Baroque Twists and Turns

Material Evidence and the Network of Makers of a Seventeenth-Century Drawing of Giovanni Grosso

Publication History

Published online

Peer Review

This article has been peer-reviewed

Article DOI:

https://doi.org/testlink.1234On this Page:

Introduction

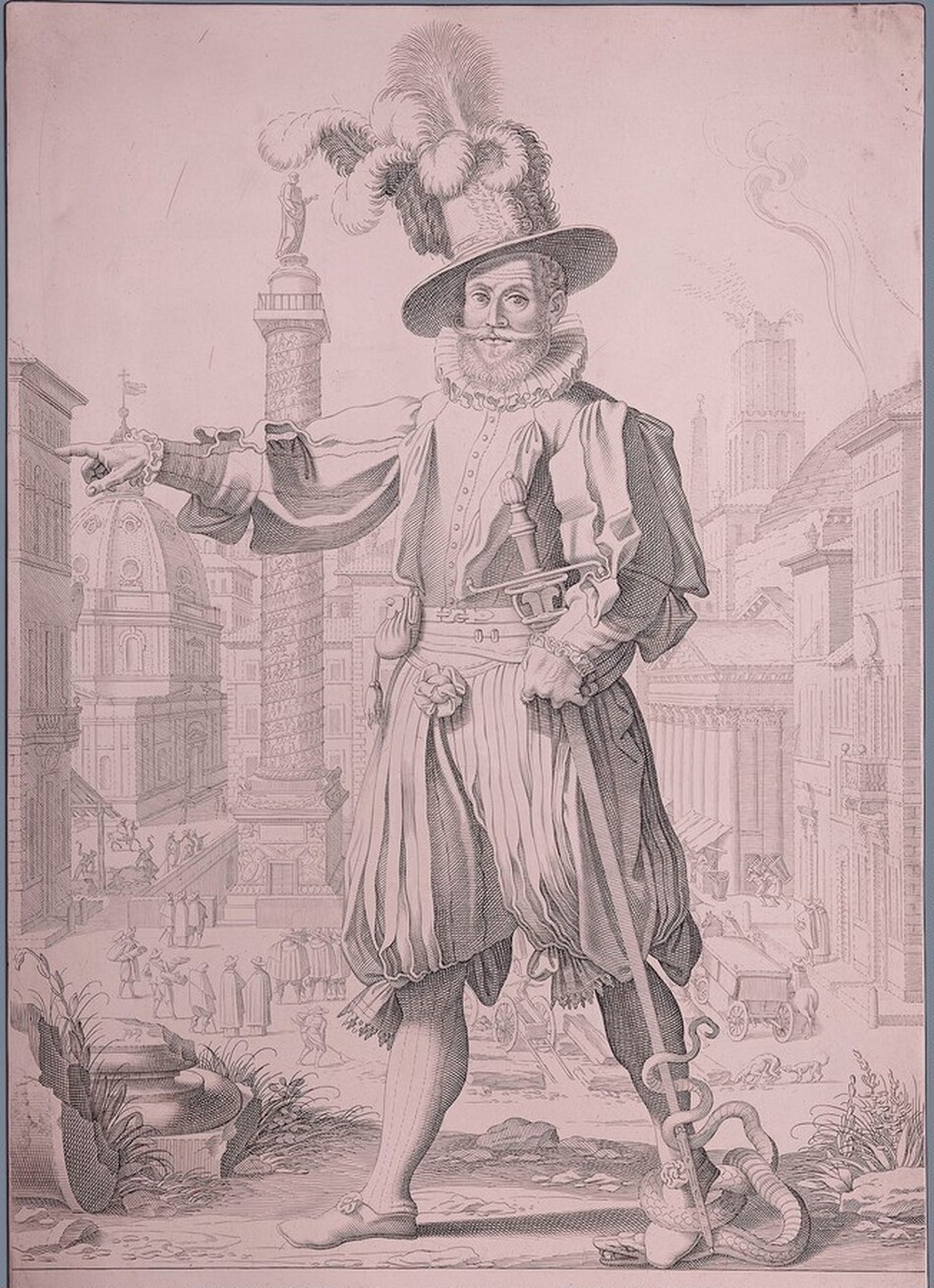

This essay explores the materials and stages of production of an early seventeenth-century drawing at the National Gallery of Art (fig. 1), bearing the marks of the many twists and turns a design may undergo, from fabrication of a print matrix to dissemination of the printed image and to subsequent copying. Presenting new technical and archival evidence, we introduce here a network of makers of art (artists, engravers, publishers) in the early 1600s who took an interest in portraits of antiquarians and tour guides such as Giovanni Grosso, the subject of the drawing. “Giovanni Grosso” is a common Italian translation of Hans Rudolph Heinrich Hoch, his given name (born 1577 in Lucerne, Switzerland; died 1660 in Rome, Italy). Grosso was a popular tour guide, or cicerone, for visitors to Rome as well as a member of the Swiss Guard. Printed images depicting Grosso’s likeness are frequently confused in catalog records across museum collections, where variants of his translated name proliferate (Giovanni Gross, Johann Groß, Giovanni Alto, Johann Alten, Ioannes Altus, Johann Hoch, Johannes Altus, Giovanni Altoviti).

Fig. 1. Swiss 17th Century after Francesco Villamena, Giovanni Grosso of the Swiss Guards Standing before a View of Rome, watercolor over black ink and graphite on laid paper, overall 32.4 × 23.1 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Arturo and Corinne Cuéllar, 2001.114.1.

