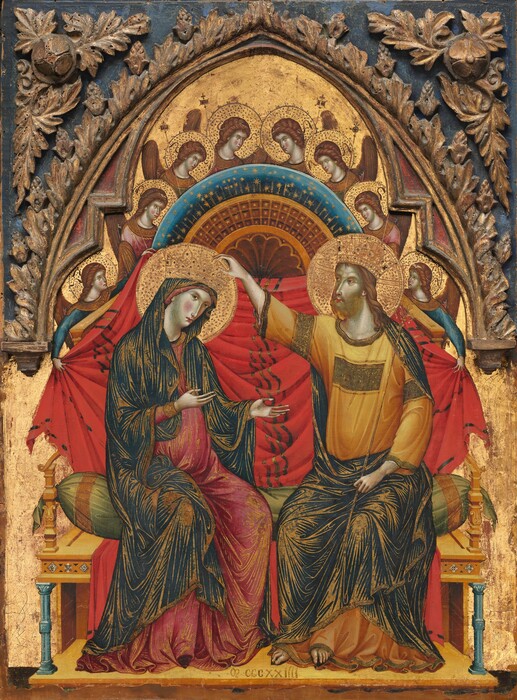

Master of the Washington Coronation

Explore Selected Works

Artwork

Bibliography

1969

Muraro, Michelangelo. Paolo da Venezia. Milan, 1969: 29-32.

1992

Lucco, Mauro. “Maestro dell’Incoronazione della Vergine di Washington” and “Marco di Martino da Venezia (Marco Veneziano).” La Pittura nel Veneto. Il Trecento. Edited by Mauro Lucco. 2 vols. Milan, 1992: 2:534-535, 541-542.

1996

Gibbs, Robert. “Master of the Washington Coronation.” In The Dictionary of Art. Edited by Jane Turner. 34 vols. New York and London, 1996: 20:784-785.

1997

Santini, Clara. “Un episodio della pittura veneziana di primo Trecento: Il ‘Maestro dell’Incoronazione della Vergine di Washington.’” Il Santo 37 (1997): 123-145.

2007

Guarnieri, Cristina. “Il passaggio tra due generazioni: Dal Maestro dell’Incoronazione a Paolo Veneziano.” In Il secolo di Giotto nel Veneto. Edited by Giovanna Valenzano and Federica Toniolo. Venice, 2007: 153-177.

2016

Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. The Systematic Catalogue of the National Gallery of Art. Washington, 2016: 301-302.