Language

On this Page:

Overview

In what ways was the US settled and unsettled in the 19th century?

What role did artists play in shaping public understandings of the US West?

When you think about the US West, what images and stories come to mind?

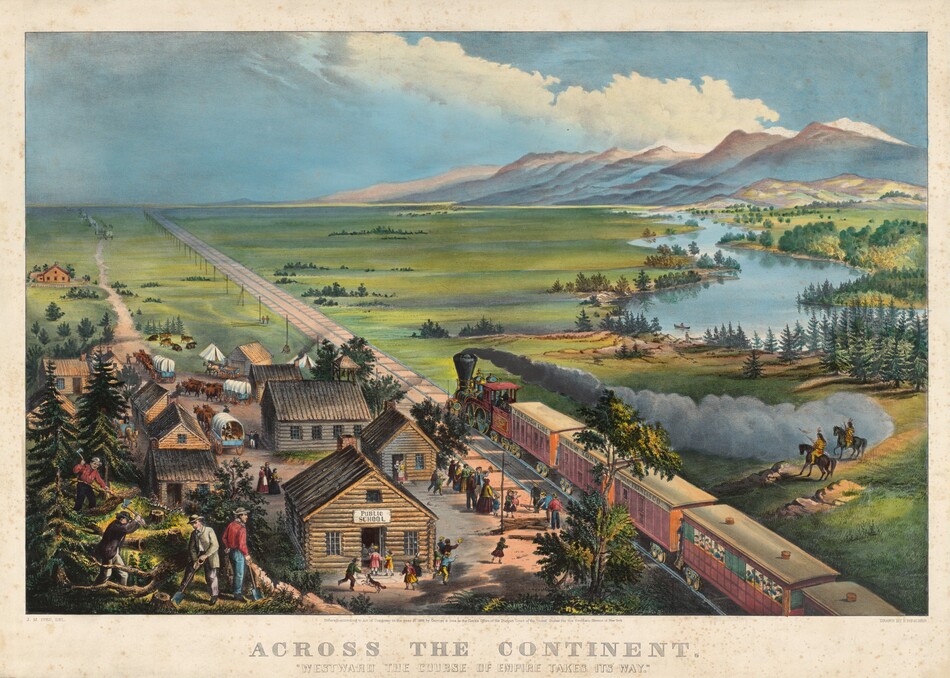

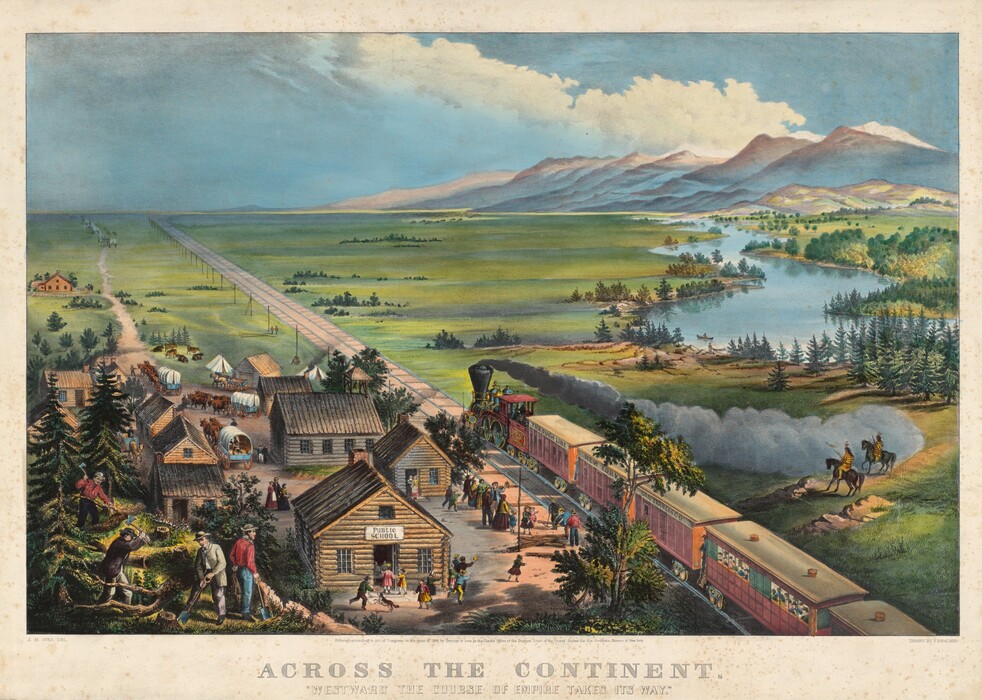

Across the Continent: “Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way” shows a vision of settling the United States that in many ways still resonates today.

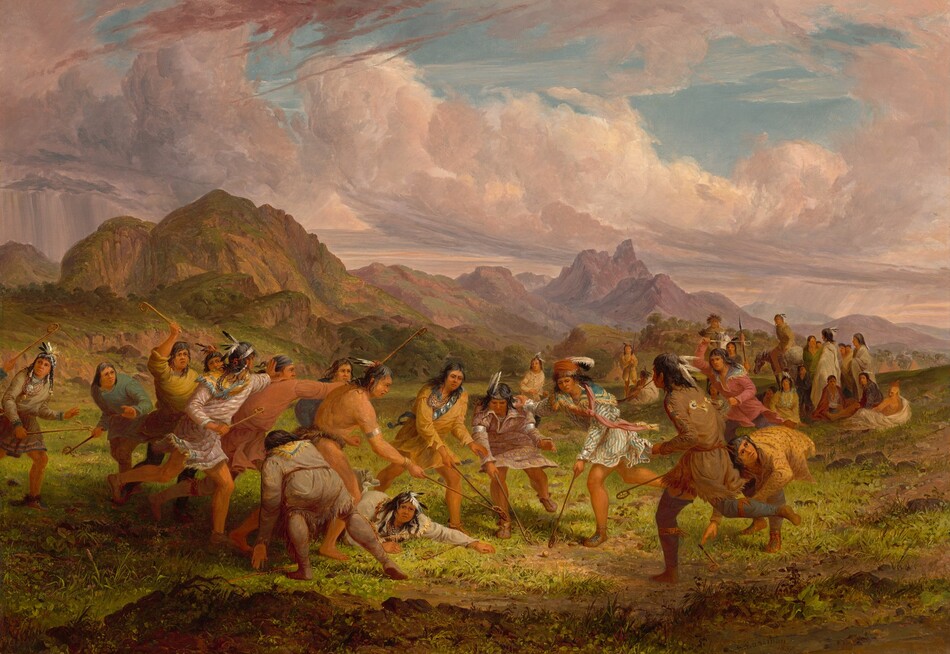

A wagon train of settlers; expansive, empty lands; evidence of the concept of “progress”—these elements appear again and again in works of art and other media in the 19th century. Together these elements illustrate the idea of manifest destiny, a belief (held by some) that expansion of the US westward toward the Pacific Ocean was destined and justified. Across the Continent helped perpetuate this narrative among people who purchased and saw the print. Westward expansion was not inevitable, though, nor was it necessarily easy or pleasant for those who were impacted by the country’s rapid growth.