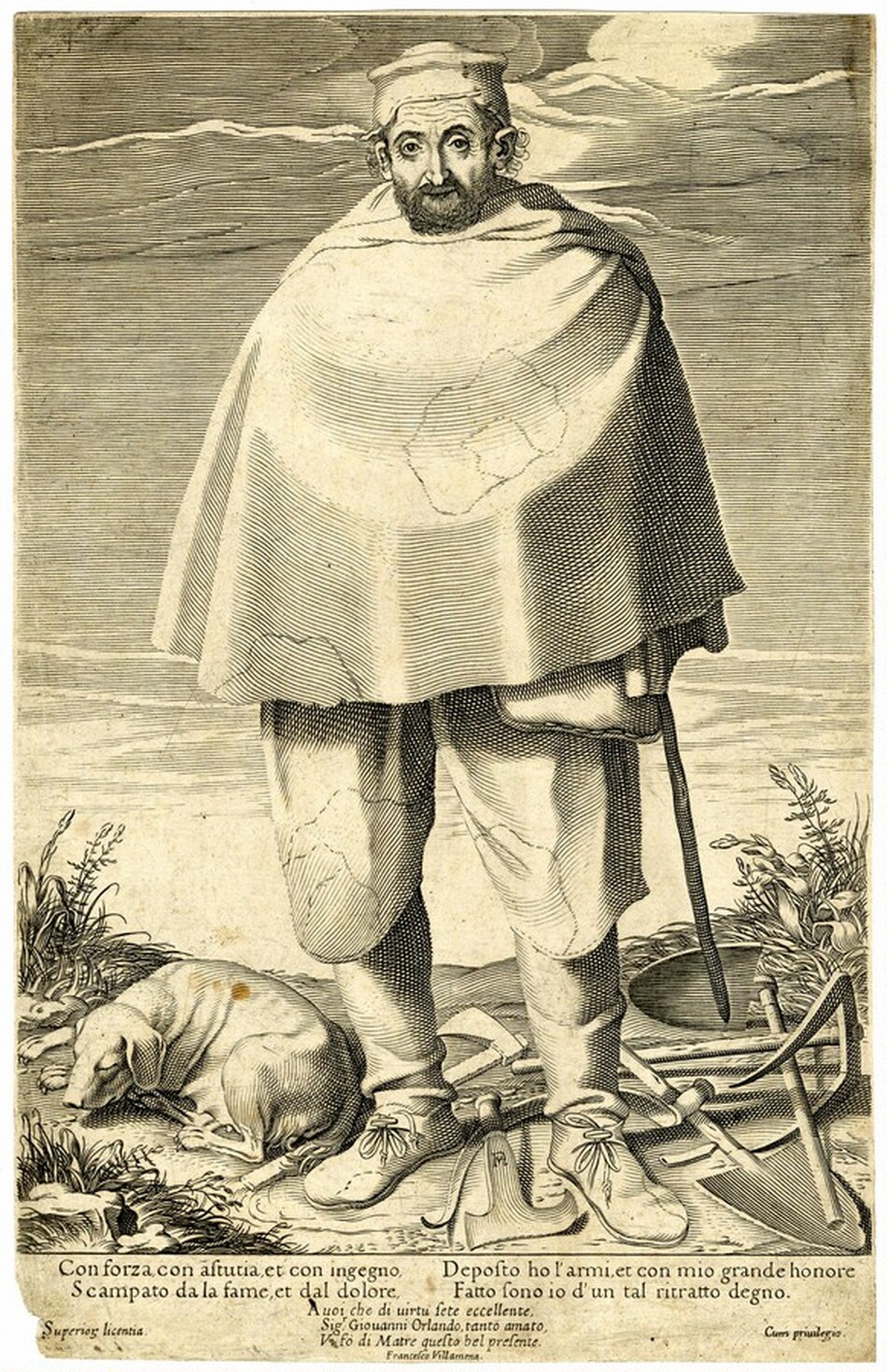

In the first part of the essay, we address the debate surrounding Grosso’s identity and his role within a network of antiquarians and travelers, as well as the role of the Italian artist Francesco Villamena (1566–1624). In the second part, we discuss the physical features of the National Gallery drawing, including the presence of lines in graphite and black ink traced from a 1613 engraving after a design by Villamena (fig. 2). Grosso’s attire, the colorful striped costume worn by members of the Pontifical Swiss Guard, is painted with blue, yellow, and red watercolors. Presenting new evidence in the form of inscriptions, color notes, and staining, we speculate on the purpose and history of the drawing. We do not offer an attribution of the National Gallery drawing to a particular hand but instead consider its role in the promotion of Giovanni Grosso to a growing tourist trade.

Fig. 2. Francesco Villamena, Johann Alten (Ioannes Altus) standing on the Quirinal with a view of Rome behind him, 1613, engraving, 375 × 232 mm, British Museum 1871,1209.2287. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Grosso’s Likeness, Identity, and Brand

According to Peter Weber, author of the most extensive biographical essay on Grosso and whose historical analysis is adopted here, the Hoch family came from what is now the Lucerne administrative district of Willisau, where it first appears in documents in 1456. Grosso’s ancestor Hans Hoch was already active as a mercenary in what is now western Switzerland and France. Grosso was born in the mid-1570s and followed in his ancestor’s footsteps by enlisting in the Pontifical Swiss Guard in Rome around 1605. He remained a guard at least until 1619 and likely until his death in 1660 at the age of eighty-three; he was buried in the Vatican’s German Cemetery (Campo Santo Teutonico). Grosso is well documented as a renowned cicerone throughout the first half of the seventeenth century. The abundant records of his activity as a guide in Rome survive in a four-volume guest book at the Vatican Library in Rome, where he is listed under the name Alto, one of two translations of Hoch: grosso (big) and alto (tall). The volumes record around 1,100 entries for people who met with Grosso spanning a forty-three-year period, from 1616 to 1659, and show that the peak of Grosso’s social activity took place in the milder seasons. In 1641, he published a guidebook under the name Giovanni Ridolfo Alto, Splendore dell’antica e moderna Roma, for his clientele, composed mostly of young men born into noble or wealthy merchant families who were embarking on a peregrinationes accademicae or Kavalierstours in the Italian Peninsula and who came from lands that today comprise Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Germany, Poland, England, the Netherlands, Russia, Spain, and France.

