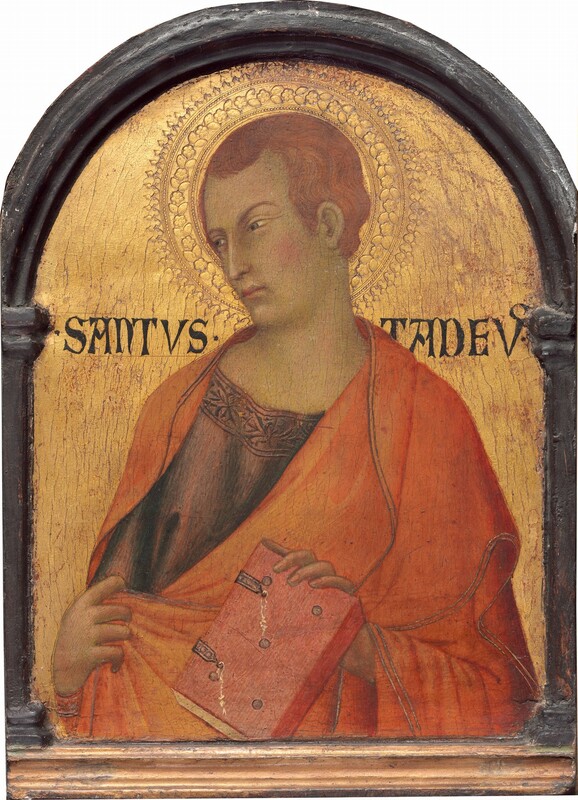

Saint Judas Thaddeus

c. 1315/1320

Simone Martini

Painter, Sienese, active from 1315; died 1344

Saint Judas Thaddeus once decorated the predella of an altarpiece along with nine other small portraits of apostles, three of which are in the collection of the National Gallery of Art: Matthew, Simon, and James Major. This panel of Saint Judas Thaddeus is among the best preserved of the four and the softness of the modeling displays most clearly Simone Martini’s refined pictorial manner. With his head bowed to one side, the apostle turns away from the viewer to contemplate something or someone beyond the frame of representation. The dreamy introspective air of the young saint is complemented by the delicacy of his gestures, particularly the way in which he draws the fingers of his right hand through the fabric of his mantle. The spontaneous naturalism of this action distinguishes Simone's works from those of his peers.

One of the 12 apostles of Jesus, Saint Judas Thaddeus is identified in the Gospels of Mark and Matthew, as "Thaddeus." In Luke, John, and the Acts of the Apostles, he is known simply as "Judas." However, he is not to be confused with Judas Iscariot, the traitor. Saint Judas Thaddeus's most prominent role in the biblical narrative takes place during the Last Supper (the Passover meal Jesus shared with his apostles the night before he was crucified). In the midst of Jesus's explanation of what was to come, including the assertion that he would return to them, Judas Thaddeus asked an important question. John 14:22: "Judas (not Iscariot) said to him, 'Lord, how is it that you will reveal yourself to us, and not to the world?'” Jesus responded by foretelling the descent of the Holy Spirit on his followers, an event that occurred on Pentecost.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 1

Artwork overview

-

Medium

tempera on panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

painted surface: 26 x 19.7 cm (10 1/4 x 7 3/4 in.)

overall: 30.7 x 23.3 cm (12 1/16 x 9 3/16 in.)

framed: 44.4 x 60 cm (17 1/2 x 23 5/8 in.) -

Accession Number

1952.5.26

Associated Artworks

Saint Matthew

Simone Martini

1315

Saint Simon

Simone Martini

1315

Saint James Major

Simone Martini

1315

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Acquired between 1832 and 1842 by Johann Anton Ramboux [1790-1866], Cologne, together with six other components of the same series, presumably in Siena;[1] (his estate sale, J.M. Heberle, Cologne, 23 May 1867, no. 75 [all ten panels], as by Lippo Memmi);[2] the whole series purchased by the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne, which deaccessioned it in 1922-1923;[3] the four NGA panels, 1952.5.23-.26, purchased together with a fifth panel of the same series, by Philip Lehman [1861-1947], New York, by 1928;[4] the four NGA panels sold June 1943 to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, New York;[5] gift 1952 to the NGA.

[1] Ramboux built up his huge collection of early Italian pictures essentially in the above-mentioned years of his second period of residence in Italy; see Christoph Merzenich,"Di dilettanza per un artista - Der Sammler Antonio Giovanni Ramboux in der Toskana," in Lust und Verlust, edited by Hiltrud Kier and Frank Günter Zehnder, 2 vols., Cologne, 1995-1998: 1(1995): 303–314.

