Country House in a Park

c. 1675

Jacob van Ruisdael

Artist, Dutch, c. 1628/1629 - 1682

Jacob van Ruisdael represents the pinnacle of seventeenth-century Dutch landscape painting. This great artist, the son of a painter and the nephew of Salomon van Ruysdael (see NGA 2007.116.1), began his career in Haarlem but moved to Amsterdam in about 1656. His long and productive career yielded a wide variety of landscape scenes that reflect Ruisdael’s vision of the grandeur and powerful forces of nature.

Depictions of elegant country houses came into vogue in the latter half of the seventeenth century as increasing numbers of wealthy Dutch merchants built homes along the river Vecht and in other picturesque locations in the Dutch Republic. Yet not all of these seemingly accurate representations portray real structures; sometimes the scenes were purely imaginary, intended to project an ideal of country existence rather than its actuality. In this painting, Ruisdael, who depicted views of country houses only at the end of his career, either created an imaginary view of a country estate or superimposed the existing town home of a patron onto this scene of a wilderness garden. The house, with a yellow façade articulated by pilasters, a stringcourse, and a balustrade, would be very much at home on the bank of an Amsterdam canal.

The garden seems to be an artistic invention as well. The natural and artificial components of Ruisdael’s garden are enjoyed by the various groups of people who amble about. An elaborate fountain, surmounted by a small sculpted figure of a boy, is counterbalanced by an even more dramatic fountain in the right center. Just beyond, two figures gesture in surprise as they are startled by the water from a trick fountain spurting up around them. The soaring Norwegian spruces, exotic specimens native to Scandinavia that had been used in Dutch gardens since at least the 1640s, provide visual depth as well as striking contrasts with the cloudy sky.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 76.3 x 97.5 cm (30 1/16 x 38 3/8 in.)

framed: 98.4 x 118.4 x 6.7 cm (38 3/4 x 46 5/8 x 2 5/8 in.) -

Accession Number

1960.2.1

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Savile family, Rufford Abbey, Nottinghamshire, possibly Sir John Savile, 1st baron Savile [1818-1896], or his nephew John Savile Savile-Lumley, 2nd baron Savile [1853-1931]; the latter's son, George Halifax Lumley-Savile, 3rd baron Savile [1919-2008], Rufford Abbey; (Savile family sale, Christie, Manson & Woods, London, 18 November 1938, no. 123); Rupert L. Joseph [d. 1959], New York;[1] bequest 1960 to NGA.

[1] Labels on the stretcher indicate that the painting was lent by Mr. Joseph to the Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, in 1942 and the Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1948. The loan to the museum in Springfield lasted at least until 1955; see the letter of 23 May 1955 from Frederick B. Robinson, director of the museum, to Mr. Joseph, to which was attached a list of the objects currently on loan from the collector (Rupert L. Joseph Papers, MssCol 1598, Manuscripts and Archives DIvision, New York Public Library: box 2, folder 1; copy in NGA curatorial files).

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1942

Loan to display with permanent collection, Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, 1942-1948.

1948

Loan to display with permanent collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, Massachusetts, 1948-1955.

1981

Jacob van Ruisdael, Mauritshuis, The Hague; Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1981-1982, no. 54.

1996

Obras Maestras de la National Gallery of Art de Washington, Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City, 1996-1997, unnumbered catalogue, color repro.

Bibliography

1907

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. Beschreibendes und kritisches Verzeichnis der Werke der hervorragendsten holländischen Maler des XVII. Jahrhunderts. 10 vols. Esslingen and Paris, 1907-1928: 4(1911):xxxxx, no. 819.

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. 8 vols. Translated by Edward G. Hawke. London, 1907-1927: 4(1912):256, no. 819.

1928

Rosenberg, Jakob. Jacob van Ruisdael. Berlin, 1928: 67, no. 520.

1964

Gorissen, Friedrich. _ Conspectus Cliviae. Die klevische Residenz in der Kunst des 17. Jahrhunderts_. Kleve, 1964: under no. 62.

1965

Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 119.

1967

Dattenberg, Heinrich. Niederrheinansichten holländischer Künstler des 17. Jahrhunderts. Die Kunstdenkmäler des Rheinlands 10. Düsseldorf, 1967: 283, no. 312.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 106, repro.

1975

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1975: 294, no. 392, repro.

National Gallery of Art. European paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. Washington, 1975: 316, repro.

1981

Slive, Seymour, and Hans Hoetink. Jacob van Ruisdael. Exh. cat. The Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis, The Hague; The Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. New York, 1981: no. 54.

Schmidt, Winfried. Studien zur Landschaftskunst Jacob van Ruisdaels: Frühwerke und Wanderjahre. Hildesheim, 1981: 75, pl. 22.

1984

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 295, no. 385, color repro.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 364, repro.

1991

Walford, E. John. Jacob van Ruisdael and the Perception of Landscape. New Haven, 1991: 167-168, repro.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 345-348, color repro. 347.

1996

Ortiz Hernán, Elena, and Octavio Hernández R. Obras maestras de la National Gallery of Art. Translated by Bertha Ruiz de la Concha. Exh. cat. Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City, 1996: 72-73, repro.

2001

Slive, Seymour. Jacob van Ruisdael: A Complete Catalogue of his Paintings, Drawings and Etchings. New Haven, 2001: 417, no. 588.

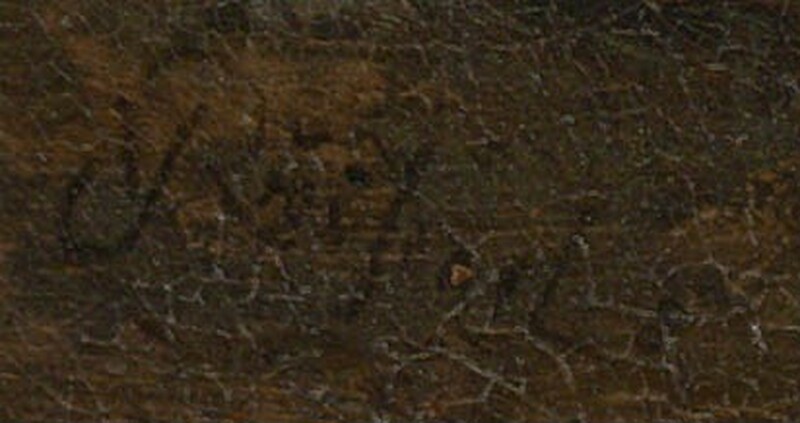

Inscriptions

lower left: J v Ruisdael (JvR in ligature)

Wikidata ID

Q20177647