The Key Set: 1884–1901

Publication History

Published online

Alfred Stieglitz, Sun Rays—Paula, Berlin, 1889, printed 1916, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.57

Key Set number 60

Alfred Stieglitz, Sun Rays—Paula, Berlin, 1889, printed 1916, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.57

Key Set number 60

Like any enthusiastic beginner, Stieglitz photographed avidly when he was a student in Berlin in the 1880s, yet much of his work from this time is known only through reproductions or as titles in exhibition checklists and reviews. The Key Set includes sixty-one vintage photographs from 1886 through 1890, but only six are exhibition prints; the rest are bound into six albums. Although the albums contain an eclectic mix, two photographs in particular illustrate the dominant issues in his work from this period. The first, Relief of Queen Louise, Berlin, 1886, is a study of the base of a statue, an exercise in recording contrasts of light and shade, and texture and pattern (Key Set number 30). The second, The Truant, Mittenwald, 1886, is a posed, anecdotal work, showing a young boy standing next to his disapproving mother (Key Set number 17). The first documents a specific object and place with a personal meaning for the photographer, unknown to the casual viewer (the sculptor was a friend). The second strives to be a picture with more universal appeal, depicting the same subject matter, sentiment, and concerns of popular painting. From the mid-1880s through the early 1900s, Stieglitz wrestled with the concept of photography as document and photography as art, struggling to reconcile what he perceived to be a fundamental dichotomy within the medium. Skeptical of the thing photography did so easily—record the world—he also questioned what it could to do—or should do—to be art, and whether its descriptive power precluded its ability to have greater artistic meaning.

In later years when he no longer felt compelled to validate photography by comparing it to anything else, Stieglitz tried to discount any influences on his early work, suggesting that photography and life, not painting or any other art, were his inspiration. In 1922 he claimed that he “knew nothing about painting” before 1905, and in 1935 told E. M. Benson that from his earliest years when he went into most museums, they “‘smelt like old leather’” and he longed to escape “‘into the street.’” Stieglitz was clear, Benson continued, “if a photograph reminded you of a painting, then it was neither one nor the other. . . . It was easy for him to believe this. Since he knew very little about plastic traditions, his vision was formed not by seeing art, but by seeing life.”

To a certain extent photography was, as Stieglitz said, his muse. When he began to photograph, probably in 1884, the medium captivated and challenged him as nothing else had done before. His teacher, Hermann Wilhelm Vogel, a highly respected photographer, scientist, and professor at the Königliche Technische Hochschule in Berlin, instilled in him a profound appreciation for the science and practice of the process. While Vogel exposed his students to the latest developments in the rapidly changing medium, he also grounded them in the basics of the process, assigning such problems as photographing a light object against a dark background to see if detail could be captured in both the highlights and shadows or instructing them to explore different subjects, such as landscape, portraiture, and even the reproduction of works of art to understand how each required “special study.” But Vogel also encouraged his students to think about photography’s aesthetics, its relation to the other arts, and especially the idea of what made “a true picture.” Truth, Vogel believed, was a matter of suppressing “the accessories” and revealing “the characteristic.” If photography only gave a “faithful picture of the form,” it would cede to the other arts the capacity to give “a more faithful picture of the character.”

Stieglitz deeply admired Vogel and rapidly assimilated his teachings. As Vogel directed, he tackled a wide variety of subjects—landscapes, genre studies, portraits, including one of Vogel himself—and he also photographed works of art (see, for example, Key Set numbers 1, 27, 32, and 33). He also experimented extensively with newly released products and he exhaustively explored the relationship of light to photography, studying how to use sunlight and shadow in nature, architecture, and interior views (see Key Set numbers 185, 35, and 60). Examples of all these technical experiments, among his most accomplished early works, are represented in the Key Set where three exist as vintage exhibition prints.

Yet, despite his assertions to Benson in 1935, Stieglitz, was, even as a child, deeply immersed in the “plastic traditions.” His father, Edward Stieglitz, a successful businessman and amateur painter, collected art and artists, and the young Alfred was very much a part of his father’s world (see Key Set number 237). In 1876 he listed Fedor Encke, a German portrait and genre painter who lived with the Stieglitz family for a year, as his favorite artist, and in the spring of 1882 he visited Wilhelm Gustav Friedrich Hasemann, another genre painter whom his father supported, at his home in Gutach, Germany. In the fall of 1882 when Stieglitz began his studies at the Technische Hochschule, he boarded with Fedor Encke’s older brother Erdmann, a neo-classical sculptor, teacher at the Berlin Akademie, and portrait photographer, who, as Stieglitz recalled a few years later, sent him “every day to look at the statues and the old Madonnas, and gradually things began to happen to me.”8 By 1884 Stieglitz’s more mature list of favorite painters included “Rubens, Van Dyke, and Angelo [sic].” He also became familiar with contemporary European artists. Through Hasemann he learned of such German and Dutch artists as Jozef Israëls, Max Liebermann, and Fritz von Uhde, while his friend Frank Simon (Sime) Herrmann, a New York painter studying at the Royal Academy in Munich in the 1880s, introduced him to the popular artists Franz von Defregger, Eduard von Grützner, Franz von Lenbach, and Ludwig Passini.