Despite these records, there is a lack of consensus on the question of Grosso’s identity in the art historical literature. The dispute stems from the comparative analysis put forward in the art historical discourse to elucidate the identification of two prints illustrating what is believed to be the same subject, the 1613 engraving and an engraving from 1623 (fig. 3), both by the hand of Villamena. A red and black chalk drawing related to the 1623 print is in the collection of the British Museum, London (fig. 4), while a wash and chalk drawing resides in the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg. A systematic examination of several catalog entries reveals that images of two people were at some point confused as one person, regardless of the attribution to Villamena. The identity of the person in the 1613 image has been cataloged by the many variant spellings of his surname (Hoch, Grosso, or Groß and also Alto, Alten, or Altus); for example, the engraving in the British Museum identifies the subject as “Johann Alten” (or Ionnaes Altus). In the case of the 1623 engraving, the person depicted has been confused with Grosso by catalogers describing prints trimmed at the lower edge and lacking the dedicatory inscription, which clearly identifies the person as Cassiano dal Pozzo (1588–1657).

This confusion has encouraged a scholarly debate on the identity of the subject, leading some scholars to suggest the existence of two ciceroni born in Lucerne three years apart, one named Giovanni Alto (born 1577) and the other named Grosso (born 1574), both of whom enlisted in the Swiss Guard, came from extraordinarily similar backgrounds, and died in Rome in 1660.

Inscriptions, Printed Texts, and Notations

A dedication to both Grosso and the successful commercial publisher Andrea Vachario (1573–1627) is found at the bottom of the 1613 engraving by Villamena, stating that Vacchario was an acquaintance of both the artist and the cicerone. A handwritten inscription in black ink on the back of the National Gallery drawing repeats this dedication verbatim. Because the drawing is mounted to a thick laid paper, the handwriting had until now gone unnoticed. It becomes legible only when the sheet is viewed in transmitted light (fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Verso in transmitted light of Giovanni Grosso of the Swiss Guards Standing before a View of Rome (fig. 1), showing seventeenth-century inscription on back of drawing.

The dedication on the engraving and the drawing reads:

The true Guide of the Oltramontani | Showing ancient and modern maps

I have here retracted to my natural semblance. | And the sublime buildings of the Romans.Al’ Maj.co Andrea Vachario

I have dedicated to you the portrait of Giovanni Grosso da Lucerna, soldier of Our Lord's guard, both for the friendship that exists between the two of you as well as for the many prints you have of the ancient and modern buildings of Rome. / Therefore receive it as something from a good friend and may God will help you In Rome in the year 13 F. (rancesco) Vill’amęna.

An additional engraved note in the lower left corner of the 1613 engraving reads, “si vendono dal Billy alla Chiesa Nuova” (they are sold at Billy’s, at the Chiesa Nuova). This later addition is not recorded on the back of the National Gallery drawing but can be found on second states of the print, such as the British Museum impression (see fig. 2). Impressions of an earlier state without the seller’s address are located at the Metropolitan Museum and Brown University (see Appendix).

Network of Makers, Network of Markets

The debate on the identity of the figures in the 1613 and 1623 engravings is not of secondary importance in our attempt to show that the National Gallery drawing is evidence of a flourishing market for prints, drawings, and antiquities connected to the phenomenon of tourism in Rome. The products of this incipient travel industry, based in an antiquarian and thus a humanist program, were intended for the new and commercially interested audience and offered business opportunities for a wide range of professionals—publishers, authors, artists, ciceroni—who were promoting tours with standardized routes, destinations, and logistics.

To elaborate the question of identity and the purpose of the National Gallery drawing as a marketing tool, it is crucial to examine the relationships emerging from the representations that connected Grosso, Francesco Villamena, and Cassiano dal Pozzo. As we discuss, the depictions of Grosso and the consideration of the use of the double, or crypto-portrait, brought here to the fore, reinforce Grosso’s role as Geschäftsmann, a market-oriented businessman connected to a wide network of elite individuals descending on Rome from the northern territories of the Holy Roman Empire. As Zdeněk Hojda has pointed out, a shared interest in Roman antiquities by Villamena, Grosso, and Vachario could be one reason for the dedication on the 1613 engraving. On the other hand, it could be read as a marketing tool not only for Grosso, but for all three men. As reported by Thomas Ashby, Grosso’s activities as a tour guide and de facto cultural ambassador made him a very useful person to antiquarians and erudite men, as well as print and book dealers, and ultimately Grosso became a publisher himself.