[2] Without quoting their provenance, the sale catalogue entry states only that the ten busts “ . . . stimmen im Ausdruck wie in der übrigen Technik mit den Wandmalereien im Stadthause zu Sangeminiano überein.”

[3] See Kier and Zehnder 1995-1998, 2(1998): 550-552.

[4] The four panels in Washington and a fifth, representing Saint Philip, are included in the catalogue of the Lehman collection (Robert Lehman, The Philip Lehman Collection, New York, Paris, 1928: nos. xix-xxiii). Possibly, Philip Lehman acquired them through Edward Hutton in London, who also handled the panels of the series now in The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

[5] The bill of sale for the Kress Foundation’s purchase of fifteen paintings from the Lehman collection, including NGA 1952.5.23-.26, is dated 11 June 1943; payment was made four days later (copy in NGA curatorial files). The documents concerning the 1943 sale all indicate that Philip Lehman’s son Robert Lehman (1892-1963) was owner of the paintings, but it is not clear in the Lehman Collection archives at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, whether Robert made the sale for his father or on his own behalf. See Laurence Kanter’s e-mail of 6 May 2011, about ownership of the Lehman collection, in NGA curatorial files. See also The Kress Collection Digital Archive, https://kress.nga.gov/Detail/objects/1906.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1946

Recent Additions to the Kress Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1946, no. 823.

Bibliography

1862

Katalog der Gemälde Alter italienischer Meister (1221-1640) in der Sammlung des Conservator J. A. Ramboux. Cologne, 1862: 15, no. 75.

1864

Crowe, Joseph Archer, and Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle. A New History of Painting in Italy from the Second to the Sixteenth Century. 3 vols. London, 1864-1866: 2(1864):105.

1867

Heberle, J. M. Catalog der nachgelassenen Kunst-Sammlungen des Herrn Johann Anton Ramboux. Cologne, 23 May 1867: 17, no. 75.

1869

Niessen, Johannes. Verzeichniss der Gemälde-Sammlung des Museums Wallraf-Richartz in Köln. Cologne, 1869: 137.

1897

Berenson, Bernard. The Central Italian Painters of the Renaissance. New York, 1897: 148.

1901

Venturi, Adolfo. _Storia dell’arte italiana. 11 vols. Milan, 1901-1940: 5(1907):666-667 n. 1.

1903

Crowe, Joseph Archer, and Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle. A History of Painting in Italy from the Second to the Sixteenth Century. 6 vols. Edited by Robert Langton Douglas (vols. 1-4) and Tancred Borenius (vols. 5-6). Vol. 3, The Sienese, Umbrian, and North Italian Schools. London, 1903-1914: 3(1908):76, 76-77 n. 5.

1907

Perkins, Frederick Mason. "Simone di Martino (Simone Martini)." In Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Edited by Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker. 37 vols. Leipzig, 1907-1950: 31(1937):67.

1909

Berenson, Bernard. The Central Italian Painters of the Renaissance. 2nd ed. New York, 1909: 202.

1926

Gielly, Louis. Les primitifs siennois. Paris, 1926: 111.

1928

Lehman, Robert. The Philip Lehman Collection, New York: Paintings. Paris, 1928: no. XIX, repro.

1930

Mayer, August L. "Die Sammlung Philip Lehman." Pantheon 5 (1930): 113.

1931

Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. Milan, 1931: no. 61, repro.

1932

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford, 1932: 534.

Marle, Raimond van. Le scuole della pittura italiana. 2 vols. The Hague and Florence, 1932-1934: 2(1934):258 n.

1933

Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. Translated by Countess Vanden Heuvel and Charles Marriott. 3 vols. New York and Milan, 1933: 1:no. 77, repro.

1936

Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del rinascimento: catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opere con un indice dei luoghi. Translated by Emilio Cecchi. Milan, 1936: 459.

1939

McCall, George. Masterpieces of Art. Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture from 1300-1800. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Exh. cat. World’s Fair, New York, 1939: 116-117.

1945

Paintings and Sculpture from the Kress Collection. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1945 (reprinted 1947, 1949): 17, repro., as by Simone Martini and Assistants.

1946

Douglas, Robert Langton. "Recent Additions to the Kress Collection." The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 88 (1946): 85.

