wickedly using the presence of the garment as evidence to support her accusation. In the biblical account, Joseph was not present, but the artist added poignancy to his visualization of the story by inserting Joseph on the far side of the bed. Rembrandt’s preoccupation with the theme of false accusation probably stemmed from the drawn-out lawsuit against him by Geertje Dirckx, a former companion, who claimed that he had promised to marry her.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 51

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas transferred to canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 105.7 x 97.8 cm (41 5/8 x 38 1/2 in.)

framed: 130.8 x 123.2 cm (51 1/2 x 48 1/2 in.) -

Accession Number

1937.1.79

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Gerard Hoet, Jr. [d.1760], The Hague; (his sale, by Arnoldus Franken, The Hague, 25-26 August 1760, no. 44).[1] Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky [1710-1775], Berlin; acquired in 1763 by Catherine II, empress of Russia [1729-1796], Saint Petersburg; Imperial Hermitage Gallery, Saint Petersburg; sold January 1931, as a painting by Rembrandt, through (Matthiesen Gallery, Berlin, P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., London, and M. Knoedler & Co., New York) to Andrew W. Mellon, Pittsburgh and Washington; deeded 1 May 1937 to The A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, Pittsburgh;[2] gift 1937 to NGA.

[1] Gerard Hoet, Catalogus of Naamlyst van Schilderijen..., 2 vols., The Hague, 1752, supplement by Pieter Terwesten, 1770, reprint ed. Soest, 1976, 3: 225, no. 44. The painting, which was described as a "kapitaal en uitmuntend stuk," sold for 100 florins.

[2] The Mellon purchase date and the date deeded to the Mellon Trust are according to Mellon collection records in NGA curatorial files and David Finley's notebook (donated to the National Gallery of Art in 1977, now in the Gallery Archives).

In 2012 The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, acquired the M. Knoedler & Co. records (accession number 2012.M.54), and in 2013 processed portions of the archive were first made publicly available. An entry from a January 1931 Knoedler sales book confirms the sale to Mellon (on-line illustration of the sales book page, in Karen Meyer-Roux, "Treasures from the Vault: Knoedler, Mellon, and an Unlikely Sale," The Getty Iris [http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/author/kmeyerroux/], 30 July 2013).

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1933

Loan Exhibition of Paintings by Rembrandt, Knoedler Galleries, New York, 1933, no. 10.

1934

A Century of Progress: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1934, no. 105, repro.

1935

Rembrandt Tentoonstelling, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1935, no. 17.

1969

Rembrandt in the National Gallery of Art [Commemorating the Tercentenary of the Artist's Death], National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1969, no. 13, repro.

1980

Gods, Saints & Heroes: Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; The Detroit Institute of Arts; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1980-1981, no. 28, repro.

1984

In Quest of Excellence: Civic Pride, Patronage, Connoisseurship, Center for the Fine Arts, Miami, 1984, no. 52, repro.

1993

Painting the Bible in Rembrandt's Holland, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1993, no. 161, repro. (catalogue titled Rembrandt's Holland).

1994

Im Lichte Rembrandts: Das Alte Testament im Goldenen Zeitalter der niederländischen Kunst [Rembrandt and the Old Testament], Westfälisches Landesmuseum, Münster, 1994, no. 25, repro.

2003

Rembrandt and the Rembrandt School: The Bible, Mythology and Ancient History, The National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo, 2003, no. 14, repro.

2006

Rembrandt : Quest of a Genius [Rembrandt - Zoektocht van een Genie] [Rembrandt - Genie auf der Suche], Museum Het Rembrandthuis, Amsterdam; Kulturforum, Berlin, 2006, no. 63, repro.

Bibliography

1752

Hoet, Gerard. Catalogus of Naamlyst van Schilderyen. Supplement by Pieter Terwesten. 2 vols. The Hague, 1752-1770: 2(1770):225, no. 44.