The comparative study of the drawing and the prints reproducing the 1613 iconography seems to indicate the intermediary stage of this drawing (an artifact of the design and engraving process) and perhaps speaks to a customer-client relationship. Franca Trinchieri Camiz reports that Francesco Villamena was not only an artist-engraver but also a successful collector and dealer. At the time of Villamena’s death, his inventory included various portraits instrumental for papal propaganda but also a series of copper plates depicting starkly realistic, almost grotesque characters like the street vendors he created from about 1598 to the 1600s. Oddly enough, neither the copper plate for the 1613 engraving (now at the Istituto centrale per la grafica [IGC] in Rome) nor that for the 1623 engraving (unknown location) was listed in his inventory.

The 1623 portrait can also be considered in the context of marketing and self-promotion. The inscription shows a triumvirate: Villamena, the author; Grosso, arguably the sitter; and Cassiano dal Pozzo, to whom the image is dedicated. The game of the double, a sort of burlesque amusement popular among the literati of the seventeenth century, could be at play here. Maurizio Berri and Lee Bimm have pointed out that Villamena had a predilection for it and used it in at least one previous instance. These considerations put us in agreement with Berri and Brimm, who identify the 1623 sitter not as Grosso (or Alto) but as Cassiano dal Pozzo, at the age of thirty-five, thus de facto debunking the theory of Alto and Grosso being two different individuals.

As highlighted by Weber, Cassiano and Grosso shared—at least at second glance—common interests. Grosso continued to target wealthy foreigners as customers, branding himself as the “true guide” for visitors from the northern regions, while dal Pozzo was interested in the study of Roman antiquities, which was dependent on acquiring a license to conduct excavations.

Andrea Emiliani’s studies on the legislation surrounding the market for cultural heritage in the pre-unitarian states in the Italian Peninsula report on two edicts restricting the export of antiquities issued during the cicerone’s period of activity. However, cardinals often saw exporting antiquities as a manifestation of their power and were therefore willing to disregard the domestic policy regulations of the cardinal chambers if it served their foreign policy interests. It is not possible to prove definitively that the records in Grosso’s guest books are correlated with moments of increased acquisitions of artworks in Rome by northern Europeans. This theory remains compelling, however, since winter was the season for unearthing Roman antiquities, as speculated by Barbara Furlotti. The tourists, for their part, were eager to keep some of these antiquities, whether legally or illegally. In both cases, everyone involved benefited directly or indirectly from the form of advertisement these prints seem to convey.

Beyond the stated evidence, there are many arguments that can be put forward to support this position and the use of the design to market Grosso’s brand. Three are based on visual analysis. First, the hand gesture in the 1623 portrait (see fig. 3) is more suited to an orator, someone who elucidates rather than points, as it appears in the National Gallery’s drawing (see fig. 1). We believe the nuance of this gesture was conceived by Villamena in his original drawing to distinguish Cassiano dal Pozzo from Grosso rather than assimilate the two. Such gestures are the subject of L’arte dei cenni, a popular treatise on gestures and body language published in 1616 by Giovanni Bonifacio, a jurist from Padova, and based on the classical tradition of rhetoric that might have served as a source of images for artists. Second, the clothing is quite different, one of military character and the other more suitable for a nobleman, a knight denoting a French influence. Third, as noted by T. Barton Thurber, a comparison of the landscapes in the background can also support our hypothesis, as they appear to be linked to the characters portrayed and to their possible audiences: the accuracy of the view of Rome in the 1623 engraving (see fig. 3) could be a reference to Cassiano’s erudition and therefore addressed to a scholarly audience, while the composite view of the monuments in the 1613 engraving (see fig. 2) might be linked to Grosso’s activity as a tour guide. Interestingly, a small figure with extended arm and dressed in a striped uniform stands by a fountain to the left of Cassiano and may allude to Villemena’s depiction of Grosso in the 1613 engraving.

