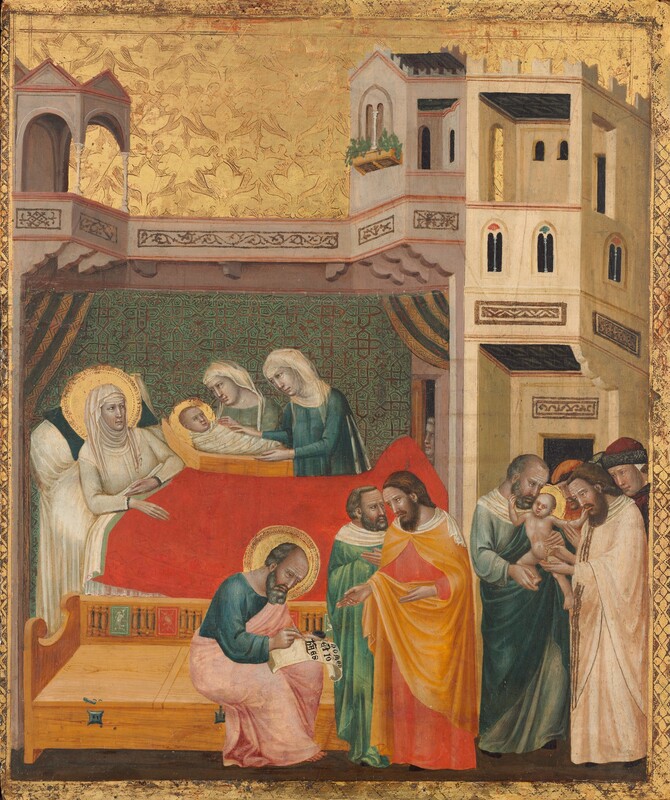

The Birth, Naming, and Circumcision of Saint John the Baptist

c. 1335

Giovanni Baronzio

Painter, Italian, active c. 1320 - 1350

This panel, along with The Baptism of Christ and Madonna and Child with Five Angels were once part of the same altarpiece devoted to Saint John the Baptist (see Reconstruction). Several more components have found their way to other collections. The altarpiece’s original location is not known, though it was probably featured in a church dedicated to the saint in what is today the northern Italian region Emilia-Romagna, close to Baronzio’s home in Rimini. No documents pertaining to the altarpiece have ever been found. It must have been dismantled by the mid-19th century, when pieces of it began to appear on the art market. The dispersed parts have been linked to each other through various clues: similar dimensions, related subject matter, the artist’s style, and particular details of technique and execution. One of those is the brocade pattern that has been incised into the gold background, which appears in all the panels. Another clue is the small punch used to impress a pattern in the gold of the halos.

Giovanni Baronzio seems to have delighted in filling his works with activity and a wealth of everyday details. Here, he crowds three episodes from the life of John the Baptist into one busy scene. They unfold in an elaborate architectural setting with loggias and a flower box sprouting vegetation. At the left, John’s mother, Elizabeth, rests while two women attend to the newborn baby. As was the custom in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the infant is immobilized in swaddling clothes. Another figure, almost hidden, peers in from the doorway. Below this group, John’s father, Zacharias, writes the baby’s name on a scroll. At that moment he miraculously regained the power of speech, which had been taken from him as punishment for doubting an angel’s announcement that he and Elizabeth, both elderly, would have a child. A witness to the naming looks to the right, leading our eyes to a third scene. There, the recalcitrant infant John stands above the circumciser’s knife, which has drawn blood—a sign of the covenant between God and the people of Israel.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 1

Artwork overview

-

Medium

tempera on panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

painted surface: 46.4 × 38.3 cm (18 1/4 × 15 1/16 in.)

overall: 48.8 × 40.7 cm (19 3/16 × 16 in.)

framed: 55.7 x 48.1 x 5.1 cm (21 15/16 x 18 15/16 x 2 in.) -

Accession Number

1952.5.68

Associated Artworks

The Baptism of Christ

Giovanni Baronzio

1335

Madonna and Child with Five Angels

Giovanni Baronzio

1335

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Possibly commissioned as part of the high altarpiece of a church dedicated to Saint John the Baptist in Emilia Romagna or in the Marche, Italy. George Edmund Street [1824-1881], London, by 1880;[1] probably by inheritance to his son, Arthur Edmund Street [1855-1938], Bath. Harold Irving Pratt [1877-1939], New York, by 1917.[2] (Wildenstein & Co., Inc., London, New York and Paris); sold 1947 to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation;[3] gift 1952 to NGA.