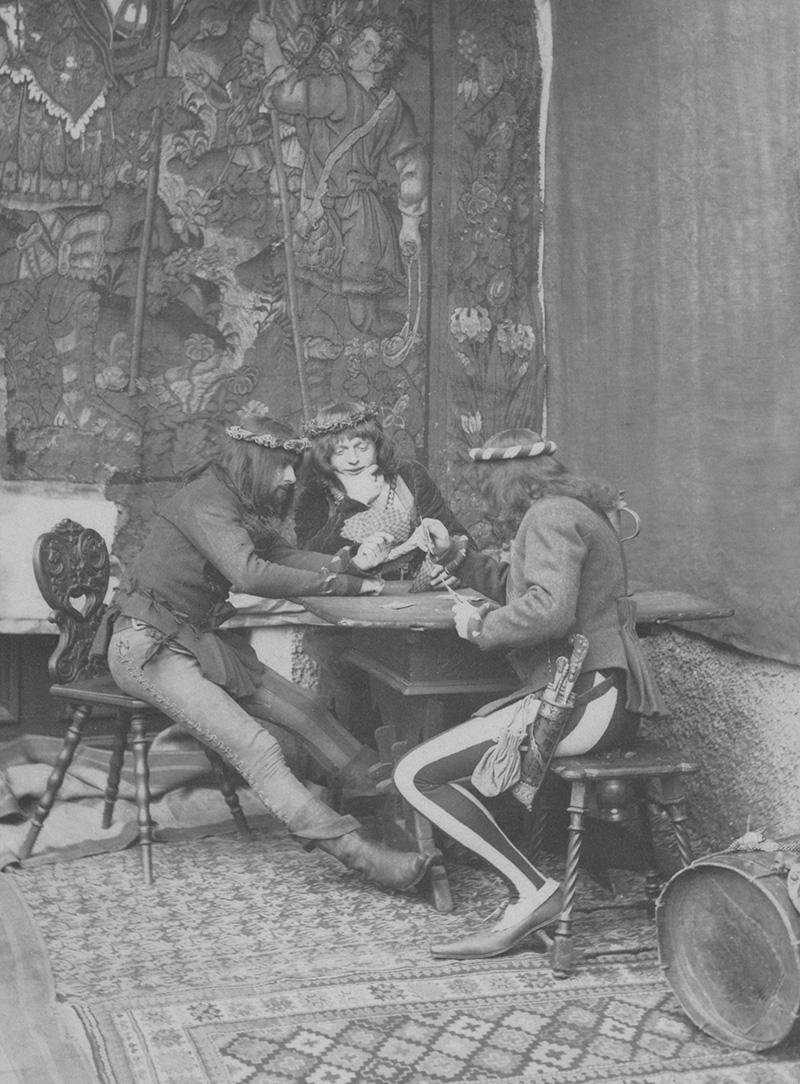

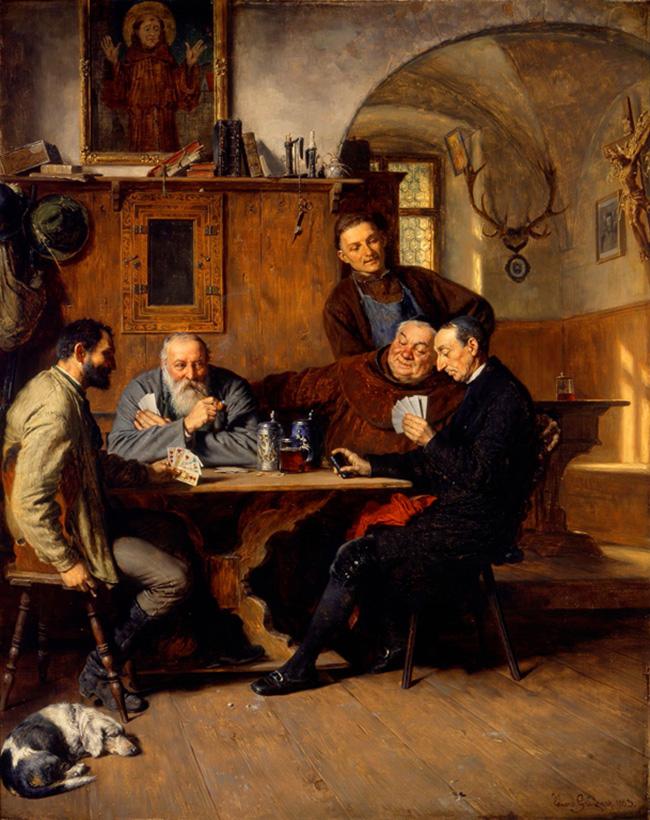

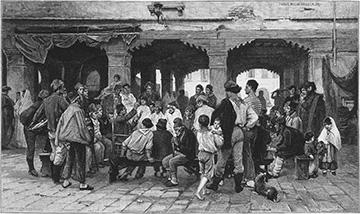

Displaying the worldly air of a young student, Stieglitz frequently referred to the work of all these artists in his writings of the time, and, when he began to photograph, he quickly found that he could easily replicate their anecdotal, narrative, and picturesque subject matter. As he himself later admitted, the Munich school strongly influenced his approach and Herrmann was especially instructive. When Stieglitz visited the painter in 1886 in Munich, Herrmann helped him stage a photograph, The Card Players, after Grützner’s hackneyed study of the same subject (figs. 1 and 2). When the two traveled together in Italy in the summer of 1887, Stieglitz, as he acknowledged at the time, accepted with alacrity his friend’s suggestion to make a photograph, A Favorite Occupation, Venice, in the manner of Passini’s Curiosity, which had recently been exhibited in Berlin to great acclaim. Stieglitz’s photograph The Last Joke, 1887, made on the same trip, may have its roots in Passini’s widely reproduced A Tasso Reader, 1871, which also revolves around the gestures of a single figure. (figs. 3 and 4). And even his admittedly far more complex Sun Rays—Paula, Berlin, 1889, may have had its inception, at least partially, in Hasemann’s A Picture of a Sweetheart, exhibited the year before in the Munich Anniversary Exhibition. In such photographs as The Truant, The Card Players, Meditation, or Peace—works that are hardly known today, but which won Stieglitz acclaim in the late 1880s and early 1890s—he imitated not only the titles and subject matter but also the manner of academic European painting. Yet, except for those bound into albums, few were spared Stieglitz’s subsequent editing.

