Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century: Girl with the Red Hat, c. 1669

Entry

Girl with the Red Hat has long puzzled scholars of Johannes Vermeer. Although widely loved, the work’s attribution has proved problematic. Its authorship is often discussed in conjunction with the only other panel painting in Vermeer’s oeuvre, Girl with a Flute , and many have wrongly viewed the two works as pendants. Girl with the Red Hat achieves a different effect from any other Vermeer work. The subject’s pose and expression, deep blue robe and fiery red hat, and face modeled with carefully selected green and rose tones give this work a unique vibrancy. Unlike most of Vermeer’s figures, she engages directly with the viewer, turning outward and gazing at us expectantly.

The motif of a girl looking over her shoulder at the viewer is common in Vermeer’s oeuvre, although in no other instance does she lean an arm on the back of a chair. The orientation of this chair has long puzzled scholars, who, under the assumption that it belongs to the seated woman, have complained that the left finial is much larger than the right and angled too far to the right. The finials, moreover, face toward the viewer. But if they belonged to the chair upon which the girl sits, they should face toward her, as in, for example, Frans Hals’s Portrait of a Young Man, where only the back of the lion’s head is visible.

The most convincing explanation is that the chair faces out of the picture space; its seat, out of view below the frame, extends into the viewer’s space. Thus, the repoussoir on which the woman leans is meant to be the back of the viewer’s chair—a crucial component of the artist’s strategy to capture our attention and draw us into the scene. Vermeer most frequently depicted an empty chair seen from the back, which distances the viewer from the scene. A chair turned toward the viewer appears in his earlier work A Maid Asleep , where the dozing woman and the empty chair beside her suggest a private moment between the maid and an absent visitor. In Girl with the Red Hat, Vermeer brings the viewer into that intimacy. While most of Vermeer’s women invite contemplation and distanced admiration, the figure in Girl with the Red Hat leans forward to speak to us, demanding our complete engagement.

Girl with the Red Hat is Vermeer’s only known work painted on panel and his first known foray into the schematic rendering of forms that characterizes his late style, in which he exaggerated contrasts of light and dark and used broad, brushy paint strokes. This abridged approach to the rendering of light effects is particularly noticeable in the contrast between light and shadow in the folds of the cloak, where he quickly applied pale, lead-tin yellow highlights with short strokes that he deliberately did not blend into the deep shadows of the fabric. He also abandoned the delicate modulations of tone and tiny circles of highlight that he used to evoke the patterns of light on fabric in works like A Lady Writing and Woman Holding a Balance. The brush Vermeer used throughout Girl with the Red Hat was far larger than would be expected for such a small painting, which allowed him to render forms such as the red hat with dashes of paint two or three times the size of the yellow highlights on the sleeve of the woman in A Lady Writing. Even the white reflections on the iconic lion-head finials are outsized—a characteristic that several scholars have suggested may be evidence of Vermeer’s use of a camera obscura.

Such artistic choices have no precedent in Vermeer’s oeuvre, but they do foreshadow works like The Lacemaker and Woman Writing a Letter, with Her Maid . In each of these works, Vermeer defined the face with sharp-edged patches of highlight that trace the bridge of the nose and curve around the inner corner of the eye, and he painted the costumes and fabrics by placing bright, angular highlights against deep shadows. In The Lacemaker, he conjured the colored threads cascading from the sewing cushion with remarkably fluid dribbles of paint, each accented with round highlights of the same color. This handling recalls the untamed wisps of vermilion paint that flicker along the edge of the beret in Girl with the Red Hat. The round highlights that harmonize with their settings are reminiscent of the dabs of pink in the red hat and the glistening spots of colored light on the girl’s lip and eye: pale pink at the darkened corner of the mouth and pale green for the eye in the greenish shadow. The similarities of these works argue for a close chronological relationship. It seems probable that Vermeer painted Girl with the Red Hat around 1669.