1773

Imperial Hermitage Museum [probably Ernst von Münnich, ed.] "Catalogue raisonné des tableaux qui se trouvent dans les Galeries, Sallons et Cabinets du Palais Impérial de S. Pétersbourg, commencé en 1773 et continué jusqu’en 1785.” 3 vols. Manuscript, Fund 1, Opis’ VI-A, delo 85, Hermitage Archives, Saint Petersburg,1773-1783 (vols. 1-2), 1785 (vol. 3): no. 7.

1774

Imperial Hermitage Museum [probably Ernst von Münnich, ed.]. Catalogue des tableaux qui se trouvent dans les Cabinets du Palais Impérial à Saint-Pétersbourg. Based on the 1773 manuscript catalogue. Saint Petersburg, 1774: no. 7, as by Rembrandt.

1828

Schnitzler, Johann Heinrich. Notice sur les principaux tableaux du Musée Impérial de l'Ermitage à Saint-Petersbourg. Saint Petersburg and Berlin, 1828: 57.

1829

Smith, John. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters. 9 vols. London, 1829-1842: 7(1836):8-9, no. 21.

1838

Imperial Hermitage Museum. Livret de la Galérie Impériale de l'Ermitage de Saint Petersbourg. Saint Petersburg, 1838: 128, no. 37.

1859

Blanc, Charles. L’Oeuvre Complet de Rembrandt. 2 vols. Paris, 1859–1861: 2: 259.

1863

Köhne, Baron Bernhard de. Ermitage Impérial, Catalogue de la Galérie des Tableaux. Saint Petersburg, 1863: 169, no. 794.

1864

Waagen, Gustav Friedrich. Die Gemäldesammlung in der kaiserlichen Ermitage zu St. Petersburg nebst Bemerkungen über andere dortige Kunstsammlungen. Munich, 1864: 179, no. 794.

1868

Vosmaer, Carel. Rembrandt Harmens van Rijn, sa vie et ses œuvres. The Hague, 1868: 276, 490.

1870

Köhne, Baron Bernhard de. Ermitage Impérial: Catalogue de la Galérie des Tableaux. 3 vols. 2nd ed. Saint Petersburg, 1870: 2:131, no. 794.

1872

Massaloff, Nicolas. Les Rembrandt de l’Ermitage Impérial de Saint-Pétersbourg. Leipzig, 1872: 4, engraved repro.

1873

Blanc, Charles. L’Oeuvre de Rembrandt. 2 vols. Paris, 1873: 2(1861):259.

1877

Vosmaer, Carel. Rembrandt Harmens van Rijn: sa vie et ses oeuvres. 2nd ed. The Hague, 1877: 551.

1879

Mollett, John W. Rembrandt. Illustrated biographies of the great artists. London, 1879: 93.

Ris, Comte Louis Clement de. "Musée Impérial de l’Ermitage à Saint-Pétersbourg (last of 4 articles)." Gazette des Beaux-Arts 20 (November 1879): 382.

1883

Bode, Wilhelm von. Studien zur Geschichte der holländischen Malerei. Braunschweig, 1883: 508, 599, no. 319.

1885

Dutuit, Eugène. Tableaux et dessins de Rembrandt: catalogue historique et descriptif; supplément à l'Oeuvre complet de Rembrandt. Paris, 1885: 39, 59, 69, no. 14.

1886

Wurzbach, Alfred von. Rembrandtgalerie. Stuttgart, 1886: no. 389.

1893

Michel, Émile. Rembrandt: Sa vie, son oeuvre et son temps. Paris, 1893: 566.

1894

Michel, Émile. Rembrandt: His Life, His Work, and His Time. 2 vols. Translated by Florence Simmonds. New York, 1894: 2:80-81, 245.

1895

Somov, Andrei Ivanovich. Ermitage Impérial: Catalogue de la Galérie des Tableaux. 2 vols. 3rd ed. Saint Petersburg, 1895: 2:273-274, no. 794.

1897

Bode, Wilhelm von, and Cornelis Hofstede de Groot. The Complete Work of Rembrandt. 8 vols. Translated by Florence Simmonds. Paris, 1897-1906: 6:3-4, 34, no. 401, repro.

1899

Bell, Malcolm. Rembrandt van Rijn and His Work. London, 1899: 81, 181.

