Language

On this Page:

Overview

Why and how do people protest?

How might works of art show support or advocate for a cause?

How are people, communities, and events affected by works of art?

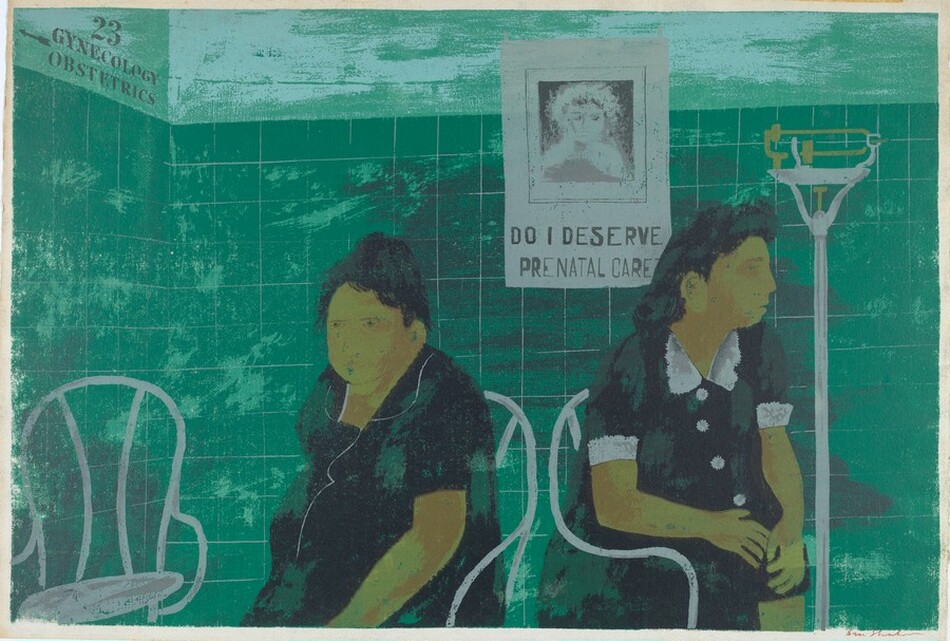

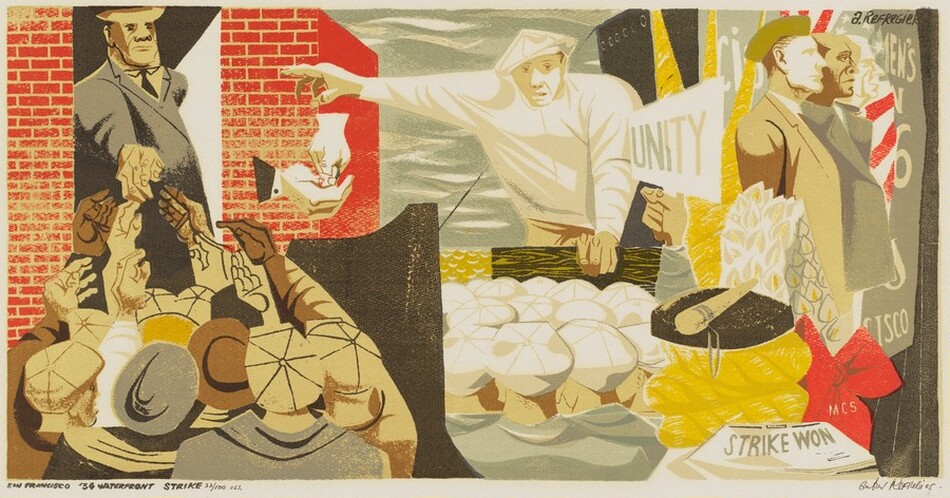

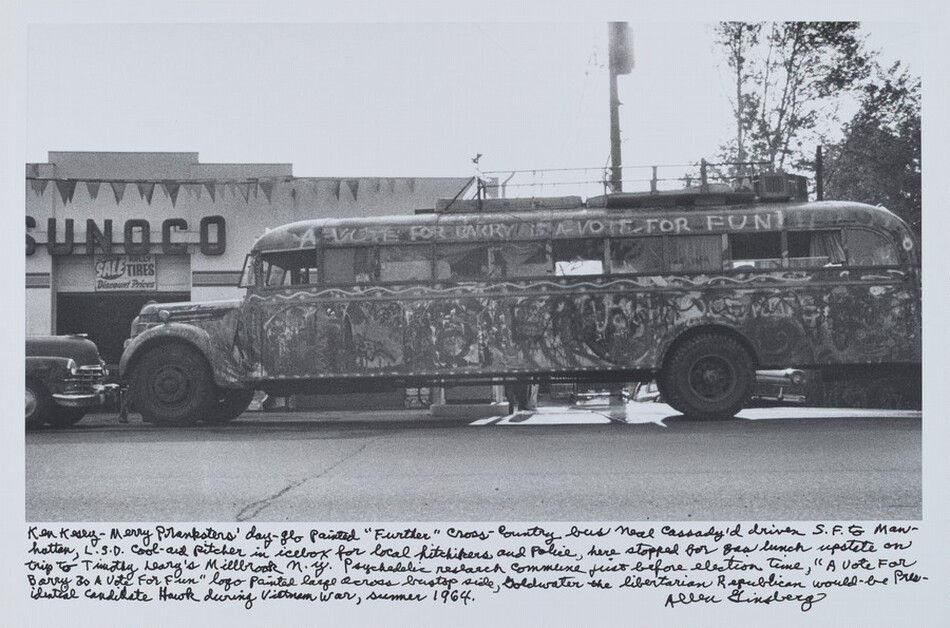

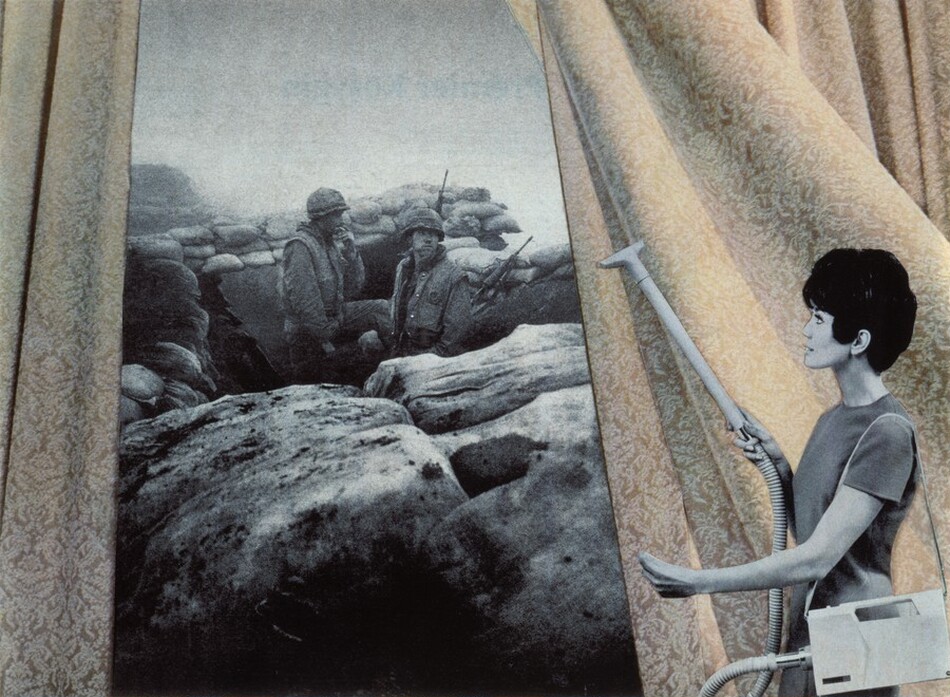

Artists in the United States are protected under the First Amendment, which guarantees freedoms of speech and press. This module features works created by artists with a range of perspectives and motivations. Some artists hoped to create widespread, systemic change, while others desired to make visible the vulnerable. Still others used their chosen medium to call attention to an issue, event, or system. Broadly, these artists hoped to improve conditions for themselves, others, or the world.