This dating reflects a shift in thinking about the place of Girl with the Red Hat in Vermeer’s oeuvre. In 1995 Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. argued for a slightly earlier date of 1666/1667 owing to the likeness he saw between the way Vermeer applied highlights in this painting and in the chandelier and tablecloth in The Art of Painting from around 1667 (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). “These similarities,” he wrote, “as well as the comparably generalized forms of the girls’ heads in the two paintings, argue for a close chronological relationship. It seems probable that both works were executed around 1666 to 1667, slightly before The Astronomer (Louvre, Paris), which is dated 1668.” This dating placed Girl with the Red Hat much closer in time to the highly refined and carefully blended brushwork of A Lady Writing and Woman Holding a Balance. However, the clear affinities between Girl with the Red Hat and his later works instead suggest that this painting should belong to a new phase of Vermeer’s career and is, perhaps, even its inaugural work. Wheelock’s guidepost of The Astronomer usefully emphasizes this point.

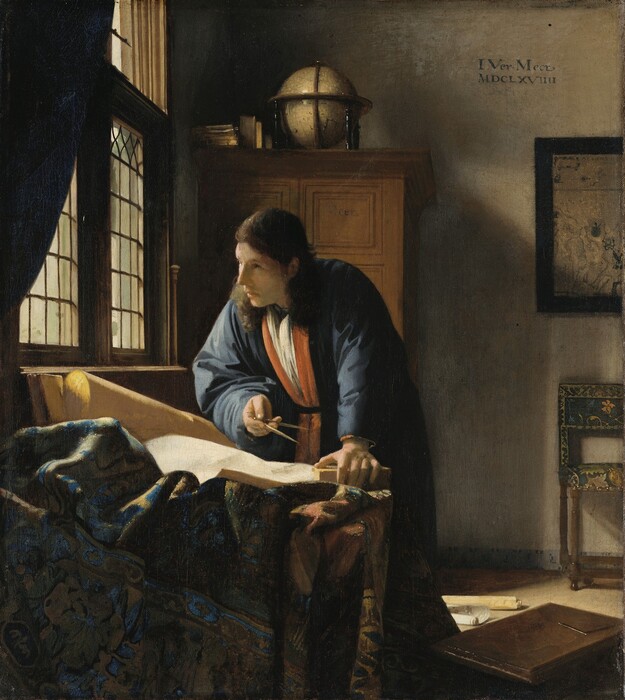

Vermeer rarely dated his paintings, but The Astronomer and its pendant, The Geographer , dated 1668 and 1669, respectively, offer intriguing material evidence of when this new abstraction entered Vermeer’s practice. Because of the compositional affinities between the paintings—the same model depicted in almost identically furnished rooms and the same “IVMeer” signature on the cabinets behind the figures—it seems likely that they were both initially painted in 1668. But Vermeer signed The Geographer a second time on the rear wall, indicating that he revisited the painting, and it was probably after those revisions that he added the date of 1669.

In The Geographer (but not in The Astronomer) Vermeer developed the fall of light by adding or reemphasizing certain highlights. Where he had first used a dark yellow highlight to suggest light transmitted through paper in the opening of the rolled map below the window, he later amplified this optical effect by building up a schematic patch of thicker and brighter yellow paint. He initially painted the faces of both subjects with similarly blended brushwork ranging from warm highlights to cool, gray-green shadows, but he later reemphasized the light from the nearby window in The Geographer by adding thickly brushed, bright pink paint on the illuminated side of the face, creating a hard-edged, planar highlight curving around the high forehead and tracing the bridge of the nose. This revised patch of light is reminiscent of the final, bright pink highlight on the cheek of Girl with the Red Hat. As in that painting, the highlight in The Geographer amplifies not only the contrast of light and dark but also the chromatic contrast between green and pink tones in the face. It seems most likely that Vermeer began to experiment with abstraction after he completed The Astronomer, first in Girl with the Red Hat and then in The Geographer. Indeed, the deceptively modest Girl with the Red Hat seems to have initiated the heightened abstraction and greater contrasts of both light and color that became hallmarks of Vermeer’s later style.