1901

Somov, Andrei Ivanovich. Ermitage Impérial: Catalogue de la Galérie des Tableaux. 2 vols. 4th ed. Saint Petersburg, 1901: 2:308, no. 794.

1902

Neumann, Carl. Rembrandt. Berlin, 1902: 357-358.

1904

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt: des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. Stuttgart, 1904: 196, repro.

1906

Michel, Émile. Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn: A Memorial of His Tercentenary. New York, 1906: 93.

Veth, Jan. Rembrandt's Leven en Kunst. Amsterdam, 1906: 145.

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt, des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, 1906: xxix-xxx, repro. 301, 403.

Wustmann, Rudolf. "Die Josephgeschichte bei Vondel und Rembrandt." Kunstchronik 18 (23 November 1906): 82–83.

Wurzbach, Alfred von. Niederlandisches Kunstler-Lexikon. 3 vols. Vienna, 1906-1911: 2(1910):409.

1907

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. 8 vols. Translated by Edward G. Hawke. London, 1907-1927: 6(1916):32-33, no. 18.

Bell, Malcolm. Rembrandt van Rijn. The great masters in painting and sculpture. London, 1907: 77, 151.

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt, reproduced in over five hundred illustrations. Classics in Art 2. New York, 1907: 304, repro.

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. Beschreibendes und kritisches Verzeichnis der Werke der hervorragendsten holländischen Maler des XVII. Jahrhunderts. 10 vols. Esslingen and Paris, 1907-1928: 6(1915):16, 17, no. 18.

1908

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt, des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. 3rd ed. Stuttgart and Berlin, 1908: xxxi-xxxii, repro. 376, 561.

1909

Wrangell, Baron Nicolas. Les Chefs-d’Oeuvre de la Galérie de Tableaux de l’Ermitage Impérial à St. Pétersbourg. London, 1909: xxix, repro. 121.

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt: Des Meisters Gemälde. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. Stuttgart and Leipzig, 1909: xxxi-xxxii, repro. 376, 561.

1911

Bénézit, Emmanuel. Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs & graveurs de tous les temps et de tous les pays. 3 vols. Paris, 1911: 3:617, 619 .

1913

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt, reproduced in over five hundred illustrations. Classics in Art 2. 2nd ed. New York, 1913: 20, repro. 376.

1918

Wrangell, Baron Nicolas. Die Meisterwerke der Gemälde-Galerie in der Ermitage zu St. Petersburg. Edited by Georg Korczewski. 2nd ed. Munich, 1918: xxix, repro. 121.

1920

Errera, Isabelle. Répertoire des peintures datées. 2 vols. Brussels and Paris, 1920-1921: 1(1920):282, dated 1655.

1921

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Classics in Art 2. 3rd ed. New York, 1921: 20, 376, repro.

1922

Neumann, Carl. Rembrandt. 2 vols. Revised ed. Munich, 1922: 2:383-384.

1923

Weiner, Peter Paul von. Meisterwerke der Gemäldesammlung in der Eremitage zu Petrograd. Revised ed. Munich, 1923: 138, repro.

Meldrum, David S. Rembrandt’s Painting, with an Essay on His Life and Work. New York, 1923: 201, pl. 396.

Van Dyke, John C. Rembrandt and His School. New York, 1923: 39.

Weiner, Pierre Paul von. Les chefs-d'oeuvre de la Galerie de tableaux de L'Ermitage à Petrograd. Les Chefs-d'Oeuvres des Galeries Principaux de L'Europe 8. Revised ed. Munich, 1923: repro.

1924

Bénézit, Emmanuel. Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs & graveurs de tous les temps et de tous les pays. 3 vols. Paris, 1911-1924: 3:617, 619.

1933

"American Art Notes [Rembrandt Loan Exhibition]." _The Connoisseur _ 91 (April 1933): 275-277, repro.

Watson, Forbes. "Gallery Explorations." Parnassus 5 (April 1933): 1-2, repro.

Rich, Daniel Catton, ed. A Century of Progress: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture. Exh. cat. Art Institute of Chicago, 1933: 18-19, no. 105.