[1] The painting must have been acquired by Street, the English Gothic Revival architect, together with two other fragments from the same dismantled altarpiece: the Annunciation of the Baptist’s Birth and the Baptist Sending His Disciples to Christ. In addition to the Gallery’s painting, these two panels were also exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1880 (nos. 231 and 234). Both were presented anew at an exhibition in Bristol in 1937 as the property of Street’s son in Bath. But since then all trace of them has been lost: it is possible these two were destroyed in a bombardment that struck the Street family’s house during World War II; see Richard Offner, A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. III, vol. V, The Fourteenth Century. Bernardo Daddi and his circle (Brattleboro, 1947), 2nd edition: Miklós Boskovits, assisted by Ada Labriola and Martina Ingedaay Rodio, Florence, 2001: 472, citing information provided by Federico Zeri. The date of Street’s acquisition of the panels is uncertain; perhaps it occurred between the dates of the first and second edition of his book Brick and Marble in the Middle Ages. Notes of a Tour in the North of Italy, London, 1855 (Brick and Marble in the Middle Ages. Notes of Tours in the North of Italy, London, 1874). In the first edition the author shows little interest in painting, but in the preface to the second he recalls his many visits to Italy and draws the reader’s attention to the publication of James Archer Crowe and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, A New History of Painting in Italy from the Second to the Sixteenth Century, London, 1864-1871.

[2] Exactly when the panel passed into the collection of Pratt, the American oil industrialist and philanthropist, is also uncertain. Reports of this collection are found from 1909 onward (see Edward Fowles, Memories of Duveen Brothers, London, 1976: 33). Pratt lent the painting to a 1917 exhibition at Kleinberger Galleries in New York, from whom he possibly acquired it. By the time of the 1947 exhibition of Italian paintings at Wildenstein's in New York, it was no longer in the Pratt collection: the catalogue lists the owner as Wildenstein.

[3] The bill of sale (copy in NGA curatorial files) from Wildenstein & Co. to the Kress Foundation for thirteen paintings and one tapestry room is dated 30 October 1947; payment was made in installments. The painting is described as by Giovanni Baronzio da Rimini. See also The Kress Collection Digital Archive, https://kress.nga.gov/Detail/objects/1926.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1880

Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters, and by Deceased Masters of the British School. Winter Exhibition, Royal Academy, London, 1880, no. 228, as Birth of St. John the Baptist by an unknown artist.

1917

A Loan Exhibition of Italian Paintings, Kleinberger Galleries, New York, 1917, no. 70, repro., as by Giovanni Baronzio.

1947

Italian Paintings, Wildenstein & Co., Inc., New York, 1947, no. 37, repro., as by Giovanni Baronzio.

1995

Il Trecento Riminese: Maestri e botteghe tra Romagna e Marche, Museo della Città, Rimini, Italy, 1995-1996, no. 51, repro.

Bibliography

1916

Sirén, Osvald. "Giuliano, Pietro and Giovanni da Rimini." The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 29 (1916): 320, 321 pl. VI.

1917

Sirén, Osvald, and Maurice W. Brockwell. Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Italian Primitives. Exh. cat. F. Kleinberger Galleries. New York, 1917: 180 (repro.), 181.

1924

Offner, Richard. "A Remarkable Exhibition of Italian Paintings." The Arts 5 (1924): 245.

1925

McCormick, William B. "Otto H. Kahn Collection." International Studio 80 (1925): 282, 286.

1931

Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. Milan, 1931: no. 94, repro.

1932

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford, 1932: 44.

1933

Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. Translated by Countess Vanden Heuvel and Charles Marriott. 3 vols. New York and Milan, 1933: 1:no. 116, repro.

1935

Salmi, Mario. "La scuola di Rimini, 3." Rivista del R. Istituto d'archeologia e storia dell’arte 5 (1935): 112, repro. 113.

1936

Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del rinascimento: catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opere con un indice dei luoghi. Translated by Emilio Cecchi. Milan, 1936: 38.

Brandi, Cesare. "Conclusioni su alcuni discussi problemi della pittura riminese del Trecento." Critica d’arte 1 (1936): 231 n. 18, 236-237.

Salmi, Mario. "Review of Conclusioni su alcuni discussi problemi della pittura riminese del Trecento by Cesare Brandi." Rivista d’arte 18 (1936): 413.

1940

Falk, Ilse. "Studien zu Andrea Pisano." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Zurich, 1940: 128.

1941

Coletti, Luigi. I Primitivi. 3 vols. Novara, 1941-1947: 3(1947):xviii, lxix n. 34, pl. 34.

1947

Frankfurter, Alfred M. "How Modern the Renaissance." Art News 45 (1947): repro. 17.

Italian Paintings. Exh. cat. PaceWildenstein, New York, 1947: n.p., no. 37, repro.

1951

Paintings and Sculpture from the Kress Collection Acquired by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation 1945-1951. Introduction by John Walker, text by William E. Suida. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1951: 36, no. 6, repro., as Birth, Naming and Circumcision of St. John the Baptist.

Toesca, Pietro. Il Trecento. Storia dell’arte italiana, 2. Turin, 1951: 730-731.

1954

Suida, Wilhelm. European Paintings and Sculpture from the Samuel H. Kress Collection. Seattle, 1954: 14.

1957

Exposition de la Collection Lehman de New York. Exh. cat. Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, 1957: 31-32.

1959

Paintings and Sculpture from the Samuel H. Kress Collection. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1959: 24, repro.

1965

Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 86.

Volpe, Carlo. La pittura riminese del Trecento. Milan, 1965: 38-39, 80, fig. 182.

