American Paintings, 1900–1945: Into Bondage, 1936

Publication History

Published online

Entry

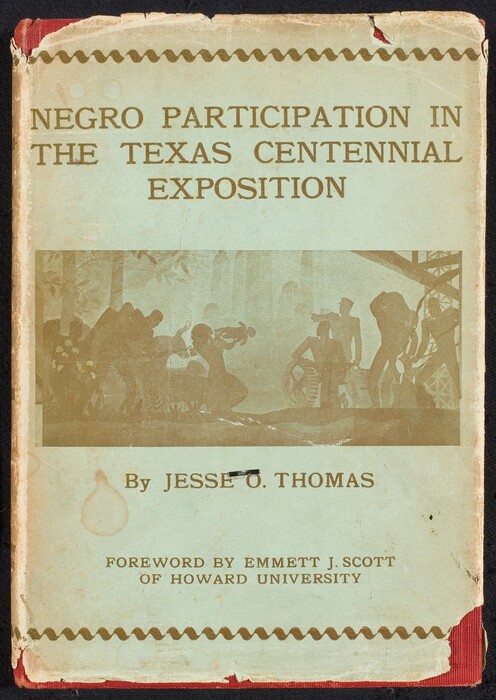

The modernist painter and graphic artist Aaron Douglas heeded the call of Harlem Renaissance intellectuals by acknowledging African cultural traditions as a source of pride and inspiration. He embraced a machine age aesthetic, but also integrated Egyptian and African motifs into cubist, precisionist, and art deco designs. Douglas’s illustrations for The New Negro, the 1925 anthology of Harlem Renaissance writers compiled by the philosopher Alain Locke, was his first major commission after moving to New York City from Kansas City in 1924. This project established his reputation as a leading artist of the new negro movement. In 1926, the writer Langston Hughes commended Douglas for inspiring younger African American artists to express their “individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame.” A decade later, when the Harmon Foundation was looking for an artist to paint a series of murals for the Texas Centennial Exposition in Dallas, Douglas was an obvious choice for the commission.

The four large canvases that Douglas made for the lobby of the centennial’s Hall of Negro Life welcomed more than 400,000 visitors . Only two of the paintings, however, have been located: Into Bondage and Aspiration . Along with The Negro’s Gift to America, a large horizontal work that hung between Into Bondage and Aspiration in the lobby of the exhibition hall , these canvases depicted the journey of African Americans from their native land to the 20th-century North American metropolis. Into Bondage illustrates the enslavement of Africans bound for the Americas. The Negro’s Gift to America featured an allegory of Labor as the holder of the key to a true understanding of Africans in the New World. Aspiration concluded the cycle by calling attention to the liberating promise of African American education and industry. A fourth canvas portrayed Estevanico, a Moroccan slave who accompanied the Spanish explorer Cabeza de Vaca on his expedition through Texas.

Like Douglas’s other murals of the same period, such as Aspects of Negro Life , created for the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library in 1934 (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture), the Texas centennial canvases were unified by a subdued palette, silhouetted figures, and repeated motifs that held personal meaning for the artist. In the Gallery’s painting, concentric circles Douglas frequently used to suggest sound—particularly African and African American songs—radiate from a point on the horizon where slave ships await their human cargo. Warm earth tones accent a palette of cooler blues and greens, just as the composition’s undeniable rhythm competes with an overall timelessness. Silhouetted figures move in a steady line to the distant boats, their rust-colored shackles creating a staccato rhythm echoed by the framing foliage. Patchy brushstrokes activate the surface, imbuing the painting with a texture and liveliness that belie the static precision of crisply delineated forms.

For the pose of the central male figure, whose head is turned in profile but whose square shoulders and torso face forward, Douglas looked to Egyptian art as a source of pan-African nationalism. Similarly, the slit-eye masks made by the Dan peoples of Liberia inspired the man’s narrow slash of an eye. Standing on a pedestal that foreshadows the auction block from which he will be sold, he is the only figure in the composition whose shoulders rise above the horizon. The man’s elevated form and uplifted head, cut across by a ray of starlight, signal eventual freedom for his race. A woman who raises her face and shackled hands to the same star, her fingers grazing the horizon, also foretells a distant future without slavery. According to Douglas, the star and ray of light, which appear in a number of his paintings, represent the North Star and the divine light of inspiration. Douglas, a member of the Communist Party USA, may also have included this motif as a political symbol and to advocate socialism as a means of achieving equality for African Americans.