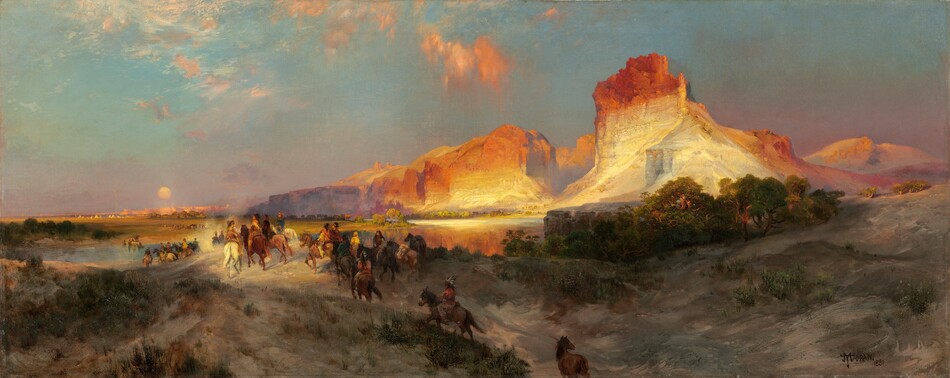

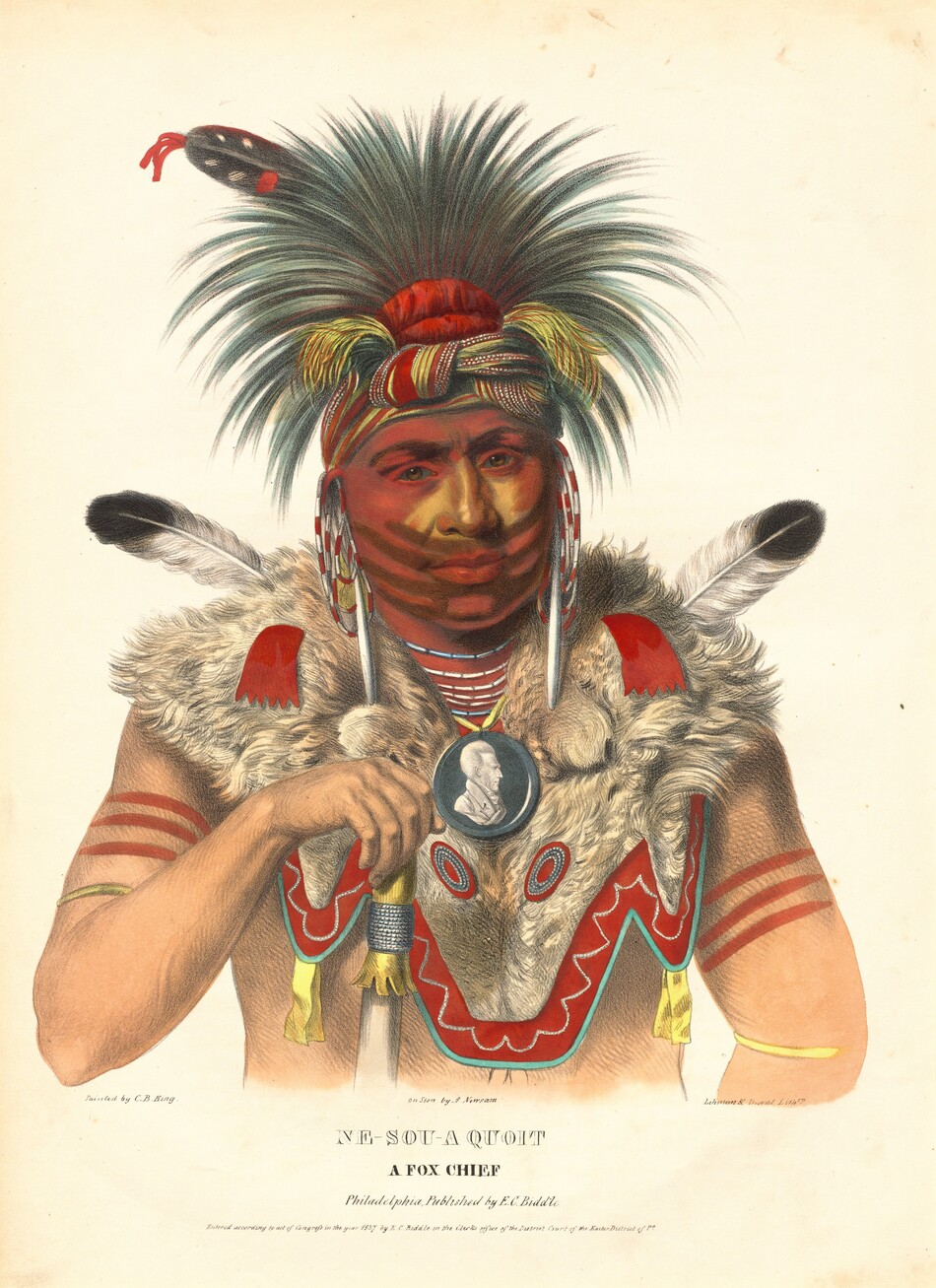

The United States paid $15 million to France in 1803 for lands that doubled the size of the country in what many have called the “real estate deal of the century,” the Louisiana Purchase. Yet France, and Spain before it, did not have actual legal rights to the land other than claims they asserted through colonial conquest. By purchasing rights to the territory of Louisiana—stretching from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains—from France, the United States averted fights with the Spanish or French, but precipitated conflict with the hundreds of Native nations who lived in those lands.The Indian Removal Act of 1830, passed during President Andrew Jackson’s tenure, established treaty making as the main mechanism for relocating indigenous peoples to make way for primarily white settlers. However, when tribes refused to sign treaties and leave their ancestral homelands, Jackson ignored legislation and ordered troops to forcibly relocate people. Thousands of people were killed during death marches, including members of the Muscogee (Creek), Chahta (Choctaw), Aniyunwiya (Cherokee), Chikasha (Chickasaw), Seminole, and Potawatomi nations. Even more were decimated by disease, including the Mandan. Others fought back or resisted, like the Seminole, Lakota, and Diné (Navajo) nations. In general, tribes across the country relocated, voluntarily or not, as settlers and new immigrants claimed land.