If Girl with the Red Hat served as an experiment for the brushwork and lighting that would come to characterize Vermeer’s late work, then we may also begin to understand his choice of an oak panel support for that work. There are no other paintings on panel in Vermeer’s extant oeuvre, which has prompted speculation about its use in this instance. It may simply have been that, for a small study, panel seemed a more appropriate support than canvas; but it may also be, as Wheelock has hypothesized, that the hard, smooth surface of a wood panel gave Vermeer’s small study the sheen of an image projected by the camera obscura onto a plate of ground glass or tautly stretched oiled paper. More unusual than Vermeer’s choice of the panel support, however, is that he chose a previously used panel with an unfinished, bust-length portrait of a man wearing a wide-brimmed hat, which he simply turned 180 degrees.

Scientific imaging has revealed what this painting of a man looked like before Vermeer began his work on Girl with the Red Hat. Infrared reflectography shows the black pigment the artist used for the bold, rhythmic brushwork of his hat and curly hair . X-ray fluorescence imaging spectroscopy mapping the chemical element lead shows the face, whitish collar, and collar tie—all painted with substantial amounts of lead white—as well as long brushstrokes with lesser amounts of lead white in the lighted background, where they curve around the brim of the hat, and short, diagonal strokes that describe the drape of the man’s garment over his shoulder . For decades scholars have discounted the possibility that Vermeer painted this man, noting that the free and brushy style of his face is very different from the refined visages in Vermeer’s genre paintings. But Vermeer’s animated brushwork in Girl with the Red Hat means that we can no longer summarily discount the possibility of Vermeer’s authorship.

As the smallest of Vermeer’s extant paintings, the only known work on panel, and the artist’s first real venture into the schematically rendered forms of his late style, Girl with the Red Hat occupies an intriguing place in Vermeer’s oeuvre. It reveals the undiminished creativity and experimentalism with which he approached his craft and provides insight into his evolution as an artist. Yet, as a reused panel, it also reminds us of some of the mysteries left to solve regarding the scope of his work and the range of his clientele.

Technical Summary

The support is a single wood plank, probably oak, with a vertical grain. A cradle, including a wooden collar around all four sides of the panel, was attached before the painting entered the collection. A partially completed painting exists underneath the present composition oriented 180 degrees with respect to the girl. The X-radiograph reveals the head-and-shoulders portrait of a man wearing a white kerchief around his neck and a button on his garment. Infrared reflectography at 1.1 to 2.5 microns shows a cape across his shoulder, a broad-brimmed hat, locks of long curling hair, and vigorous brushwork in the background.

The panel was initially prepared with a light tan double ground. The male bust was executed in a dark brown painted sketch, before flesh tones were applied to the face and white to the kerchief. The portrait of the young girl was painted directly over the underlying composition, with the exception of the area of the man’s kerchief, which Vermeer apparently toned down with a brown paint.

The paint used to model the girl was applied with smoothly blended strokes. Layered applications of paint of varying transparencies and thicknesses, often blended wet-into-wet, produced soft contours and diffused lighting effects. The paint in the white kerchief around the girl’s neck has been scraped back to expose darker paint below.

The painting was treated in 1994 to remove discolored varnish and inpaint. The treatment revealed the painting to be in excellent condition with just a few minor losses along the edges. The painting had been treated previously in 1933, probably by Louis de Wild, and in 1942 by Frank Sullivan.

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. based on the examination report by Sarah Fisher

April 24, 2014

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913, inv. 14.40.611

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913, inv. 14.40.611

Musée du Louvre, Paris / Art Resource, NY, Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. M.I. 1448

Musée du Louvre, Paris / Art Resource, NY, Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. M.I. 1448

Photo © National Gallery of Ireland, National Gallery of Ireland, Presented, Sir Alfred and Lady Beit, 1987 (Beit Collection), NGI.4535

Photo © National Gallery of Ireland, National Gallery of Ireland, Presented, Sir Alfred and Lady Beit, 1987 (Beit Collection), NGI.4535

Musée du Louvre, Paris / Art Resource, NY, Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. RF 1983 28

Musée du Louvre, Paris / Art Resource, NY, Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. RF 1983 28

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, inv. 1149

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, inv. 1149

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.53

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.53

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.53

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.53