Regardless of its specific meaning, the star’s message of hope is clear. Renée Ater has shown how the Texas Centennial’s Hall of Negro Life offered African Americans the opportunity to “re-articulate their racial and national identities” and “reshape historical memory.” Similarly, Douglas’s murals, she writes, “set out to rethink and to develop alternative narratives of black history and contemporary life that were embedded in visual references to slavery.” By the 1920s, historical representation and cultural expression had become important signifiers of black progress in the public spaces of American fairs, serving as “a springboard from which to educate blacks about how their rich American and pan-African heritage would assist them in charting their future.” Douglas’s forward-looking, modernist aesthetic that paid tribute to an African past was thus a fitting visual complement to the fair building’s empowering themes.

On another level, the mere existence of the murals was indebted to ongoing African American struggle. When the Texas legislature originally neglected to allocate funds to allow African Americans to be included in the centennial, African American community leaders in Dallas took it upon themselves to apply for federal money to participate. Most Dallas press coverage was enthusiastic when the Hall of Negro Life opened in 1936 on June 19, or Juneteenth, an African American holiday commemorating the end of slavery. Consistently high attendance figures at the exhibition hall, however, did not succeed in dispelling deep-seated prejudices. Douglas’s paintings so impressed white fairgoers that they refused to believe that an African American artist had made them. To help persuade incredulous visitors, administrators posted a sign reading: “These murals were painted by Aaron Douglas, a Negro artist of New York City.”

For Douglas, the commemoration of slavery was critical to the rewriting of the history of Texas and to the acknowledgment of African American contributions to the progress of both state and nation. By doing so in a public mural, Douglas was able to reach hundreds of thousands of viewers and, at the same time, proclaim the centrality of African Americans within modern American visual traditions.

Technical Summary

The painting is executed on a plain-weave, lightweight fabric mounted on a modern replacement, expansion bolt stretcher with no crossbars. The oil type paint was applied over a pre-primed, smooth, opaque, cream-colored ground. Graphite underdrawing is readily visible through the thin paint layer. It appears that Douglas fully outlined the design before painting using a straight edge and some sort of compass or template for the geometric shapes. Other design elements seem to be drawn freehand. Underdrawing is most visible in areas where Douglas did not follow his outline exactly when he applied the paint. The infrared examination confirms the extent of Douglas’s underdrawing. The x-radiograph shows no significant artist changes, which is to be expected considering the meticulous planning evidenced by the underdrawing. Douglas used a thin fluid paint that was sometimes so liquid that small downward drips occurred. There is no modeling of forms. Instead, Douglas created interest within the flat shapes by varying his paint application. Sometimes it was thin and transparent, sometimes it was applied with active brushstrokes showing areas of the ground beneath, and sometimes it was applied with textured impasto. There are many inclusions, such as fibers, brush hairs, and lint in the paint.

Renee Ater states that the painting was made on-site at the Texas Centennial hall for which it was commissioned, and this is supported by physical evidence. Around the periphery of the painting there is a 7/8-inch-wide strip in which there are multiple nail holes and the design elements are a different color than in the rest of the painting. This probably indicates that the painting was executed on a fabric mounted directly to the wall, and then wooden strips were affixed over the edges to serve as a frame. The painting’s first known conservation treatment was executed by Quentin Rankin in 1987. According to his report, he received the painting stretched on a flimsy seven-member stretcher and the canvas had several tears in it. These tears were found in the proper left leg of the foreground male figure, just above the chain, above the inner tip of the lower palm frond at the lower right edge, on the bottom edge of the same palm frond and below it onto the blue background, at the lower left near the base of the wide frond that touches the foreground women’s head and goes through the plant with smaller foliage as well, and at the top left in the dark purple brown foliage in the second leaf from the top. When the painting arrived in Rankin’s studio it was also defaced with scratches, impact cracks, grime, and pencil graffiti. The conservator cleaned the grime layer from the painting, lined it onto an auxiliary support using Beva adhesive, and mounted the painting on its new stretcher at a slightly larger dimension. Finally, he filled and inpainted the tears and losses, including some of the graffiti, and varnished the painting with a synthetic resin, even though there was no indication that the artist had ever varnished the painting. In a recent treatment in 2016, Gallery conservator Jay Krueger removed this varnish and inpainting, applied new retouching, and left the painting unvarnished as had presumably been intended by Douglas. In both treatments it was impossible to remove the pencil graffiti.

Collection of Steven L. Jones

Collection of Steven L. Jones

The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

US National Archives

US National Archives

© The New York Public Library, The New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Art and Artifacts Division

© The New York Public Library, The New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Art and Artifacts Division