While the subject matter for many of Stieglitz’s photographs made between 1886 and 1890 derived from contemporary painting, in important ways they were fundamentally different. His photographs were frequently more direct, literal, rooted to a particular time and place, and as the photographer Peter Henry Emerson noted when he awarded The Last Joke first prize in an 1887 competition, they were “spontaneous,” not contrived. When Stieglitz photographed people and allowed them to maintain eye contact with him, he was unable to achieve the idealized generalizations of contemporary painters. For example, the forthright appearance and confident pose of Leone, Bellagio, 1887, show an almost cocky individual, not a romantic Italian youth or street urchin (Key Set number 37). Recognizing these very difficulties and that this photograph, in particular, did not conform to prevailing pictorial expectations, Stieglitz made another portrait of Leone, not preserved in the Key Set, with his shirt unbuttoned and untucked, and his shoes and socks removed. Yet still his impishness was not suppressed. Admitting that the boy’s very individuality was his true subject, Stieglitz did not give this photograph an anecdotal title, such as The Truant, but identified him simply as Leone from Bellagio. This may have been one of his first realizations that while he could copy the subject matter and titles of other artists, mimic their sentiment, and even achieve some degree of fame by imitating them, he had yet to resolve the fundamental differences that existed between photography and the other arts: between the issues of form versus character, fact versus idea, specificity versus universality.