M. Knoedler & Co. Loan exhibition of paintings by Rembrandt. Exh. cat. M. Knoedler & Co., New York, 1933: no. 10.

Frankfurter, Alfred M. "New York's First Rembrandt Exhibition." The Fine Arts (May 1933): 8, repro. on cover.

1935

Chamot, Mary. "The Rembrandt and Vermeer Exhibitions." Apollo 22 (October 1935): 201, repro.

Rich, Daniel Catton. "Rembrandt Remains." Parnassus 7 (October 1935): 3-5, repro.

Scharf, Alfred. "Dutch and Flemish Painting at the Brussels, Amsterdam and Rotterdam Exhibitions." Connoisseur 96 (November 1935): 250.

Schmidt-Degener, Frederik. Rembrandt Tentoonstelling, ter herdenking van de plechtige opening van het Rijksmuseum. Exh. cat. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1935: no. 17.

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt Schilderijen, 630 Afbeeldingen. Utrecht, 1935: no. 523, repro.

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt Gemälde, 630 Abbildungen. Vienna, 1935: no. 523, repro.

1936

Bredius, Abraham. The Paintings of Rembrandt. New York, 1936: no. 523, repro.

“Die sowjetrussischen Kunstverkäufe.” Die Weltkunst 47 (29 November 1936): 1, repro.

1941

National Gallery of Art. Preliminary Catalogue of Paintings and Sculpture. Washington, 1941: 166, no. 79.

1942

National Gallery of Art. Book of illustrations. 2nd ed. Washington, 1942: 79, repro. 31, 240.

Bredius, Abraham. The Paintings of Rembrandt. 2 vols. Translated by John Byam Shaw. Oxford, 1942: 1:31, no. 523; 2:repro.

1943

Benesch, Otto. "The Rembrandt Paintings in the National Gallery of Art." The Art Quarterly 6, no. 1 (Winter 1943): 27, 29 fig. 8.

1948

Rosenberg, Jakob. Rembrandt. 2 vols. Cambridge, MA, 1948: 1:137.

1949

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Mellon Collection. Washington, 1949 (reprinted 1953 and 1958): 85, repro.

1954

Münz, Ludwig. Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn. The Library of Great Painters. New York, 1954: 114.

Benesch, Otto. The Drawings of Rembrandt: A Critical and Chronological Catalogue. 6 vols. London, 1954-1957: 5(1957):277.

1960

Goldscheider, Ludwig. Rembrandt Paintings, Drawings and Etchings. London, 1960: 177, no. 85, repro.

Roger-Marx, Claude. Rembrandt. Translated by W.J. Strachan and Peter Simmons. New York, 1960: 72-73, 280.

Bauch, Kurt. Der frühe Rembrandt und seine Zeit: Studien zur geschichtlichten Bedeutung seines Frühstils. Berlin, 1960: 258 n. 96.

1962

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds. Treasures from the National Gallery of Art. New York, 1962: 98, color repro.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963 (reprinted 1964 in French, German, and Spanish): 182, repro.

1964

Rosenberg, Jakob. Rembrandt: Life and Work. Revised ed. Greenwich, Connecticut, 1964: 222.

1965

Krieger, Peter. "Die Berliner Rembrandt-Sammlung." Speculum Artis 17 (February 1965): 14.

National Gallery of Art. Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. Washington, 1965: 109.

1966

Bauch, Kurt. Rembrandt Gemälde. Berlin, 1966: 3, no. 33, repro.

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds. A Pageant of Painting from the National Gallery of Art. 2 vols. New York, 1966: 1: 230, color repro., as by Rembrandt.

1967

Regteren Altena, J.Q. van. "Review of Bauch 1966." Oud Holland 82 (1967): 69-71.

1968

Gerson, Horst. Rembrandt Paintings. Amsterdam, 1968: 114, 116, 362-363, repro., 499.

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 96, repro.

1969

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt: The Complete Edition of the Paintings. Revised by Horst Gerson. 3rd ed. London, 1969: repro. 432, 601, no. 523.

National Gallery of Art. Rembrandt in the National Gallery of Art: Commemorating the tercentenary of the artist's death. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1969: 6, 23, no. 13, repro.