Paul Revere was one of these artists. His engraving depicting the Boston Massacre, published in 1770 in the Boston Gazette, is one of the most effective examples of war propaganda in US history. The image of British soldiers firing upon a crowd of Bostonians inflamed anti-British sentiments and bolstered residents who were increasingly frustrated by levies imposed by the Crown. Without the distribution of Revere’s engraving, the Boston Massacre may have remained an isolated incident instead of becoming a key event that helped trigger the Revolutionary War.

What made the Boston Massacre engraving so powerful?

To answer this question, consider these other questions:

- Who was Paul Revere? Why did he make this engraving and write the accompanying text?

- How might the image both represent or deviate from actual events?

- What artistic choices might Revere have made in order to promote his point of view?

- Who do you think Revere hoped to persuade and influence with his engraving?

- How do you imagine 18th-century viewers encountered and perceived the engraving?

- How might this work of art still influence or inform people today?

Revere’s engraving is widely recognized as an exaggerated depiction of actual events, but less widely known is that he did not conceive of the image. Artist Henry Pelham loaned his work in progress, titled The Fruits of Arbitrary Power, to Revere, who copied it and distributed his version before Pelham published his own. Why might this matter?

Every artist has a point of view. Today, artists make use of new platforms, tools, and means of communication to advocate for a cause or inspire action. What similarities do you see between the issues in the works of art in this module and contemporary issues today? How might you take action about an issue or cause? How do the works of art collected here provoke, reveal, move, or make change in some way?

Selected Works

Activity: Taking Creative Action

Like many artists and activists, Rupert García and Andy Warhol created posters to provoke audiences and show support for a particular cause. In this activity, students will think critically about protest, study poster design (especially the work of García and Warhol), identify an issue they care about, consider the pros and cons, and then create and publicly exhibit a poster.

How might art be a vehicle to express support for an issue or advocate for a cause?

- What does protest mean to you? Distribute large sheets of paper with the word protest circled in the middle to small groups of students. Ask students to work together to write down words or phrases that come to mind when they think about protest. Ask each group to share the results of their “protest map.”