The National Gallery Drawing

While the literature on Grosso is quite extensive, there are no studies dedicated to the National Gallery’s drawing (see fig. 1) and its relation to other works attributed to Francesco Villamena. The drawing, executed in watercolor over black ink and graphite on laid paper, corresponds to an engraving published in 1613 (see fig. 2). The copper plate is located in Rome at the ICG (fig. 6), and several printed impressions pulled from the plate are found in European and American collections (see Appendix). It is not possible to attribute the National Gallery’s drawing to Francesco Villamena’s hand, yet the fidelity of the line work to Villamena’s engraving is such that it must have been created by an individual familiar with the print produced from the ICG’s copper plate. The dimensions of the drawing (324 × 231 mm) closely correspond to those of the copper plate matrix (375 × 235 mm) when accounting for the added margin at the lower edge of the plate with a dedicatory text (approx. 50 mm in height).

Fig. 6. Francesco Villamena (artist and engraver), La vera Guida de gl’ Oltramontani, 1613, engraved copper plate, 375 × 235 mm, Istituto centrale per la grafica, Rome, M-1061_2. Image: Ministero per i Beni e le Attivita’ Culturali.

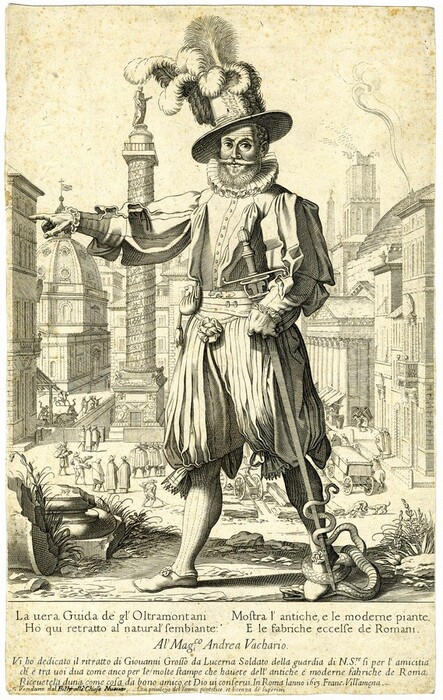

Drawings attributed to Villamena that served as designs for engravings show a looser handling of ink and shading than the National Gallery’s drawing. One example of this type of drawing is the pen and wash rendering, Study of a Bearded Man Standing with Cloak Wrapped About Him (279 × 171 mm), at the Morgan Library and Museum (fig. 7), which corresponds to an engraving executed by Francesco Villamena, A Gardener and His Dog (fig. 8).

The pattern of engraved lines is evocative of Villamena’s skill in translating designs in pen and wash to engravings made with a burin, a talent that was highly valued in the seventeenth century, such that Villamena’s contemporaries regarded him as an accomplished “painter-engraver.” The Morgan drawing lacks the distinguishing background features realized in the engraving, such as the various tools and the sleeping dog. Importantly, the orientation of the bearded man in the Morgan drawing is reversed in the print, whereas in the National Gallery’s drawing Grosso faces in the same direction as the engraving, one indication that our drawing might have been traced directly from a print.

Although the drawing’s surface is abraded and worn, an extensive graphite underdrawing remains visible below the carbon black ink pen lines. The graphite lines define Grosso’s features and the setting, including details of the buildings and the tiny figures in the distance. The ink lines reinforce the lighter graphite marks (fig. 9). Both the graphite and the ink lines lack the naturalness of an original sketch and instead exhibit a uniform, deliberate appearance as if they were traced from another source, most likely from a print taken from the 1613 copper plate. Distinct from the colors of the Swiss Guard uniform, the gray wash additions to the National Gallery drawing allude to the three-dimensional forms that would be developed in parallel hatched and cross-hatched lines on the copper plate by a professional engraver. The broken column at the bottom left differs somewhat from the rest of the drawing in its execution and appears casually drawn but not traced. The fallen section has an ambiguous shape drawn only with pen, and some graphite squiggles allude to the jagged cracks of the stone. In addition, Grosso’s beard lacks definition in either graphite or ink.

Fig. 9. Detail of Giovanni Grosso of the Swiss Guards Standing before a View of Rome (fig. 1), showing traced graphite and ink lines and gray wash.