When Stieglitz returned to the United States in the fall of 1890, he immersed himself in the things that had nurtured him in Germany: his own photography, the chemical and technical experiments that so intrigued him, and the work of other artists. He joined the Society of Amateur Photographers of New York, and, most likely because lantern slide presentations were such an integral part of American camera clubs, began to explore this process in 1891. Encouraged by a fellow club member, William B. Post, he began to photograph with a small hand-held camera in 1892. His hand camera photographs from the early 1890s, especially those that he made into lantern slides and did not later carefully edit, reveal the stylistic and theoretical issues that continued to confront him at this time. Many are simply personal records, documenting The House in which Lou Schubart’s Mother was Born or banal family incidents, such as Listening to the Crickets, in which a dog peers into a bucket. But others, especially those of New York City, are more intriguing. Not carefully framed or composed, they have the random crops, odd juxtapositions, disjointed appearance, and immediacy so similar to countless other snapshots from the time, and depict the fragmentary, often transitional quality of urban life (fig. 5). Some appear to have been made with no particular subject in mind, as if in the hope that the act of photographing a scene would clarify its subject. Still more have an overall, non-hierarchical quality and give equal emphasis to all objects in the composition. In An Hour after the Snowstorm, for example, nothing, except perhaps the overall blanket of snow, is singled out for special attention (fig. 6). Yet Stieglitz made few prints of these photographs, preserved almost no vintage examples, and rarely exhibited them at the time, except as lantern slides. Although the hand camera would revolutionize photography, he approached it warily. Agreeing with the old adage that “to surrender one’s self to the imitation of nature would be to surrender all freedom, all individuality, and all ideals,” Stieglitz believed that “nature,” like the hand camera, “deals with the accidental; art with what is permanent.”

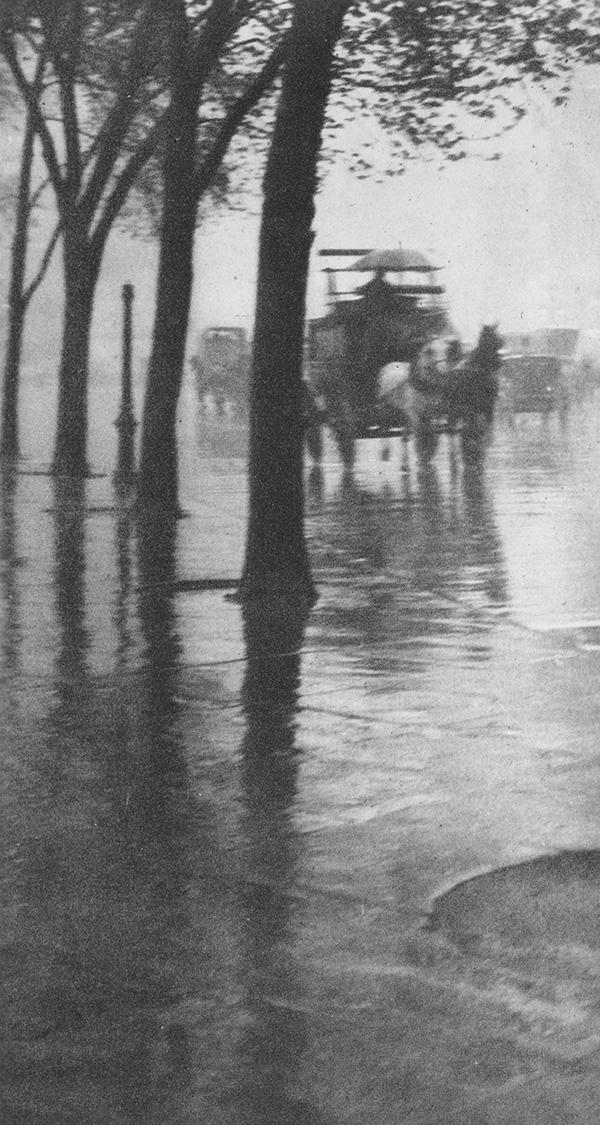

Winter, Fifth Avenue, 1893—the earliest vintage exhibition print from Stieglitz’s New York years in the Key Set—was also his first hand camera photograph to make the leap from nature, or document, to art, but only after it had been extensively reconstructed (Key Set numbers 82–87). Eliminating the pedestrians on the left and right, Stieglitz changed the composition from horizontal to vertical to focus attention on the horse-drawn carriage. To add scale and atmosphere, he enlarged the negative to 14 5/8 × 10 5/8 inches, making carbon prints on heavily textured watercolor paper that further softened the focus and increased the almost palpable sense of a blinding blizzard. Later in the decade he again reinterpreted the photograph, making it even more of a tonal poem by minimizing its contrast and eliminating the distracting railroad ties in the lower left (Key Set number 84). Far removed from its origins as a snapshot, Winter, Fifth Avenue was transformed into a work of art. Affirming its status as art, Stieglitz exhibited it more than a dozen times before 1900.

