Master of Città di Castello

Explore Selected Works

Artwork

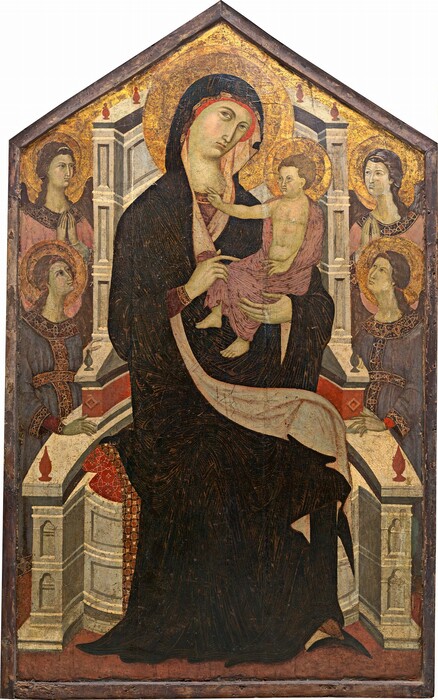

Maestà (Madonna and Child with Four Angels)

Maestà (Madonna and Child with Four Angels)

Master of Città di Castello c. 1290

Bibliography

1908

Perkins, F. Mason. “Alcuni appunti sulla Galleria delle Belle Arti di Siena.”Rassegna d’Arte Senese 4 (1908): 51–52.

1923

Marle, Raimond van. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. 19 vols. The Hague, 1923-1938: 2(1924):80-85.

1968

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance. Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London, 1968: 2:249.

1977

Cole, Bruce. Agnolo Gaddi. Oxford, 1977.

1979

Stubblebine, James H. Duccio di Buoninsegna and His School. 2 vols. Princeton, 1979: 1:85-89.

2001

Freuler, Gaudenz. “Duccio et ses contemporains: le maître de Città di Castello.” Revue de l’Art 134 (2001): 27-50.

2003

Bagnoli, Alessandro. In Duccio: Siena fra tradizione bizantina e mondo gotico. Edited by Alessandro Bagnoli, Roberto Bartalini, Luciano Bellosi, and Michel Laclotte. Milan, 2003: 314-326.

2016

Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. The Systematic Catalogue of the National Gallery of Art. Washington, 2016: 262-263.