Building the Collection: Multiple Modernisms

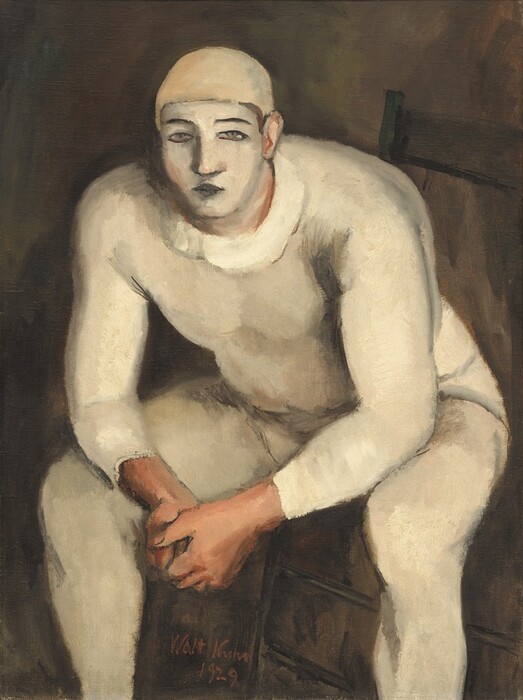

The idiosyncrasies of the Gallery’s American modernist collections, the works that cannot be easily categorized, or those created by less well-known figures or by artists whose styles constantly shifted, hint at something essential about the early modernist period in America in general: its inclusive, eclectic, radically democratic spirit and, concomitantly, its passionate belief and defense of independent artistic expression in all forms. Walt Kuhn, for example, was a key organizer of the landmark 1913 Armory Show and an adviser to John Quinn, one of the most adventurous American collectors of the early 20th century. But around 1930 Kuhn’s interest in the more radical forms of modernism waned, and he felt little sympathy for the alternative approaches being offered by the regionalists or the social realists. In 1968 and 1972, a group of seven paintings, four still lifes, and three figure paintings from this late period of Kuhn’s career were accessioned by the Gallery. They show an artist who, while well aware of the lessons of Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso, was searching for an indigenous, authentic style of painting akin at times to American folk art. Something of the loneliness and anguish of Kuhn’s plight in trying to establish an autonomous artistic identity is registered in The White Clown [fig. 1], a staged depiction of an actor in the role of a circus performer, a work exhibited at the newly opened Museum of Modern Art in 1929.

In a similar but stranger, more morbid, and more forlorn vein are Ivan Albright’s There Were No Flowers Tonight, a 1972 gift from Robert and Clarice Smith that was included in the Museum of Modern Art’s landmark 1943 exhibition American Realism and Magic Realism, and Rico Lebrun’s The Ragged One, a painting accessioned by the Gallery in 1974. Like Kuhn, Albright and Lebrun investigated the plight of figures existing at the edges of society in works that mirrored their own multifaceted personas. That complexity was evident in their far-flung interests and experiences. Albright, born in Chicago, was a medical illustrator for the army in World War I, fascinated by bodily decay and decline. Lebrun, from Naples, Italy, produced a series of harrowing works depicting the Crucifixion and the Holocaust. Both men also coincidentally worked in Hollywood in the early forties: Albright on the portrait featured in MGM’s horror/drama based on Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Grey (1944) and Lebrun as an animator on Walt Disney’s Bambi (1942). Another example of this type of untamed individualism is Lamar Dodd, a southern artist who taught and worked in his home state at the University of Georgia. Winter Valley (anonymous gift, 1971), a bleak view of the outskirts of Athens, Georgia, seems to mark Dodd as a quintessential regional painter. Yet in the 1960s Dodd went on to work for NASA, creating paintings of the Mercury and Apollo space programs, several of which were shown at the Gallery’s exhibition Eyewitness to Space in 1965, and later devoted some of his last canvases to events like the Oklahoma City bombing and the O. J. Simpson trial.

Even works by artists in the collection who more consistently pursued abstraction can complicate standard modernist narratives. In 1988, Raymond Jonson’s Variations on a Rhythm‑‑U (1933) was given to the Gallery by Dr. and Mrs. Robert Fishman. Jonson was born in Iowa and was influenced by the Chicago Armory Show in 1913 and Chicago modernists like B. J. O. Nordfeldt. In 1924 he moved to New Mexico, where he founded the Transcendental Painting Group in 1938. Jonson, in contrast with the artists of the Henri and Stieglitz groups, is representative of the many modernists who, because their careers unfolded outside of New York City, remained outside the dominant histories of modernism written by, and to some extent for, New Yorkers.