The transformation of Winter, Fifth Avenue reflects the influence of the American expatriate Peter Henry Emerson. In his highly controversial book Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art, 1889, Emerson insisted that camera vision was different from human vision, which selectively focuses on only one object at a time, according to its inherent interest, color, or prominence. Urging photographers to transcend their machines and their sharply detailed mechanical transcriptions of nature to render instead an impression of nature, Emerson ridiculed the idea of compositional rules. “Selection,” he maintained, “is one of the most—if not the most—vital matters in the art of photography.” One of Emerson’s most vocal champions in America, Stieglitz concurred that the camera was only a tool to be utilized in any way the photographer deemed appropriate, and he particularly stressed the importance of “atmosphere” and “tone” in photographic pictures. “Atmosphere is the medium through which we see all things,” Stieglitz explained, it “softens all lines; it graduates the transition from light to shade; it is essential to the reproduction of the sense of distance. . . . Now, what atmosphere is to Nature, tone is to a picture.” It was nothing less than “the dividing line between a photograph and a picture.”

Figure 7

William B. Post, The Critic, 1894, platinum print, Princeton University Art Museum, Museum purchase, bequest of Blanche Adelaide Hungerford Latimer Icaza in memory of her parents, Walter Rowland Latimer and Blanche Rodney Crowther Hungerford, 1995-121

Emerson gave Stieglitz license to move beyond the literalness and undigested inclusiveness of the snapshot and encouraged him to look at other painters. He frequently praised the art of Theodore Rousseau, Jean Baptiste Camille Corot, Jean-Francois Millet, Jules Breton, and especially Jules Bastien-Lepage, whose paintings composed of areas of suggestively broken brushstrokes and passages of almost photographic detail illustrated the photographer’s own theories of visual perception. Stieglitz approvingly cited both Millet and Bastien-Lepage’s work in his published writings in 1893 and purchased a copy print of the latter’s October Season: The Potato Harvest, 1879. At the same time, he also renewed his friendship with Herrmann, who interrupted his studies at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris and returned to New York in the fall of 1893 for several months. As is evident in Stieglitz’s portrait of Herrmann in his studio and Post’s study of both men, the two worked together, shared ideas and subject matter, and critiqued each other’s work (Key Set numbers 110 and 111, and fig. 7).

Figure 8

Max Liebermann, Die Netzflickerinnen (The Net Mender), 1887/1889, oil on canvas, Hamburger Kunsthalle. bpk Bildagentur / Hamburger Kunsthalle / Elke Walford / Art Resource, NY

In 1894 when Stieglitz traveled to Europe, he was a significantly different—more certain and directed—photographer than he had been when he left four years earlier. Like so many painters of the time—Gauguin most famously—Stieglitz on this trip searched for authenticity in cultures less technologically developed than his own: “I dislike the superficial and artificial,” he said in 1896, “and I find less of it among the lower classes.” Such sentiments no doubt explain the growing American fascination for all things Dutch and the great attention paid at the 1893 Columbian Exposition to both the Hague School and to the American artists who worked in Holland in the 1880s and early 1890s. This, as well as his own admiration for the studies of Zandvoort made by the Scottish photographer J. Craig Annan in 1892, led Stieglitz and Herrmann to travel to Katwijk aan Zee in the Netherlands. There they imbibed the influence of the Dutch artists Israëls and B. J. Bloomers, the Germans Liebermann and von Uhde, as well as the many Americans who worked in the area (fig. 8 and Key Set numbers 225–233). Avoiding the specificity of some of his earlier European photographs, Stieglitz presented the Katwijk people not as individuals, but as types, showing, for example the picturesque caps and aprons of the women, but not their faces. By placing his subjects in the middle ground, using a low vantage point, and often photographing groups of people, he emphasized their monumentality and community and by implication, the nobility of their labor and the stoicism of their nature. When photographing solitary figures, such as The Net Mender, he strove to summarize in one image “the life of a young Dutch woman,” as he wrote at the time, “toiling with that seriousness and peacefulness which is so characteristic of these sturdy people. All her hopes are concentrated in this occupation—it is her life” (Key Set number 212).

Figure 9

Wilhelm Hasemann, Wafferhäusle, from Wilhelm Jensen, Der Schwarzwald (Berlin, 1890), 87

Stieglitz visited his friend Hasemann in Gutach where he worked alongside the painter in his studio, photographing the same subjects, perhaps even the same people. (Compare, for example, Stieglitz’s Sunlight Effect to Hasemann’s own depiction of the subject, Key Set numbers 185–187 and fig. 9). While the portraits Stieglitz made in Gutach are often more specific than those from Katwijk—frequently revealing facial expressions, even at times a sense of genuine interaction with the photographer—they too are more generic studies of types, such as The Village Philosopher, and are infused with a sense of nostalgia for what had been lost through late nineteenth-century modernization (Key Set numbers 202–205).