The order in which these materials were applied, in the aggregate, is characteristic of a drawing prepared before the design was engraved. However, it is more likely that the National Gallery drawing was traced from an engraving in order to create another matrix, a practice related to the use of copies or replicas “for which a tracing created from a fresh print was used and transposed onto a new plate.” As Grelle Iusco explains, this practice was implemented not only to satisfy the high demands of the market but also to limit the wear and tear of matrixes, which were highly valued in the printing business primarily for their functionality. The proliferation of prints and other media that relate to the 1613 Villamena matrix supports these assumptions (see Appendix).

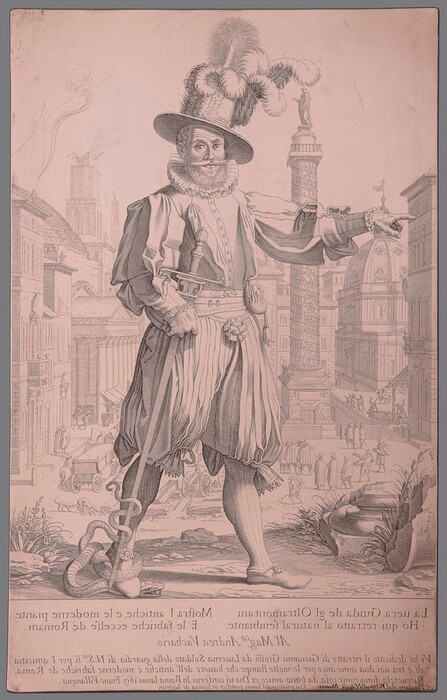

Other prints depicting Grosso in the same environs are from an undated plate executed and signed by Henry Le Roy (1579–1652), with the dedication at the bottom written in French (fig. 10). The design is copied from Villamena’s 1613 print, and thus the image created by Le Roy is reversed. In fact, Le Roy acknowledges Villamena’s design with an inscription placed between the feet of Giovanni Grosso, “F. Villamena inv.” Although the technical relationship between the National Gallery drawing and Le Roy’s undated print remains unclear, there is a possibility that the two are somehow related. The watermark present on the drawing is obscured by a dense, modern laid paper adhered to the verso and has not been found in sources picturing known watermarks. Visible features indicate the watermark is an elongated coat of arms similar to the Strasbourg bend, centered on one chain line and between two others.

Fig. 10. Henri Le Roy (publisher), Francesco Villamena (designer), La vraye Guide de l’Oltremontain, no date, engraving, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie, RESERVE QB-201 (29)-FOL.

The condition of the paper sheet bears evidence of its possible presence in a printing workshop. In addition to the black drawing ink used extensively in the figure and background, a very small smear of a second black ink is observed on the surface of the drawing, just below the statue of St. Peter the Apostle on Trajan’s Column. Microscopic examination reveals an ink of more viscous consistency, which may be printing ink transferred from another surface while the drawing was handled in an active print shop. A series of stains, likely oil, lies parallel to the bottom of the paper sheet, providing further evidence that the drawing was present in a busy engraving workshop or a painter’s studio.

Grosso’s colored uniform is a primary feature of the drawing, yet also a puzzle to interpret. The vibrant stripes of red, yellow, and blue are representative of the characteristic uniform of the Pontifical Swiss Guard, the uniform invariably worn by Giovanni Grosso. Extensive color notes inscribed across the figure’s costume designate where washes of color were to be applied. The notes are written as minuscule letters, “R,” “B,” “G,” and “W,” along with the single word, groß, above the brim of the man’s hat (fig. 11), most likely referring to Grosso’s name rather than the word’s other meanings, “tall” or “big.” No color is observed on the sheet corresponding to the letter “W,” placed near plumage atop the hat. This single letter “W” suggests these notes correspond to the German or Dutch words weiss/wit (white), rot/rood (red), blau/blauw (blue), and gelb/geel (yellow). The purpose of the coloring in the National Gallery drawing is unclear, especially since no hand-colored impressions of Villamena’s 1613 engraving or those published later by Le Roy have been located. When a publisher wants to offer hand-colored impressions, an artist typically applies paint to a printed proof that acts as the example for colorists to follow when subsequently applying watercolor to the printed edition. For this reason, hand-colored print impressions are generally priced higher than uncolored ones.

Fig. 11. Detail of Giovanni Grosso of the Swiss Guards Standing before a View of Rome (fig. 1), showing the initial “W” for weiss (white) at the center top and the word groß at center, above the brim of the hat.