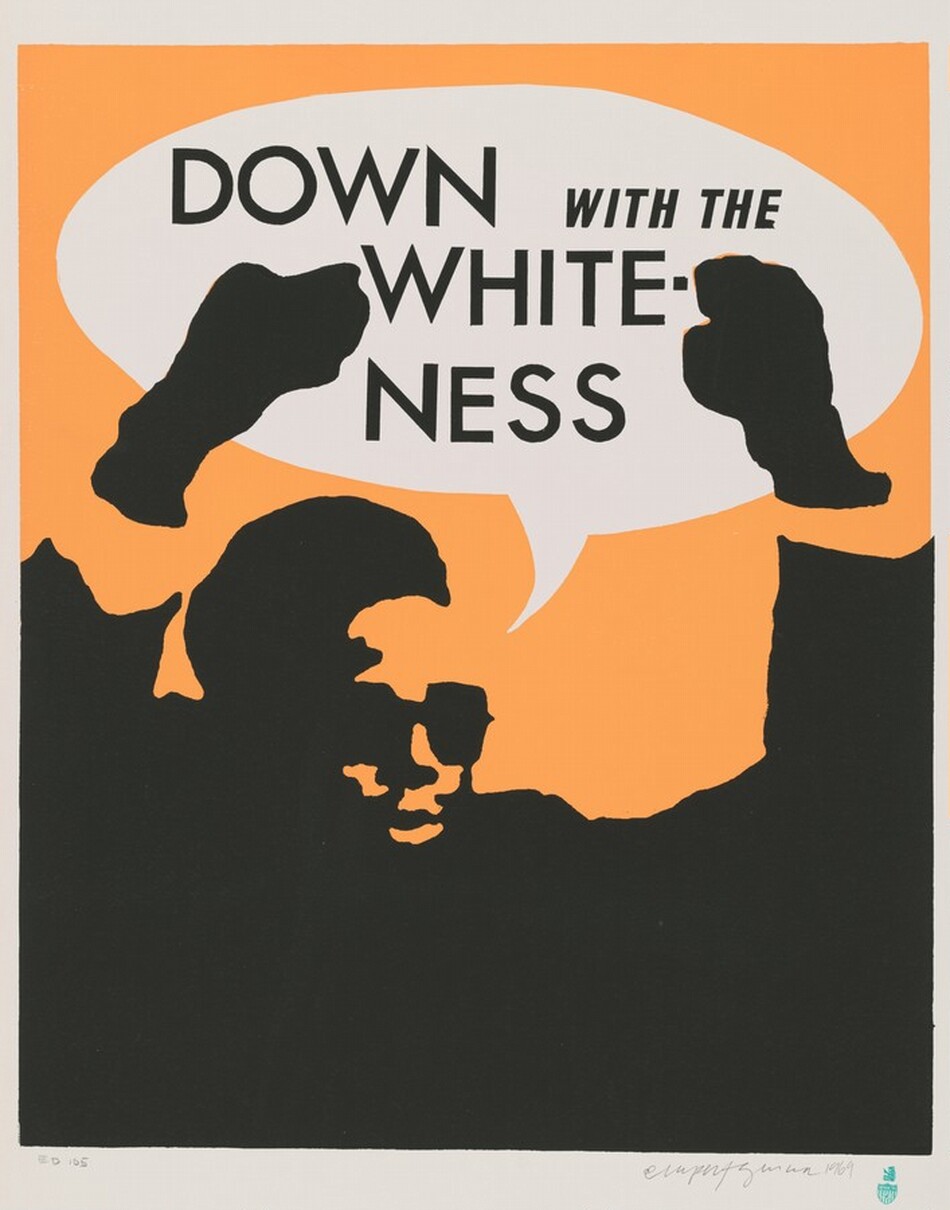

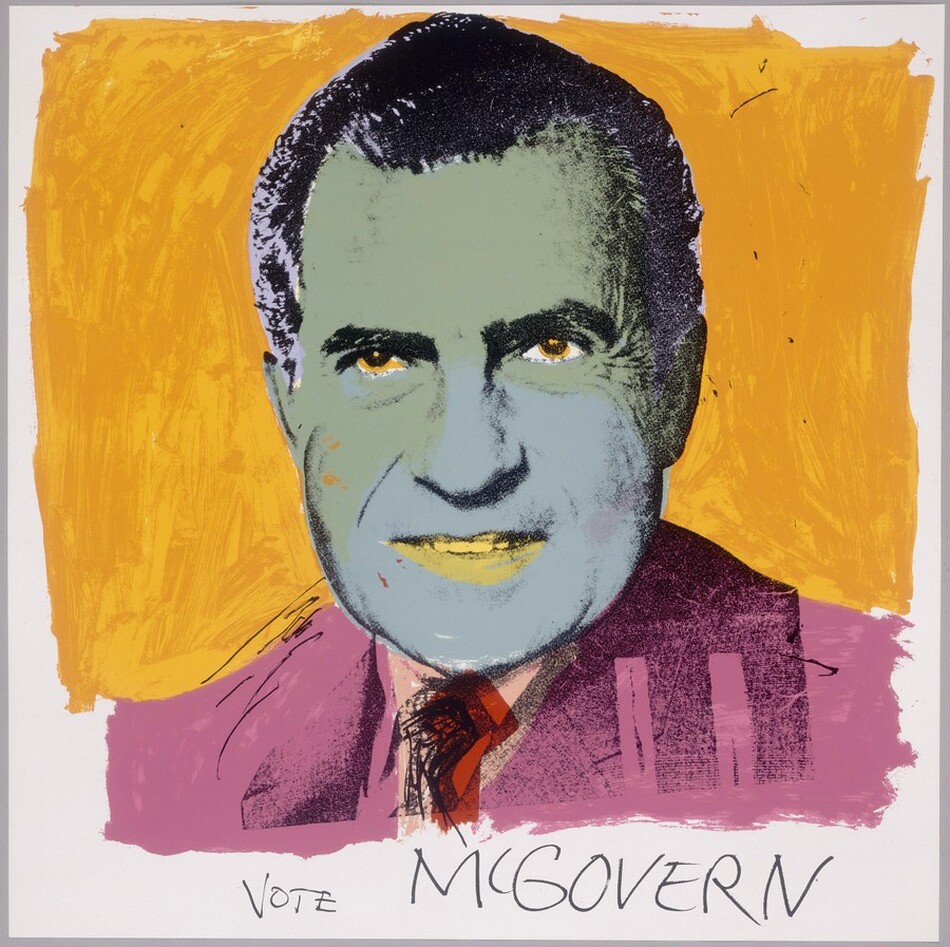

- Share digital or physical reproductions of García’s Down with the Whiteness and Andy Warhol’s Vote McGovern with small groups of students (only one work per group). Ask students to identify the parts of the image (its pieces and components; be specific), the purpose of the work of art (what it is for, why it might have been made), and what they wonder about the work (any questions they have). Then have groups with different images share their thoughts with each other. (Adapted from a Project Zero thinking routine.)

- Bring together the students and provide more information and context about how and why Rupert García and Andy Warhol created these works. Deepen the discussion by inviting students to conduct research about the Black Panther Party, the 1972 presidential election, and why García and Warhol took the positions they did. Discuss whether the students think these works of art were successful forms of protest.

- As a large group, generate a list of current events in the news. These issues might be of local, regional, or national significance, but they should be complex issues that the students care about. Examples might include universal health care, transgender rights, or immigration. Use a democratic method (e.g., sticker voter) to identify an issue that students care about most.

- Return students to small groups to identify opposing sides of the issue and generate a pros and cons list for each side using news articles and research. Students will then individually compose a position statement: where do they stand on the issue? They must use evidence from trusted news sources and studies to bolster their position, but they should also talk about why this issue matters to them, why it might matter to the people around them (e.g., family, friends, classmates, and neighbors), and why it might matter to the world. (Adapted from a Project Zero thinking routine.)