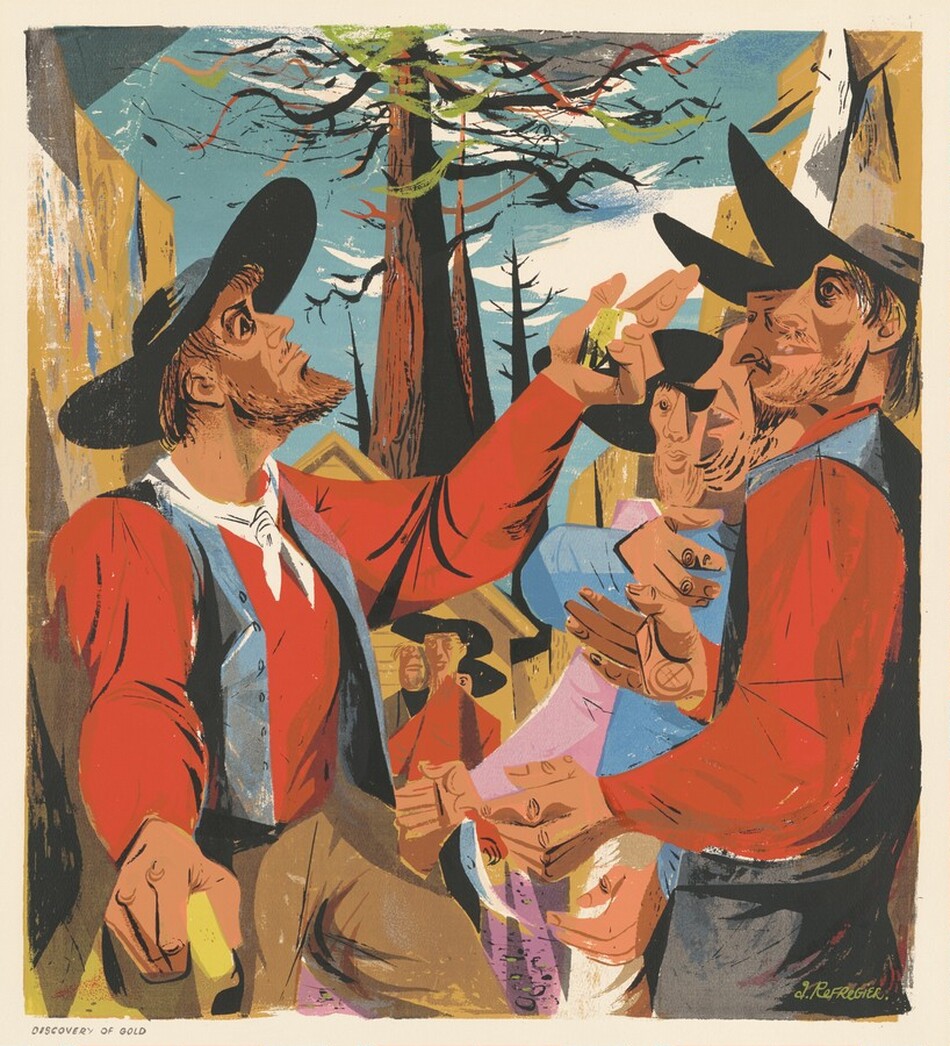

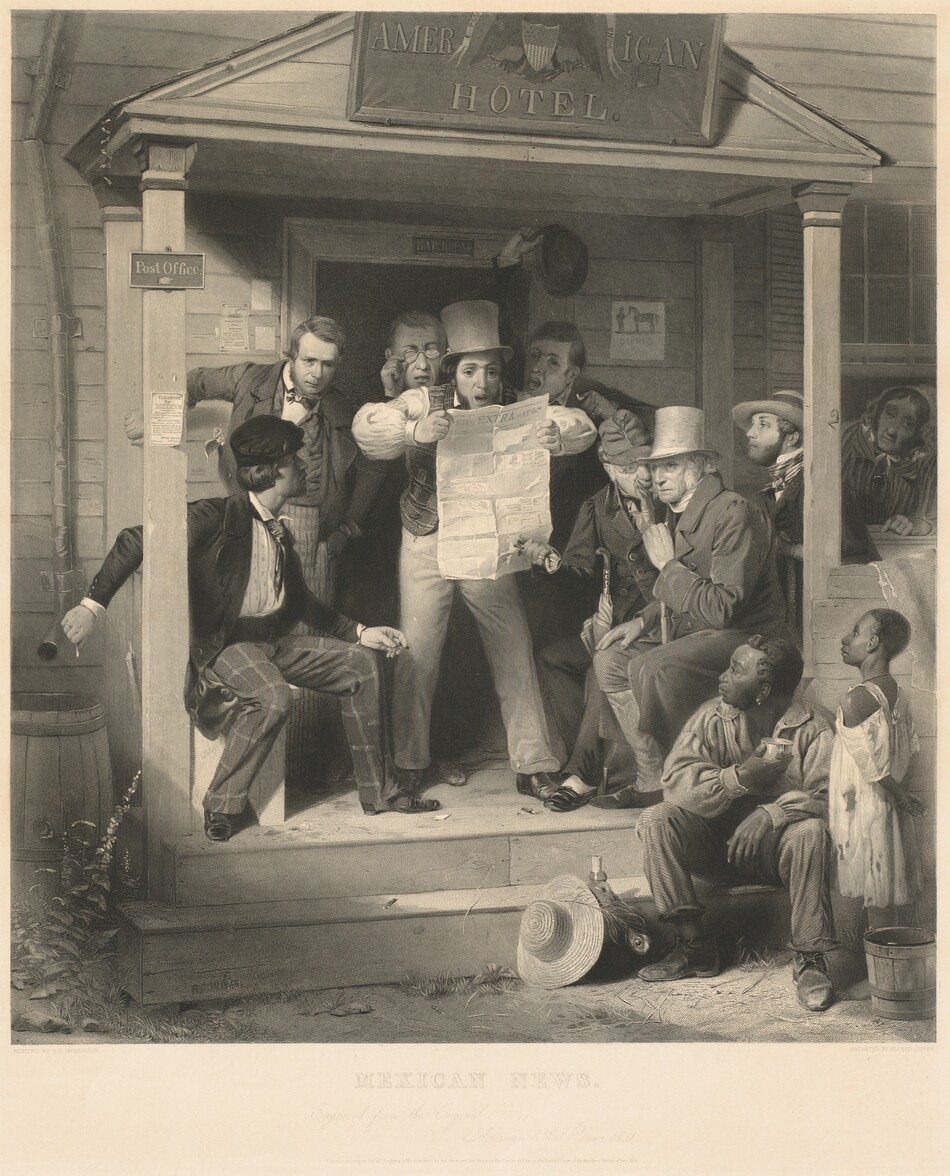

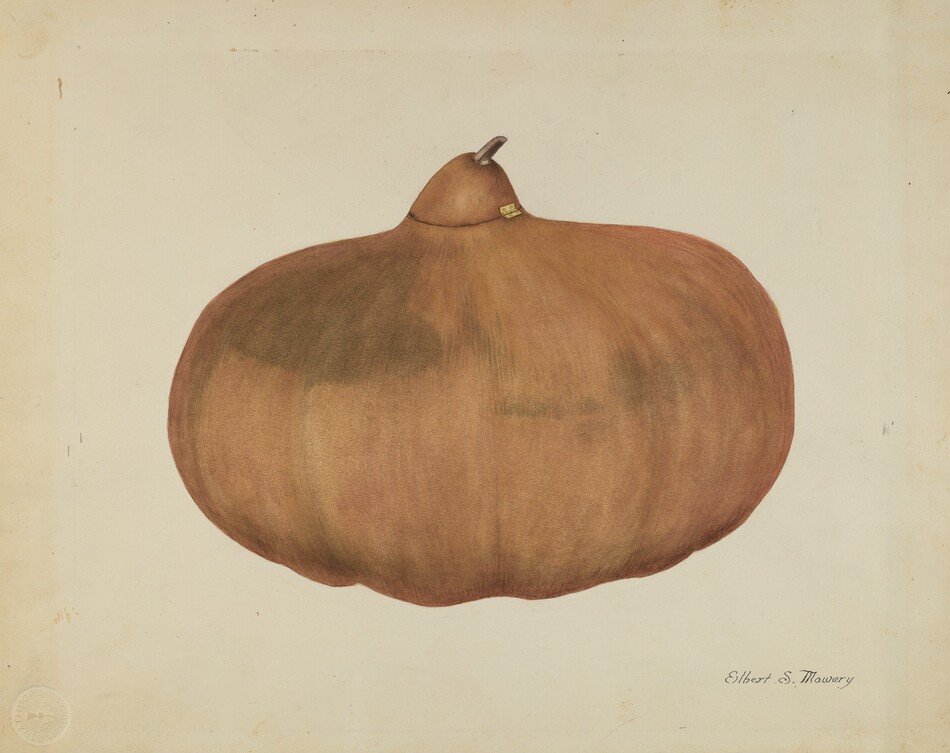

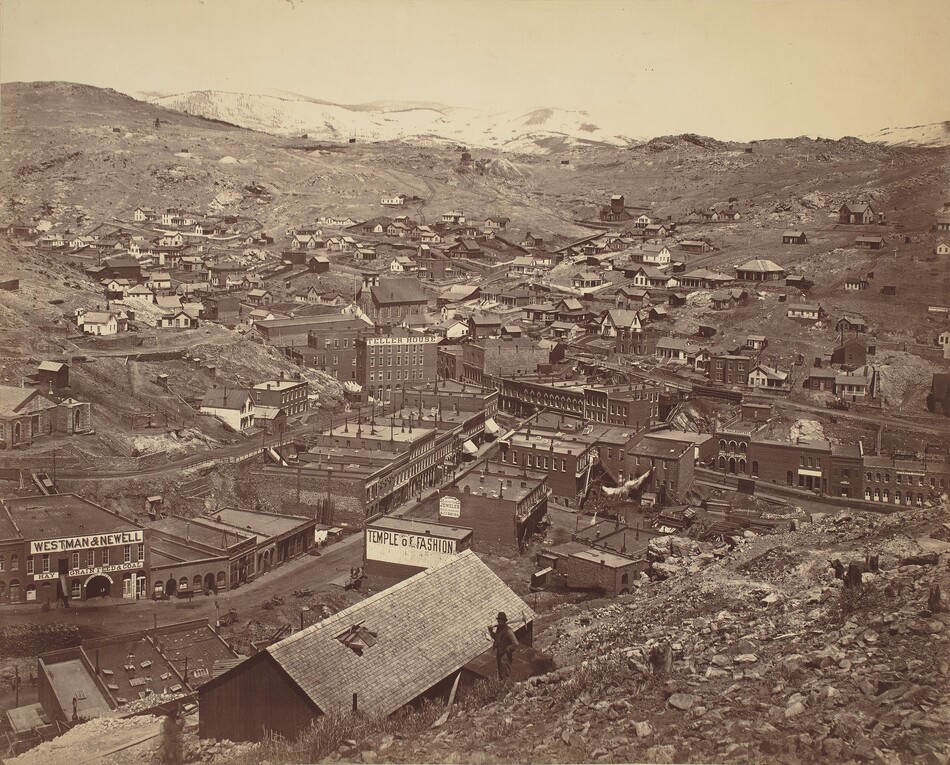

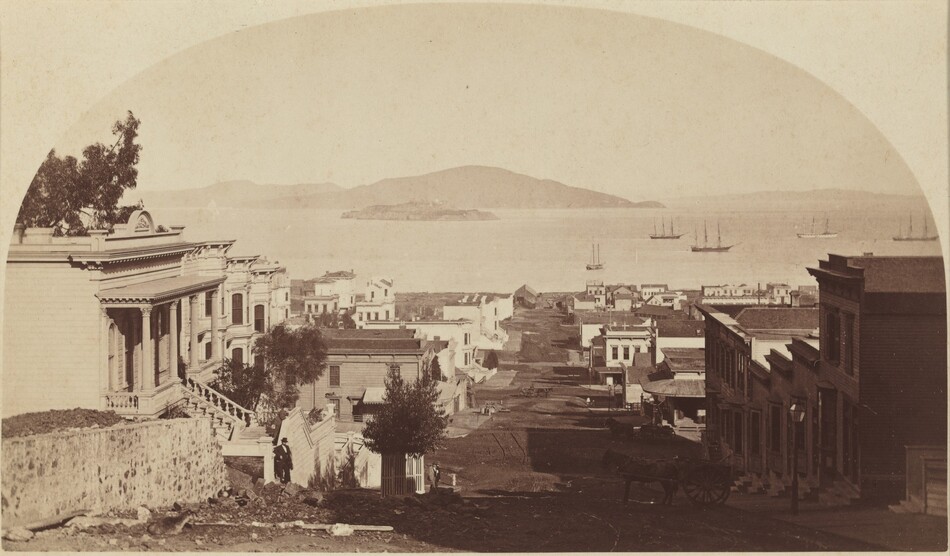

Other people also inhabited the US West in the 19th century. French Canadian traders and Spanish colonists and missionaries had arrived centuries earlier. When gold was discovered in California in 1848, news spread quickly and immigrants from around the world rushed to San Francisco, including thousands of Chinese migrants who sailed across the Pacific. Both freed and enslaved Africans and African Americans also lived throughout the West; the Compromise of 1850 admitted both slave and free states after new territory was acquired in the US–Mexican War.

There is no single story of the West. Whose perspectives, experiences, and cultures are visible and represented in the works of art in this module? Whose stories are left out or marginalized? And what more might we need to find out?