1966

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools, XIII-XV Century. London, 1966: 68-69, fig. 183.

1967

Klesse, Brigitte. Seidenstoffe in der italienischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Bern, 1967: 64, 186-187, 281.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 75, repro.

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance. Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London, 1968: 1:362.

1970

Seymour, Charles. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven and London, 1970: 108.

1972

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass., 1972: 130, 416, 647.

1975

European Paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1975: 222, repro.

Szabó, George. The Robert Lehman Collection: A Guide. New York, 1975: 25.

1978

Kaftal, George, and Fabio Bisogni. Saints in Italian Art. Vol. 3 (of 4), Iconography of the Saints in the Painting of North East Italy. Florence, 1978: 512, 514.

1979

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Catalogue of the Italian Paintings. National Gallery of Art. 2 vols. Washington, 1979: 1:317-318; 2:pl. 227.

Zuliani, Fulvio. "Tommaso da Modena." In Tomaso da Modena: catalogo. Edited by Luigi Menegazzi. Exh. cat. Convento di Santa Caterina, Capitolo dei Dominicani, Treviso, 1979: 105 n. 9.

1982

Christiansen, Keith. "Fourteenth-Century Italian Altarpieces." Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art 40 (1982): 42, repro. 44.

1985

European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1985: 255, repro.

1986

Castelnuovo, Enrico, ed. La Pittura in Italia. Il Duecento e il Trecento. Essays by Andrea Bacchi and Daniele Benati. 2 vols. Milan, 1986: 1:208; 2:611.

1987

Pope-Hennessy, John, and Laurence B. Kanter. The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings. New York, 1987: 86, repro. 288.

1989

"Maestro della Vita del Battista." In Dizionario della pittura e dei pittori. Edited by Enrico Castelnuovo and Bruno Toscano. 6 vols. Turin, 1989-1994: 3(1992):430.

1990

Pasini, Pier Giorgio. La pittura riminese del Trecento. Cinisello Balsamo (Milan), 1990: repro. 124.

1991

Benati, Daniele. "Baronzio, Giovanni." In Enciclopedia dell’arte medievale. Edited by Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana. 12 vols. Rome, 1991-2002: 3(1992):121.

Freuler, Gaudenz, ed. Manifestatori delle cose miracolose: arte italiana del ’300 e ’400 da collezioni in Svizzera e nel Liechtenstein. Exh. cat. Villa Favorita, Fondazione Thyssen-Bornemisza, Lugano-Castagnola. Einsiedeln, 1991: 132.

1992

Mancinelli, Fabrizio. "I dipinti della Pinacoteca dall’XI al XV secolo." In Pinacoteca Vaticana: nella pittura l’espressione del messaggio divino nella luce la radice della creazione pittorica. Edited by Umberto Baldini. Milan, 1992: 162-163.

1993

Boskovits, Miklós. "Per la storia della pittura tra la Romagna e le Marche ai primi del ’300." Arte cristiana 81 (1993): 168-169.

1994

Rossi, Francesco. Catalogo della Pinacoteca Vaticana, 3. Il Trecento: Umbria, Marche, Italia del Nord. Vatican City, 1994: 113-118, fig. 153.

1995

Baetjer, Katharine. European Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art by Artists Born before 1865. A Summary Catalogue. New York, 1995: 110.

Benati, Daniele, ed. Il Trecento riminese: Maestri e botteghe tra Romagna e Marche. Essays by Daniele Benati and Alessandro Marchi. Exh. cat. Museo della città, Rimini. Milan, 1995: 47, 55, 56 n. 3, 116, 248, 260, 264, 266, repro. 267-268.

1996

Tambini, Anna. "In margine alla pittura riminese del Trecento." Studi romagnoli 47 (1996): 466.

2002

Ragionieri, Giovanna. "Baronzio, Giovanni." In La pittura in Europa. Il Dizionario dei pittori. Edited by Carlo Pirovano. 3 vols. Milan, 2002: 1:53.

2005

Laclotte, Michel, and Esther Moench. Peinture italienne: Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon. Paris, 2005: 63.

2006

Benati, Daniele. "Il Dossale Corvisieri nel percorso di Giovanni Baronzio." L’Arco 4 (2006): 27.

Morozzi, Luisa. "Da Lasinio a Sterbini: ‘primitivi’ in una raccolta romana di secondo Ottocento." In AEIMNEΣTOΣ. Miscellanea di studi per Mauro Cristofani. 2 vols. Edited by Benedetta Adembri. Florence, 2006: 2:912, 916 n. 50.

2008

Ferrara, Daniele, ed. Giovanni Baronzio e la pittura a Rimini nel Trecento. Exh. cat. Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome. Cinisello Balsamo (near Milan), 2008: repro. 29, 31, 106.

2016

Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. The Systematic Catalogue of the National Gallery of Art. Washington, 2016: 159-175, color repro.

Inscriptions

on the sheet on which Zacharias is writing: NOMEN / E[S]T IO / HA[NN]ES (The name is John)

Wikidata ID

Q20173104