1970

Benesch, Otto. Otto Benesch Collected Writings. 2 vols. Edited by Eva Benesch. London and New York, 1970: 1:83-100, 140-146, fig. 69.

1973

Kauffmann, Hans. "Anmerkungen zu Rembrandts Potipharbildern." In Neue Beiträge zur Rembrandt-Forschung. Edited by Otto von Simson and Jan Kelch. Berlin, 1973: 50-57, fig. 14.

Benesch, Otto. The Drawings of Rembrandt. 6 vols. Edited by Eva Benesch. Enlarged ed. London, 1973: 5:265.

Klessmann, Rudiger. "Zum Röntgen-Befund des Potiphar-Bildes in Berlin." In Neue Beiträge zur Rembrandt-Forschung. Edited by Otto Georg von Simson and Jan Kelch. Berlin, 1973: 44-49, fig. 14.

1974

Potterton, Homan. "'A Commonplace Practitioner in Painting and in Etching': Charles Exshaw." The Connoisseur 187 (December 1974): 273, fig. 8 (etching after the painting).

1975

National Gallery of Art. European paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. Washington, 1975: 286, repro.

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1975: 280, no. 371, color repro.

1976

Hoet, Gerard. Catalogus of naamlyst van schilderyen. 3 vols. Reprint of 1752 ed. with supplement by Pieter Terwesten, 1770. Soest, 1976: 3:225, no. 44.

1977

Bolten, J., and H. Bolten-Rempt. The Hidden Rembrandt. Translated by Danielle Adkinson. Milan and Chicago, 1977: 196, no. 437, repro.

1980

Blankert, Albert, et al. Gods, Saints, and Heroes: Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington; Detroit Institute of Arts; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Washington, 1980: 148-149, no. 28, repro.

Williams, Robert C.. Russian Art and American Money, 1900-1940. Cambridge, MA, 1980: 173.

1984

Tümpel, Christian. "Die Rezeption der Jüdischen Altertümer des Flavius Josephus in den holländischen Historiendarstellungen des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts." In Wort und Bild in der Niederländischen Kunst und Literatur des 16. u. 17. Jahrhunderts. Edited by H. Vekeman and J. Müller Hofstede. Erfstadt, 1984: 191, pl. 28.

Schwartz, Gary. Rembrandt: Zijn leven, zijn schilderijen. Maarssen, 1984: 272, 274-275, no. 310, repro.

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 280, no. 365, color repro., as by Rembrandt van Ryn.

Marck, Jan van der. In quest of excellence: civic pride, patronage, connoisseurship. Exh. cat. Center for the Fine Arts, Miami, 1984: 232, 239, no. 52, repro.

Münz, Ludwig. Rembrandt. Revised ed. London, 1984: 96.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 330, repro.

Schwartz, Gary. Rembrandt: His Life, His Paintings. New York, 1985: 173, 272, 274-275, no. 310, repro.

1986

Sutton, Peter C. A Guide to Dutch Art in America. Washington and Grand Rapids, 1986: 312.

Tümpel, Christian. Rembrandt. Translated by Jacques and Jean Duvernet, Léon Karlson, and Patrick Grilli. Paris, 1986: repro. 279, 419, no. A2.

1991

Bal, Mieke. Reading "Rembrandt": beyond the word-image opposition. Cambridge New Art History and Criticism. Cambridge, 1991: 34-39, 43, 46-48, 105-108, 117, 123, 140, 199, 217, 405 n. 24, 451 n.13, repros. 1.2, 1.7, 3.4.

Tümpel, Christian. Het Oude Testament in de schilderkunst van de Gouden Eeuw. Exh. cat. Joods Historisch Museum, Amsterdam; Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Zwolle, 1991: 200.

Kopper, Philip. America's National Gallery of Art: A Gift to the Nation. New York, 1991: 91, 94, color repro.

1992

National Gallery of Art. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1992: 131, repro.

1993

Baron, Jean-Marie, and Pascal Bonafoux. Rembrandt, la Bible. Paris, 1993: 52-53, repro.