1951

Toesca, Pietro. Il Trecento. Storia dell’arte italiana, 2. Turin, 1951: 551 n. 75.

1956

Coor, Gertrude. "Trecento-Gemälde aus der Sammlung Ramboux." Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch 18 (1956): 118.

1957

Exposition de la Collection Lehman de New York. Exh. cat. Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, 1957: 43.

1959

Paintings and Sculpture from the Samuel H. Kress Collection. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1959: 33, repro., as by Simone Martini and Assistants.

1965

Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 123, as by Simone Martini and Assistants.

1966

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools, XIII-XV Century. London, 1966: 48-49, fig. 122.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 110, repro., as by Simone Martini and Assistants.

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance. Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London, 1968: 1:404.

1970

Contini, Gianfranco, and Maria Cristina Gozzoli. L’opera completa di Simone Martini. Milan, 1970: 105 no. 53, repro.

1972

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass., 1972: 122, 451, 646, 665.

1974

De Benedictis, Cristina. "A proposito di un libro su Buffalmacco." Antichità viva 13, no. 2 (1974): 8, 10 n. 13.

Mallory, Michael. "An Altarpiece by Lippo Memmi Reconsidered." Metropolitan Museum Journal 9 (1974): 201 n. 19.

1975

European Paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1975: 328, repro., as by Simone Martini and Assistants.

1977

Torriti, Piero. La Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena. I Dipinti dal XII al XV secolo. Genoa, 1977: 90.

1978

Ressort, Claude, Sylvia Beguin, and Michel Laclotte, eds. Retables italiens du XIIIe au XVe siècle. Exh. cat. Musée National du Louvre, Paris, 1978: 19.

1979

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Catalogue of the Italian Paintings. National Gallery of Art. 2 vols. Washington, 1979: 1:432-433; 2:pl. 310.

De Benedictis, Cristina. La pittura senese 1330-1370. Florence, 1979: 93 (as James Minor)

1980

Zeri, Federico, and Elizabeth E. Gardner. Italian Paintings: Sienese and Central Italian Schools. A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 1980: 95.

1982

Natale, Mauro, Alessandra Mottola Molfino, and Joyce Brusa. Museo Poldi Pezzoli. Vol. 1 (of 7), Dipinti. Milan, 1982: 145.

1985

European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1985: 374, repro.

1987

Previtali, Giovanni. "Problems in the Workshop of Simone Martini." Center, Research Reports and Record of Activities 7 (1987): 83-84, repro.

1988

Boskovits, Miklós, ed. Frühe italienische Malerei: Gemäldegalerie Berlin, Katalog der Gemälde. Translated by Erich Schleier. Berlin, 1988: 75.

Martindale, Andrew. Simone Martini. Oxford, 1988: 35 n. 18.

Previtali, Giovanni. "Introduzione ai problemi della bottega di Simone Martini." In Simone Martini: atti del convegno; Siena, March 27-29, 1985. Edited by Luciano Bellosi. Florence, 1988: 166 n. 23

1990

Boskovits, Miklós. "Review of Simone Martino by Andrew Martindale." Kunstchronik 43 (1990): 600.

1991

De Benedictis, Cristina. "Lippo Memmi." In Enciclopedia dell’arte medievale. Edited by Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana. 12 vols. Rome, 1991-2002: 7(1996):732.

Christie, Manson & Woods. Important Paintings by Old Masters. New York, 11 January 1991: 28.

1995

Baetjer, Katharine. European Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art by Artists Born before 1865. A Summary Catalogue. New York, 1995: 42.

1998

Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Prague, 1998: 205.

Kier, Hiltrud, and Frank Günter Zehnder, eds. Lust und Verlust. Vol. 2 (of 2), Corpus-Band zu Kölner Gemäldesammlungen 1800-1860. Cologne, 1998: 552, repro.

1999

Bagnoli, Alessandro. La Maestà di Simone Martini. Cinisello Balsamo (Milan), 1999: 156 n. 24, 179.

2009

Bellosi, Luciano, et al., eds. La collezione Salini: dipinti, sculture e oreficerie dei secoli XII, XIII, XIV e XV. 2 vols. Florence, 2009, 2015: 1(2009):135, repro. 139.

2016

Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. The Systematic Catalogue of the National Gallery of Art. Washington, 2016: 351-369, color repro.

Inscriptions

on the left of the Saint: .SAN[C]TVS.; on the right of the Saint: TAD[D]EVs.

Wikidata ID

Q20173002