He also returned to Venice. Turning away from the melodrama of Passini, he sought the everyday aspects of the city: a tramp asleep at six in the morning on the Piazetta near the Piazza San Marco, a solitary woman crossing the Ponte della Paglia, or women drawing water from wells (Key Set numbers 144, 142, 158–159, and 162–164). Fascinated by both the picturesque qualities of the canals and their abstract patterning of light and form, he made several photographs that echo both Annan’s Reflections—Amsterdam, which he had praised shortly before he left for Europe, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s studies of the same subject (Key Set numbers 145–154). And, as if to improve on his earlier studies of Leone, Bellagio, he seems to have consciously sought out a true street urchin in A Venetian Gamin (Key Set numbers 166–169).

The photographs Stieglitz made on his 1894 European trip established him as one of the leading photographers of the time. Like other contemporary pictorial photographers—Heinrich Kühn or Robert Demachy, for example—he utilized every tool available to transform these photographs into impressive exhibition pieces that would be immediately understood as works of art. In order to minimize the imitative, non-hierarchical qualities of photography and emphasize instead its selectivity and ability to extract meaning, he, once again, cropped many compositions. When he first printed the Hour of Prayer late in 1894 or early 1895, for example, he changed its format from a horizontal to a vertical, eliminating the incongruously modern house or hotel to the left, to focus on the two women and the church in the background, creating an image of rustic piety (Key Set number 218). Later in 1895 or early 1896 he made further adjustments: by including more of the surroundings and placing the women in the middle ground, he diminished their relationship to the church to make a work, now titled Scurrying Home, that spoke of the sturdy industry of these fisher folk (Key Set number 219). As he had done with Winter, Fifth Avenue, he made enlarged internegatives that allowed him to retouch his negatives more easily, remove distracting elements such as the anchor-line in Gossip—Katwyk, and make prints as big as fifteen, even occasionally twenty-one inches wide (Key Set numbers 208, 212, and 225). From these enlarged internegatives, he made carbon, gum bichromate, and photogravure prints, processes that allowed him to use the materials and palettes of a painter: he frequently printed these photographs on chine collé or thick, textured watercolor sheets in charcoal gray and brown, and even red, green, blue, and yellow on occasion. To reinforce the seriousness of his intent (and gain greater wall space), he used wide wooden frames of a color “chosen for harmony with the tone of the picture.” And to emphasize their textural and painterly qualities, he also often framed his larger prints without mats.

For the next dozen years, Stieglitz repeatedly showed his 1894 photographs in exhibitions and illustrated them in periodicals in both this country and in Europe: between 1895 and 1907 he exhibited and reproduced Gossip—Katwjk at least thirteen times, while he exhibited The Net Mender nineteen times and reproduced it sixteen times. He was also highly attuned to the critical reception of his work. In 1895 after the director of the National Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels selected Scurrying Home as one of a few photographs purchased for a future National Collection of Pictorial Photographs, Stieglitz included it in almost every exhibition he entered for the next seven years, showing it twenty-one times before 1903. Also in 1895 when the English photographer George Davison, whom Stieglitz had hailed the year before as one of the “giants” of the field, praised the “decorative effect . . . judiciously secured by the composition and trimming” of one of his photographs of goats by the Seine—itself inspired by Henri Lerolles’ Au Bord de la Route—he subsequently changed its title to A Decorative Panel (Key Set number 118). And when a photograph received little or no attention in the press, such as The Fisherman’s Return, he dropped it from his repertory (Key Set number 227).

