Our Communications Office coordinates press and community outreach for the museum’s collection, exhibitions, programs, research, campus, and other initiatives.

Access our press kit.

Journalists and other media representatives: sign up to receive the latest News Briefs.

General inquiries should be sent to [email protected].

Exhibition : American Landscapes in Watercolor from the Corcoran Collection

August 2, 2025–February 1, 2026

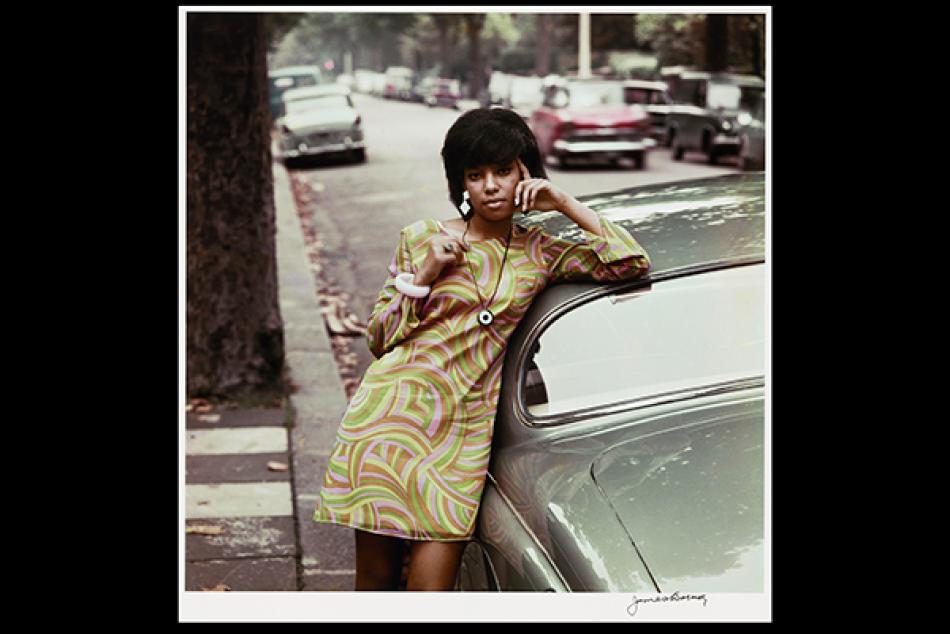

Exhibition : Photography and the Black Arts Movement, 1955–1985

September 21, 2025–January 11, 2026

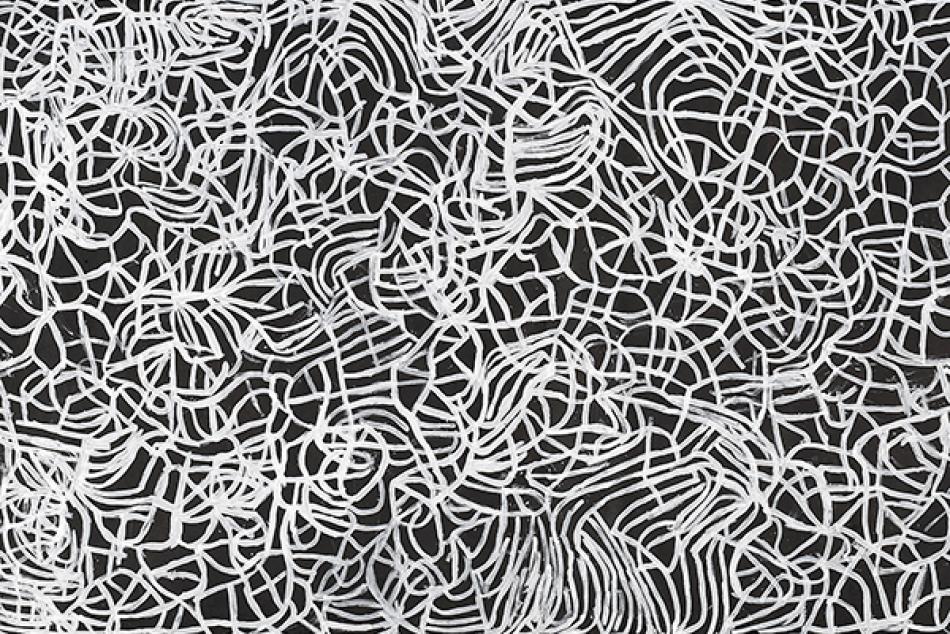

Upcoming Exhibition : The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art

October 18, 2025–March 1, 2026