- Next, students will brainstorm memorable phrases, sayings, symbols, and imagery related to their issue that can be simply and clearly represented in a poster. How will they distill their position into a visual statement? Who will the audience for their poster be, and how will the poster be persuasive and memorable? Avoid clichés, such as smiley faces and peace signs. Incorporate time for feedback and improvement.

- Create posters using whatever mediums you have at hand, and then as a class determine how and when you would like to share them publicly. Could they be exhibited in your school, or is there an opportunity to use them in a public space outside your school to advocate for your cause? How might you use your posters to spark discussion or dialogue with others?

- Reflect: How successful was your public display of your posters? Do you think marches and protests make a difference? What would you do differently next time?

Additional Resources

Created Equal: The Abolitionists, Slavery By Another Name, Freedom Riders, Freedom Summer, and The Loving Story films and lesson unit, National Endowment for the Humanities

Boycotting Baubles of Britain lesson unit, National Endowment for the Humanities

Competing Voices of the Civil Rights Movement lesson unit, National Endowment for the Humanities

You may also like

Educational Resource: Immigration and Displacement

The United States is frequently described as a “nation of immigrants.” Immigrants have played a pivotal role in the country’s history and understanding of itself.

Educational Resource: Expressing the Individual

Studying artists and their works invites explorations of identity and the human condition. What drives artists to create? What choices do artists make, and why? Sometimes artists directly engage with questions of identity in their artwork: Who am I? How do I relate to others, and how do they relate to me?

Educational Resource: Faces of America: Portraits

The basic fascination with capturing and studying images of ourselves and of others—for what they say about us, as individuals and as a people—is what makes portraiture so compelling.