Still Life with Flowers and Fruit

c. 1715

Jan van Huysum

Painter, Dutch, 1682 - 1749

Jan van Huysum’s lasting fame centers on his exuberant arrangements and technical virtuosity. More than any other artist before or after, he was able to capture the dynamic energy of a profuse array of flowers and fruit. In this superb and large example, the bouquet fills the entire panel. Flowers overflowing their terra-cotta vase and peaches and grapes spilling over the foreground ledge create a sense of opulent abundance. Woven in and out of the densely packed bouquet of peonies, roses, carnations, and auriculae are the rhythmically flowing stems and blossoms of tulips, veronica, tuberoses, and hops. The artist masterfully integrated insects into his bouquet and suggested the translucence of dewdrops on petals and leaves. He often illuminated blossoms situated at the back of his bouquets and silhouetted darker foreground leaves and tendrils against them.

Van Huysum was reportedly secretive about his technique, and he apparently forbade anyone, including his own brothers, to enter his studio for fear that they would learn how he purified and applied his colors. He spent a portion of each summer in Haarlem, already a major horticultural center in his day, in order to study flowers in bloom. The remarkable similarities in the shapes and character of individual blossoms in different still-life paintings indicate, however, that he also used drawn or painted models to satisfy pictorial demands.

Trained by his father, Justus van Huysum the Elder (1659–1716), Jan derived his compositional ideas and technical prowess from the examples of Jan Davidsz de Heem (1606–1684) and Willem van Aelst (1626–1683). Following De Heem’s lead, Jan van Huysum organized his bouquets with sweeping rhythms that draw the eye in circular patterns throughout the composition and included flowers that do not bloom at the same time. Van Aelst’s work showed Van Huysum the advantages of massing brightly lit flowers in order to focus the dynamically swirling rhythms underlying his compositions.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 50

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on panel

-

Credit Line

Patrons' Permanent Fund and Gift of Philip and Lizanne Cunningham

-

Dimensions

overall: 78.7 x 61.3 cm (31 x 24 1/8 in.)

framed: 104.1 x 86.4 x 7.6 cm (41 x 34 x 3 in.) -

Accession Number

1996.80.1

More About this Artwork

Article: A Fashionable Spin on Spring in Art

Social media influencer Holly Pan's fashion-forward visit to National Gallery spaces that remind her of spring.

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Baron Louis de Rothschild [1882-1955], Vienna.[1] his niece, Baroness Reininghaus [née Bettina Rothschild Springer, 1912-1974]; her husband, Baron Kurt Reininghaus [d. 1984]; sold to (Galerie Sanct Lucas, Vienna); sold c. 1994 to Mr. and Mrs. Philip Cunningham, Alexandria, Virginia; partially sold and partially given 1996 through (Otto Naumann, New York) to NGA.

[1] This painting was confiscated by the Nazis from the Louis de Rothschild collection in Vienna in 1938 and was destined for Adolf Hitler's planned museum in Linz, Austria. It is listed on the 20 October 1939 Vorschlag sur Verteilung der in Wien beschlagnahmte Gemaelde: Für das Kunstmuseum in Linz prepared by Hitler's curator, Hans Posse, and also Posse's Verzeichnis der für Linz in Aussicht genommenen Gemälde dated 31 July 1940 (OSS Consolidated Interrogation Report #4, Linz: Hitler's Museum and Library, 15 December 1945, Attachments 72 and 73, U.S. National Archives RG226/Entry 190B/Box 35, copy in NGA curatorial files). The records of the Allies' Munich Central Collecting Point indicate that the painting was recovered by the Allies and restituted to Austria on 11 May 1948. It was returned to Louis de Rothschild in 1949 (Munich property card #1665; Austrian Receipt for Cultural Property dated 11 May 1948; copies in NGA curatorial files.). The painting is listed and illustrated in Birgit Schwarz, Hitlers Museum: Die Fotoalben Gemäldegalerie Linz: Dokumente zum “Führermuseum”, Vienna, 2004: no. V/1. See also Sophie Lillie, Was Einmal War, Vienna, 2003: 113-116.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1999

From Botany to Bouquets: Flowers in Northern Art, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1999, no. 19, fig. 60.

2000

Art for the Nation: Collecting for a New Century, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2000-2001, unnumbered catalogue, repro.

2006

The Temptations of Flora: Jan van Huysum 1682-1749 (De verleiding van Flora: Jan van Huysum 1682-1749), Stedelijk Museum Het Prinsenhof, Delft; The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2006-2007, no. F5, repro.

Bibliography

1999

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. From Botany to Bouquets: Flowers in Northern Art. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1999: 67-69, 71, 84, no. 19, fig. 60.

2000

National Gallery of Art. Art for the Nation: Collecting for a New Century. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2000: 38-39, 304, color repro.

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. The Golden Age of Dutch and Flemish painting: the Edward and Sally Speelman Collection. Exh. cat. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague. Houston, 2000: 50-51, repro.

2004

Hand, John Oliver. National Gallery of Art: Master Paintings from the Collection. Washington and New York, 2004: 212-213, no. 171, color repro

2006

Segal, Sam, Mariël Ellens, and Joris Dik. De verleiding van Flora: Jan van Huysum, 1682-1749. Exh. cat. Museum het Prinsenhof, Delft; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Zwolle, 2006: no. 5, repro.

2007

Segal, Sam. The Temptations of Flora: Jan van Huysum, 1682-1749. Translated by Beverly Jackson. Exh. cat. Museum Het Prinsenhof, Delft; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Zwolle, 2007: no. 5, repro.

Inscriptions

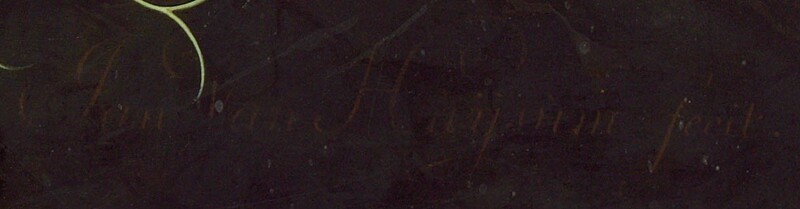

lower right: Jan Van Huysum fecit

Wikidata ID

Q20177776