These photographs also formed the core of Stieglitz’s first one-person exhibition at the Camera Club of New York in 1899: more than one third of the works shown were made on his 1894 trip to Europe. Surprisingly, less than one third were made in the following three years. Although he continued to assert that in “proper hands . . . lens, camera, plate, developing-baths, printing processes” were simply “tools for the elaboration of their ideas,” not “tyrants to enslave and dwarf them,” increasingly he appeared more interested in the process than the ideas and he seemed to lose his sense of direction: although he photographed his daughter Kitty, he made few other new pieces. Many of the works exhibited in 1899 were highly painterly and manipulated: carbon prints on “etching papers,” red and black gum bichromate prints on “toned” and “rough Whatman” papers, and two-toned, glycerine-developed platinum prints; only seven of which—all more neutral, charcoal-toned carbon prints—remain in the Key Set. Most of the new photographs Stieglitz exhibited were merely vehicles for technical explorations: he included three prints of A Study, 1898—platinum, manipulated platinum, and gum bichromate—as well as two manipulated prints of A Vignette, 1898, none of which are in the Key Set. In several respects, though, this show set a pattern he would follow in almost all of his subsequent one-person exhibitions. First, it was dominated by one idea: while later shows focused on one subject—portraiture, or New York—it sought to reveal the plastic nature of photography through the display of numerous manipulated prints. Second, although it included his most accomplished work of the period, his 1899 exhibition also presented photographs, such as The Street Paver, 1893, that had never before been exhibited, as well as a few newer and less well-tested works, such as An Icy Night (Key Set numbers 77 and 257–259). Thirdly, suggesting the important role that exhibitions played in directing his art and shaping his collection, after the close of the show, Stieglitz soon shifted course, abandoning manipulated printing techniques and eventually eradicating the most egregious examples from his collection.

Instead, he returned to a subject that would sustain him, if sporadically, for the rest of his career: New York. With the exception of Winter, Fifth Avenue, Stieglitz had not considered New York picturesque enough to garner attention in major exhibitions: after all, it did not have the sanctified appeal of Paris, London, or Venice. (He tested The Terminal in the Royal Photographic Society exhibition in 1894, and when it received no attention, he did not show it again for many years [Key Set number 92].) Only when night photography became, as he admitted, “the novelty of the year” did he seriously and systematically begin to reconsider New York’s artistic possibilities. Spurred by the studies of William Fraser, a member of the Camera Club of New York, he made two photographs, The Glow of Night—New York and Reflections: Night—New York that he included in a portfolio of photogravures, Picturesque Bits of New York and Other Studies (Key Set numbers 251 and 252). While only four of the twelve photographs were studies of New York, they elicited significant attention. The critic Sadakichi Hartmann praised Winter, Fifth Avenue as “a realistic expression of an everyday occurrence of metropolitan life.” If Stieglitz discovered “the picturesqueness of New York City, as he intends to do,” Hartmann concluded, “he will gain himself a place in our art life which the future art historians cannot overlook.”

Stieglitz, as always, responded to this praise. Approaching the subject cautiously, he did not strive to construct a new vision for the new city blossoming around him, but instead made it conform to notions of the picturesque so that it became more familiar. “Metropolitan scenes,” although “homely in themselves,” could have “a permanent value,” he wrote in 1899, if “the poetic conception of the subject” was revealed. To extract those lyrical aspects he—like so many pictorial photographers from this time—looked to Whistler. Transforming the cityscape into a landscape, abstracting and negating its specificity, he photographed it late in the evening, so that, as in An Icy Night, it became a Whistlerian nocturne of trees, snow, and distant lights rendered in a palette of silver, gray, and black (Key Set number 257). Shortly after the turn of the century, Stieglitz confronted the city somewhat more directly and photographed it during the day. In works such as From My Window, New York, 1902, he continued to conceal its newness, mute its visual cacophony, and render its manmade forms more natural by photographing in the rain or snow, and with few people, trolleys, or carriages (Key Set number 282). In other photographs such as Spring Showers—The Street-Cleaner, 1900/1901, a study of a stooped worker who is as fragile and powerless as the steel-encased sapling next to him, he suggested the precarious balance that existed between people, nature, and the new urban environment (Key Set number 269). While Stieglitz tackled the most audaciously original skyscraper of the time, the triangularly shaped Flat-iron, he mitigated its obstreperous newness by having it rise from a grove of trees in Madison Square Park (Key Set number 287).

Figure 10

Childe Hassam, Late Afternoon, New York, Winter, 1900, oil on canvas, Brooklyn Museum, Dick S. Ramsay Fund, 62.68. Photo: Brooklyn Museum