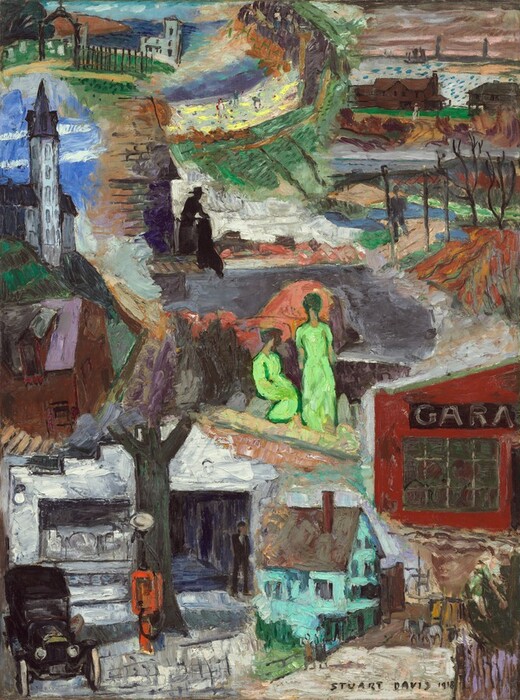

In 1991, two works by Milton Avery entered the Gallery’s collection during its 50th anniversary: Artist and Nude (1940) and Mountain and Meadow (1960). Although born in 1885 and part of the core generation of American modernists, Avery did not develop his essentially self-taught style until the early 1930s. With its broad fields of lyrical color and simple outlined forms that border on abstraction, his style hangs in the balance between the innovations of his peers like O’Keeffe and Dove and those of the postwar color field painters like Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb, whom Avery taught. By contrast, Stuart Davis at the age of 21 was one of the youngest participants in the 1913 Armory Show in New York. Multiple Views [fig. 2], the 1918 painting the Gallery received from his son Earl Davis in 2008, anticipates Davis’s precocious gift for integrating a variety of seemingly disparate ideas and influences, from cubism to urban realism to popular commercial imagery, into a cogent whole, a talent that he would continue to develop throughout his long and productive career. While Avery’s images seem to lyrically drift apart and float free from reality in broad amorphous shapes and clouds of ethereal, atmospheric color, Davis created sharp visual and thematic connections that bound disparate experiences together into a seemingly unbroken chain. This practice epitomized what Wanda Corn, borrowing Davis’s own formulation, has called American modernism’s “Amazing Continuity.”[1]

The idea of multiple modernisms has shaped the recent discourse about early 20th-century American art. Contemporary scholars have sought to restore the era’s complex fabric by questioning the dominant teleological narrative constructed by major critics and historians at midcentury. Those accounts often subordinated and obscured the accomplishments of the first American avant-garde in order to privilege the postwar innovations of the abstract expressionists and others. The current emphasis on multiple narratives and questioning of traditional historical groupings and boundaries can be placed under the rubric of “postmodernism.” Yet in many ways it simply mirrors the radically democratic aspirations of the first generation of American modernists. Henri and his followers were constantly searching for a framework that would allow artists of all types, from academicians to experimentalists, from the strict rule makers to the anarchistic rule breakers, to productively interact and coexist. Stieglitz’s activities at 291 challenged boundaries and restrictions of all kinds: the notion of a dominant European avant-garde, the preeminence of the marketplace, and an entrenched fine art establishment that elevated painting and sculpture while ignoring his chosen medium, photography. This eclectic vision found expression in both the influential smaller group shows of the era, such as Henri’s 1908 exhibition of The Eight and The Younger American Painters at Stieglitz’s 291 gallery in 1910, as well as in the mammoth, omnibus installations like the 1913 Armory Show and the Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in 1917. During the 20s and 30s, the ambitious task of presenting the many disparate, often contradictory, and always contentious strands of American modernism began to be taken up by museums.

Very early in the National Gallery of Art’s institutional history, through Phillips and Walker, something of the all-encompassing philosophies of Henri and Stieglitz found their way into the Gallery’s approach to American modernism. Phillips wrote eloquently of the “many mindedness” and “many sidedness” of modern painting: “Ours is a many-minded world. . . . Our concern should be to give those many minds a chance by not encouraging the molding of a mass-mind. . . . In our search for the best of every kind of painting an attitude of reflective, skeptical, critical, but always sympathetic and unprejudiced observation has an advantage over the attitude of a pledged person.”[2] Questioning what he called “orthodox modernism,” Phillips admired “that rare quality of the critical mind—the ability to perceive that in the house of art there are many mansions, and every single one of them at least interesting.”[3] In 1948, Walker echoed Phillips’s catholicity in an article discussing the Gallery’s fledgling American collections: “In the House of Art there are many mansions . . . we have tried to show every important phase of American painting.”[4]

Notes

[1] See Wanda Corn, The Great American Thing: Modern Art and National Identity, 1915–1935 (Berkeley, 1999).

[2] Duncan Phillips, “Modern Art and the Museum,” American Magazine of Art 23, no. 4 (October 1931): 275.

[3] Duncan Phillips, review of The Pathos of Distance by James Huneker, Yale Review 3 (April 1914): 594–596. Phillips was describing the art critic James Huneker.

[4] John Walker, “American Masters in the National Gallery,” National Geographic Magazine (September 1948): 324.