Jean Honoré Fragonard

Fragonard, Jean-Honoré

French, 1732 - 1806

Fragonard was one of the most prolific of the eighteenth-century painters and draftsmen. Born in 1732 in Grasse in southern France, he moved with his family at an early age to Paris. He first took a position as a clerk, but having demonstrated an interest in art, he worked in the studio of the still life and genre painter Jean Siméon Chardin (1699-1779). After spending a short time with Chardin, from whom he probably learned merely the bare rudiments of his craft, he entered the studio of François Boucher (1703-1770). Under Boucher’s tutelage Fragonard’s talent developed rapidly, and he was soon painting decorative pictures and pastoral subjects very close to his master’s style (for example, Diana and Endymion). Although Fragonard apparently never took courses at the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, he entered the Prix de Rome competition in 1752, sponsored by Boucher, winning the coveted first prize on the strength of Jeroboam Sacrificing to the Idols (Paris, École des Beaux-Arts). Before leaving for Italy, however, he entered the École des élèves protégés in Paris, a school established to train the most promising students of the Académie royale. There he studied history and the classics and worked with the director, Carle Van Loo (1705-1765), one of the leading painters of the day. Van Loo’s influence on Fragonard’s art is evident in the large Psyche Showing Her Sisters the Gifts She Has Received from Cupid (London, National Gallery), a fluidly painted work that was exhibited to King Louis XV (r. 1715–1774) in 1754.

Following his stint at the École, Fragonard traveled to Italy, spending the years 1756–1761 at the Académie de France in Rome. Fragonard’s slow progress (or his unwillingness to complete his assigned artistic chores) concerned the director, Charles Joseph Natoire (1700-1777), but the young artist showed greater promise when he was steered toward sketching in the open air, a practice that Natoire encouraged. Inspired by such landscapists active in Italy as Hubert Robert (1733-1808) and Claude Joseph Vernet (1714-1789) and by the patronage of the Abbé de Saint-Non (1727–1791), an accomplished amateur and avid collector, Fragonard developed an interest in landscape painting and drawing that would remain an important aspect of his art throughout his life. During the summer of 1760, spent with Saint-Non at the Villa d’Este in Tivoli, Fragonard produced a series of red chalk drawings of the gardens and principal sites of the town that are among the greatest examples of landscape art of the century. He returned to France in the company of Saint-Non, with whom he had traveled extensively through Italy, making drawings of the principal architectural sites and works of art that they encountered. Saint-Non later used these drawings as the basis for a series of etchings and aquatints.

Back in Paris, Fragonard painted small cabinet pictures—primarily landscapes and genre scenes—for the art market and a growing group of admirers. He made his public debut at the Salon of 1765 with the stunning Corésus and Callirhoé (Paris, Musée du Louvre), a monumental canvas that seemed to herald his arrival as the most promising history painter of his generation. The grand machine won him probationary acceptance into the Académie and the accolades of the critic Denis Diderot (1713-1784), who discussed the picture at length in his Salon review in the Correspondance littéraire. Despite this early success, Fragonard declined to pursue a public career as a history painter, preferring to work for a private clientele of financiers and courtiers. The failure of the crown to reimburse him promptly for the Corésus may have been a factor in his decision. As a result, little documentation and critical commentary concerning Fragonard’s art survives, and only recently has the development of his career, his patrons, and the significance of his innovative imagery begun to be fully explored, notably in the exhibition held in Paris and New York in 1987–1988.

Nevertheless, Fragonard is rightly considered among the most characteristic and important French painters of the second half of the eighteenth century. Over four decades, he produced many brilliantly realized easel paintings, such as The Swing (London, Wallace Collection), commissioned in 1767, or the Portraits de fantaisie (Paris, Musée du Louvre, and elsewhere), painted in the late 1760s and early 1770s; and large-scale decorative works, the most significant extant example being the four magisterial canvases known as the Progress of Love (1771–1772; New York, Frick Collection), commissioned by Madame du Barry (1743–1793) for her country retreat at Louveciennes. These paintings marked Fragonard as among the most innovative and brilliant painters of the day, yet his apparently whimsical temperament and independent ways meant that he never realized the conventional rewards his talent deserved. The Louveciennes paintings were returned to the artist, replaced by drier yet more currently neoclassical compositions by Joseph Marie Vien (1716–1809) (Paris, Musée du Louvre, and Paris, Château de Chambéry), and other commissions were left incomplete. Yet Fragonard earned a good living selling paintings to a close-knit group of collectors, many of them drawn from the ranks of the fermiers généraux (tax farmers), and by providing brilliant wash drawings as illustrations for various luxurious book publishing projects.