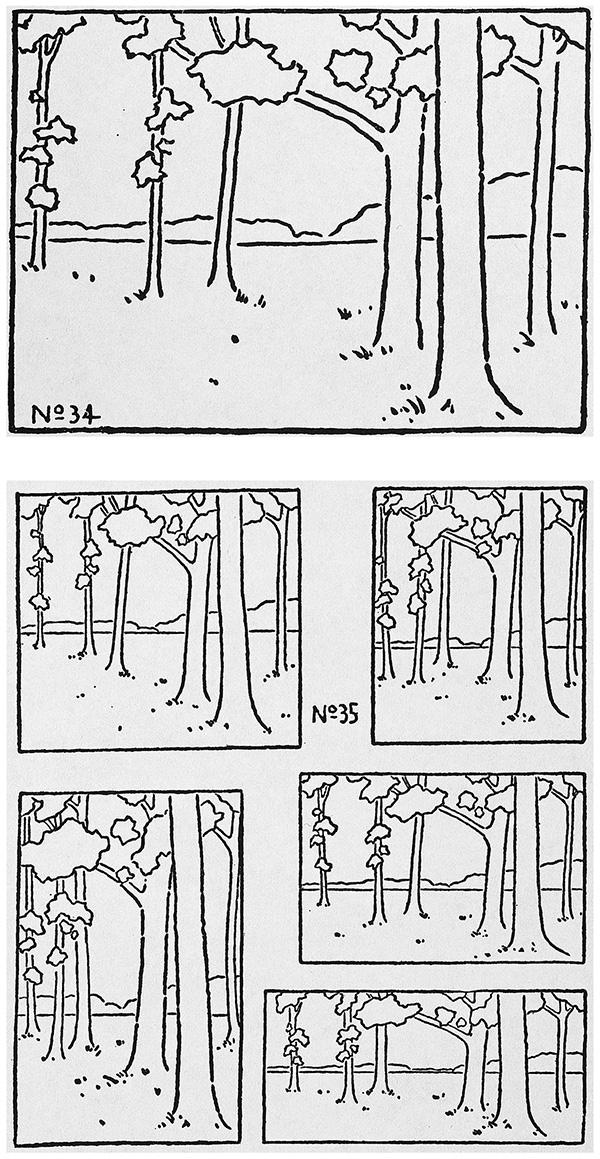

When Hartmann praised Stieglitz’s photographs of New York City in the late 1890s, the photographer told him that one of his favorite artists was the Norwegian Frits Thaulow. Widely admired and exhibited in the United States in the 1890s, Thaulow’s loose, atmospheric cityscapes, often depicting streets seen looking down from a second story window, have many parallels to Stieglitz’s own studies from this time. But, much closer to home, American artists, besides Whistler, also surely influenced his photographs of New York made from 1898 through 1904. Commercial photographers and popular illustrators had explored “Picturesque New York” for several years, publishing their studies in such journals as Scribner’s Magazine, The Century, and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, as had such painters as Childe Hassam (fig. 10). In addition, the tilted picture plane that Stieglitz employed in 1901, the elongated compositions, strong linear elements, and use of the silhouette and, occasionally, black borders, indicate that he, like other pictorial photographers, had thoroughly assimilated the lessons not only of Whistler and Japanese prints, but also the American educator and artist Arthur Wesley Dow, whose book Composition, 1899, included many exercises based on the idea of cropping to achieve the most effective use of line (figs. 11, 12, and 13).

Scribner’s Magazine published several of Stieglitz’s photographs of New York in 1903, along with an essay by John Corbin on “The Twentieth Century City.” Yet an odd disparity exists between his muted, and controlled photographs and Corbin’s eager, almost Futurist embrace of all that was new, untested, and potentially challenging about the new city. “Our life may be crude, grotesque,” Corbin wrote, “but is not this only because happily it has not yet become conventional. It is formless, no doubt, but for that very reason it may well be all the more alluring to an artist bent on divining new forms of beauty.” Despite his reticence, though, Stieglitz’s studies of New York from 1898 through 1903 are among his most accomplished early works because for the first time he grappled with an unequivocally modern subject, and the ideas and issues it raised. Recognizing their importance, Stieglitz unabashedly celebrated these photographs for the rest of his career.

Shortly after the turn of the century, Stieglitz thought of publishing two portfolios. In one, he wanted to reveal New York in “myriad, moods, lights, phases,” as a city “of transition—the Old gradually passing into the New.” In the second, he wanted to study the life of children, focusing on his daughter Kitty, but including others as well, “at different stages of their development.” As his “Photographic Journal of a Baby” indicates, it was intended to record its subject at all times of the day—Morning, Noon, and Good-Night—and in various activities—Going to the Beach or The Afternoon Visit. In its incompleteness, spontaneity, copious detail, lack of hierarchy, and seriality, as well as its suggestion that something of significance could result from an exceedingly common subject, Stieglitz’s “Journal” was as modern as his photographs of New York. Both admitted that the nature of their subject—New York City and a person—was so fluid and multifaceted that it could not be summarized in one photograph. Neither project, though, was fully realized and Stieglitz saved few of his photographs of Kitty (see Key Set numbers 263 and 264, 273–275).

Originally published 2002; minor adaptations have been made for the presentation of this text online.