Weyl, Martin, and Rivka Weiss-Blok, eds. Rembrandt shel Holland [Rembrandt's Holland]. Exh. cat. Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1993: 163, no. 161, repro.

1994

Tümpel, Christian. Im Lichte Rembrandts: das Alte Testament im Goldenen Zeitalter der niederländischen Kunst. Exh. cat. Westfälisches Landesmuseum, Münster. Zwolle, 1994: 45, 251-252, no. 25, repro.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 314-321, color repro. 315.

1997

Blankert, Albert. Rembrandt: A Genius and his Impact, Exh. cat. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Zwolle, 1997: 141, no. 16e, repro.

1998

Lindgren, Claire. "Calumny." In Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography: Themes Depicted in Works of Art. Edited by Helene E. Roberts. 2 vols. Chicago, 1998: 1:153.

Roberts, Helene E., ed. Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography: Themes Depicted in Works of Art. 2 vols. Chicago, 1998: 1:130, 153.

2000

Il'in, Nikolas, and Natalia Semënova. Prodannye sokrovishcha Rossii [Sold Treasures of Russia]. Moscow, 2000: 118, 119, repro.

2001

Lloyd Williams, Julia. Rembrandt's Women. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh; Royal Academy of Arts, London. London, 2001: 210, fig. 146.

2003

Kofuku, Akira. Rembrandt and the Rembrandt School: The Bible, Mythology and Ancient History. Exh. cat. Kokuritsu Seiyo Bijutsukan, Tokyo, 2003: 84-85, no. 14, repro.

Korthals Altes, Everhard. De verovering van de internationale kunstmarkt door de zeventiende-eeuwse schilderkunst: enkele studies over de verspreiding van Hollandse schilderijen in de eerste helft van de achttiende eeuw. Leiden, 2003: 152-153, repro.

2006

Rønberg, Lene Bøgh, and Eva de la Fuente Pedersen. Rembrandt?: The Master and His Workshop. Exh. cat. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, 2006: 118-120, fig. 22.

Wetering, Ernst van de. "Rembrandt's Art: Attempting an Objective Evaluation." In Rembrandt: Quest of a Genius. Edited by Ernst van de Wetering. Exh. cat. Museum Het Rembrandthuis, Amsterdam; Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. Zwolle, 2006: 239-244, fig. 267.

2009

Odom, Anne, and Wendy R. Salmond, eds. Treasures into Tractors: The Selling of Russia's Cultural Heritage, 1918-1938. Washington, D.C., 2009: 135 n. 62.

2011

Fiedler, Susanne, and Torsten Knuth. "Vexierbilder einer Biographie: Dr. Heinz Mansfeld (1899-1959)." Mecklenburgische Jahrbücher 126 (2011):307-308.

2013

Semyonova, Natalya, and Nicolas V. Iljine, eds. Selling Russia's Treasures: The Soviet Trade in Nationalized Art 1917-1938. New York and London, 2013: 138, 144, repro.

2014

Bikker, Jonathan, and Gregor J.M. Weber. Rembrandt: The Late Works. Exh. cat. National Gallery, London; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. London, 2014: 241, 243 fig. 81.

2016

Wecker, Menachem. "Famed Arts Patron Catherine the Great had Many Lovers, But She was a Prude." Washington Post 139, no. 120 (April 3, 2016): E2, repro.

Jaques, Susan. The Empress of Art: Catherine the Great and the Transformation of Russia. New York, 2016: 397, 398.

Inscriptions

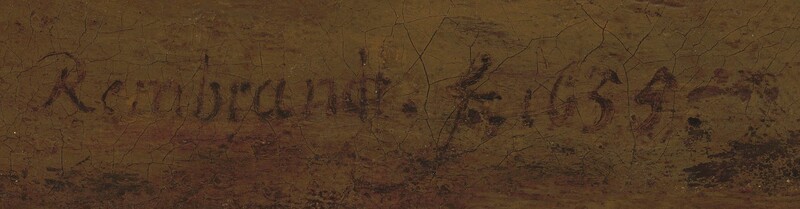

lower right: Rembrandt. f.1655.

Wikidata ID

Q21485158