A second trip to Italy in 1773–1774 in the company of the financier Pierre Jacques Onésyme Bergeret de Grancourt (1715–1785), one of the artist’s major patrons, rekindled Fragonard’s interest in landscape and garden imagery, leading to such masterpieces as the Fête at Saint-Cloud (Paris, Banque de France) and the pendants Blindman’s Buff and The Swing (NGA), datable to the late 1770s. During these years Fragonard also produced numerous ink and wash drawings whose broad handling and vivid luminosity reflect an ever-increasing self-assurance and technical command. Always a changeable artist, he simultaneously painted tightly wrought cabinet pictures in an erotic vein, the most celebrated example being The Bolt (c. 1777–1778; Paris, Musée du Louvre), made popular through engravings. Such late works—highly finished pictures focusing on intimate themes—show a fascination with the goût hollandais, an influence he passed on to his only true student, his sister-in-law Marguerite Gérard (1761-1837), with whom he sometimes collaborated. Certain of Fragonard’s later paintings, like The Invocation to Love, known in numerous versions, also demonstrate a darker, more emotional character that anticipates romanticism. During the revolution Fragonard left Paris for his native Grasse, taking with him The Progress of Love cycle, which he reassembled in the house of his cousin. In 1793 he returned to Paris, where his old acquaintance Jacques Louis David (1748-1845) appointed him a curator at the new national museum. During the last decade of his life his artistic production lessened, perhaps in the recognition that his late rococo style was out of step with the times. He died in 1806.

This text was previously published in Philip Conisbee et al., French Paintings of the Fifteenth through the Eighteenth Century, The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue (Washington, DC, 2009), 149–150.

Explore Selected Works

See all 379 works of artArtwork

The Visit to the Nursery

The Visit to the Nursery

Jean Honoré Fragonard · c. 1775 · oil on canvas · Accession ID 1946.7.7

Artwork

A Game of Horse and Rider

A Game of Horse and Rider

Jean Honoré Fragonard · c. 1775/1780 · oil on canvas · Accession ID 1946.7.5

Artwork

A Game of Hot Cockles

A Game of Hot Cockles

Jean Honoré Fragonard · c. 1775/1780 · oil on canvas · Accession ID 1946.7.6

Artwork

Blindman's Buff

Blindman's Buff

Jean Honoré Fragonard · c. 1775/1780 · oil on canvas · Accession ID 1961.9.16

Artwork

Love the Sentinel

Love the Sentinel

Jean Honoré Fragonard · c. 1773/1776 · oil on canvas · Accession ID 1947.2.2

Artwork

Love as Folly

Love as Folly

Jean Honoré Fragonard · c. 1773/1776 · oil on canvas · Accession ID 1947.2.1

Artwork

Love as Folly

Love as Folly

Jean Honoré Fragonard · c. 1773/1776 · oil on canvas · Accession ID 1970.17.111

Artwork

Love the Sentinel

Love the Sentinel

Jean Honoré Fragonard · c. 1773/1776 · oil on canvas · Accession ID 1970.17.112

Artwork

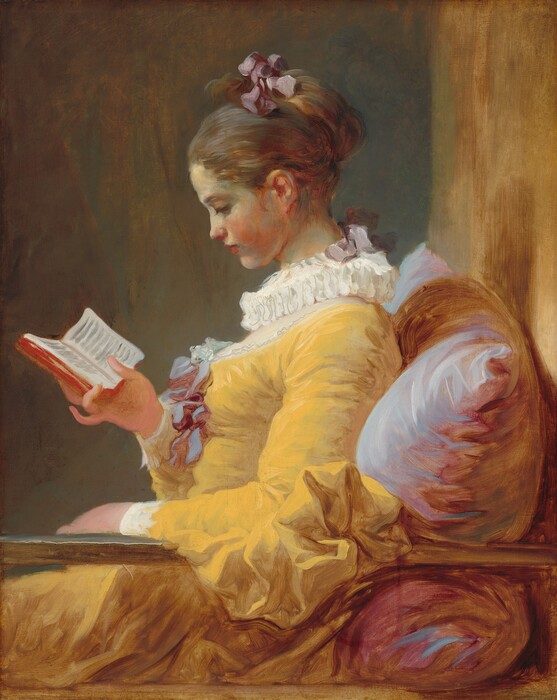

Young Girl Reading

Young Girl Reading

Jean Honoré Fragonard · c. 1769 · oil on canvas · Accession ID 1961.16.1

Bibliography

1880

Goncourt, Edmond de, and Jules de Goncourt. L’art du dix-huitième siécle. 2 vols. Paris, 1880–1884.

1889

Portalis, Roger. Honoré Fragonard: sa vie et son oeuvre. 2 vols. Paris, 1889.

1906

Nolhac, Pierre de. J.-H. Fragonard (1732– 1806). Paris, 1906.

1956

Réau, Louis. Fragonard, sa vie et son oeuvre. Brussels, 1956.

1960

Wildenstein, Georges. The Paintings of Fragonard: Complete Edition. New York, 1960.

1972

Wildenstein, Daniel, and Gabriele Mandel. L’opera completa di Fragonard. Milan, 1972.

1987

Cuzin, Jean-Pierre. Fragonard, Life and Work. New York, 1988. French ed. Paris, 1987.

Rosenberg, Pierre. Fragonard. Exh. Cat. Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris and Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1987.

1989

Rosenberg, Pierre. Tout l’oeuvre peint de Fragonard. Paris, 1989.

2009

Conisbee, Philip, et al. French Paintings of the Fifteenth through the Eighteenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, D.C., 2009: 149-150.