Selected Works

Activity: Point of View Narratives

Invite individuals or small groups of students to examine reproductions of Across the Continent: “Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way.” Ask them to identify the characters in the work, the setting, and what story is being communicated. Share with them that the artist was a British immigrant who never visited the West, and that the print’s audience was likely white European Americans living in the Eastern United States. Then, introduce one of the books listed below or tell a story about a specific indigenous nation’s experience with US settlement.

- Brian Floca, Locomotive (New York: Atheneum Books, 2013)

- Julius Lester and Jerry Pinkney, Black Cowboys, Wild Horses (New York: Dial Books, 1998)

- Louise Erdrich, The Birchbark House (New York: Disney-Hyperion, 2002)

- Sherry Garland, Valley of the Moon: The Diary of María Rosalia de Milagros (New York: Scholastic, 2001)

After reading or hearing the story, identify areas of inaccuracy or exaggeration in Across the Continent with students. What changes do they suggest for the picture? Whose perspectives should be included in the story? Ask them to write or create a new story from a single point of view. What would they see, hear, feel, and experience? Alternatively, students could modify or create a new version of Across the Continent using art materials or perform a dramatic story as a small group.

Encourage students to develop a new title or headline for their story or work of art after it’s completed.

Activity: Developing Cultural Awareness

Do you call the United States home? Research which indigenous peoples lived where you do prior to colonization. Do they still live there? If not, under what circumstances did they leave? What kinds of interactions did they have with the US government? Where do you see evidence of their presence, past or present, in your community today?

Investigate one of these peoples more deeply using a cultural iceberg model. Go beyond what is “visible” on the surface, such as food, celebrations, and dress, to uncover deeper, “invisible” aspects of culture, including values, social norms, ethics, and attitudes.

Begin by listening to indigenous classmates, teachers, or other living members of the community. They may not live in the area anymore, but many American Indian communities have a robust digital presence.

How might you honor, recognize, or make visible the story and culture of these people to others in your school or community? Share the model of a land acknowledgment with your students to spark their thinking.

Activity: American Exceptionalism

American exceptionalism is the belief or perception that the United States is special in comparison to other countries. While the concept has a long, complex history, exceptionalism took hold in the 19th century in a distinct way. The country’s rapid and frequently violent acquisition of territory was defended by many in power who claimed the United States was destined by God to expand westward. The link between manifest destiny and exceptionalism was further solidified in 1893 by historian Frederick Turner, whose “Frontier Thesis” claimed that the experience of pioneers who blazed the frontier uniquely strengthened and distinguished American democracy.

Many of the works in this module connect in some way to the concept of American exceptionalism. Which work of art in this module best illustrates this ideology? Ask your students to select one work, conduct additional research, and defend their choice using any visible and uncovered evidence.

Extend this activity by having a group discussion about American exceptionalism. What do your students think about this concept? How has American exceptionalism been both a positive and negative force? Where can they see this belief being promoted today?

Additional Resources

1816 map of the United States created by John Melish, Library of Congress

American Indian Removal: What Does It Mean to Remove a People? lesson unit, National Museum of the American Indian

Essential Understandings about American Indians, National Museum of the American Indian

Westward Expansion: Encounters at a Cultural Crossroads lesson unit, Library of Congress

Westward Expansion (1801–1861) lesson unit, Smithsonian American Art Museum

The Growing Crisis of Sectionalism in Antebellum America: A House Dividing lesson unit, National Endowment for the Humanities

Rae Carson, Walk on Earth a Stranger (Gold Seer Trilogy, Book 1) (New York: HarperCollins, 2016) – grades 7–12 historical fiction

You may also like

Educational Resource: People and the Environment

The US national park system exists in part because of artists.

Educational Resource: Expressing the Individual

Studying artists and their works invites explorations of identity and the human condition. What drives artists to create? What choices do artists make, and why? Sometimes artists directly engage with questions of identity in their artwork: Who am I? How do I relate to others, and how do they relate to me?