Conclusion

Working drawings and related types of material showing the intermediate stages of designs for etchings and engravings are a vanishing body of evidence. If a definitive attribution of authorship for the National Gallery’s drawing cannot be put forward at this time, the analysis of material evidence, such as the handwritten inscription on the verso, the oil stains, and the lack of significant alterations from the copper plate, allows us to suggest that this drawing is an intermediary work that reveals the process of translating a design from one etching to another. This drawing thus is witness to the changing of a design as it traverses workshop environments, beginning with a tracing from an impression of Francesco Villamena’s print. Even with the observations and new evidence provided here, there is not yet enough information to understand the entire process of creation of the National Gallery’s drawing, but it is better understood within a complex series of stages and transfers of original design ideas across media, sometimes ephemeral in nature.

The proliferation of images of Giovanni Grosso after Villamena’s 1613 print and the proposed resolution of the identity debate involving Grosso, Alto, and Hoch shed light on the processes of printmaking in the public sphere of business and social transactions (tour guides, antiquarians, academicians). In the context of this essay, the use of the double, or crypto, portrait appears then as a means of facilitating, or at least advertising, a network of tourism linked also to the antiquities trade, a more or less sanctioned “crypto world” composed of wurmschneiders (lit. “worm-cutters,” referring to tour guides), erudite men, noblemen, artists, cardinals, and workers.

We have presented evidence that the National Gallery’s drawing is not related to the production of the 1613 engraved plate but instead is a tracing of a print taken from that plate, probably to produce another plate. The copying of the dedication from the bottom of the engraving onto the back of the drawing in pen suggests that the new plate would include the same inscription, or some derivative or translation thereof, as well as the image. The smear of what is possibly printing ink and the oil stains near the figure’s legs place the drawing in a workshop, either to produce a second plate (such as the engraving later published by Henri Le Roy) or to experiment on a third plate that was not realized. The possibility of a third plate cannot be discounted, especially considering that Giovanni Grosso himself published plates, among them plates that appear in his guidebook, Splendore dell’antica e moderna Roma, that he obtained from the estate of Giacomo Lauro. Grosso may have contemplated the 1613 image as a means of advertisement or self-promotion. It is our hope that the new evidence and observations on historical context presented here will encourage further research leading to a better understanding of how the National Gallery drawing fits into the bigger picture of business and social transactions among tour guides and antiquarians in the public sphere.

Appendix

| Collection | Inventory number | Attribution | Date | Given title | Print state | Medium | Collection or reference URL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Istituto centrale per la grafica, Rome (fig. 6) | M-1061_2 | Villamena | 1613 | Giovanni Grosso da Lucerna, Guarda Pontifica | n/a | copperplate matrix | https://www.calcografica.it/matrici/inventario.php?id=M-1061_2 |

| Istituto centrale per la grafica, Rome | S-FC31281 | Villamena | 1613 | Ritratto di Giovanni Grosso | 1 | https://www.calcografica.it/stampe/inventario.php?id=S-FC31281 | |

| Metropolitan Museum, New York | 2012.136.398 | Villamena | 1613 | Giovanni Alto (Johann Alten, Ioannes Altus) standing on the Quirinal Hill in Rome, with his right arm outstretched | 1 | https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/397591 | |

| Brown University, Providence | PSMP1613mf-1 | Villamena | 1613 | Giovanni Grosso da Lucerna Soldato della guardia di N. Sre | 1 | https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:230892/ | |

| British Museum, London (fig. 2) | 1871,1209.2287 | Villamena | 1613 | Johann Alten (Ioannes Altus) standing on the Quirinal with a view of Rome behind him | 2 | https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1871-1209-2287 | |

| Philadelphia Museum of Art | 1985-52-591 | Villamena | 1613 | The Roman Antiquarian—Giovanni Grosso (The Swiss Guard Hans Gross from Lucerne) | 2 | https://www.philamuseum.org/collection/object/29152 | |

| Národni Galerie v Praze (Prague) | sign. R 79757 | Villamena | 1613 | Giovanni Grosso come la guida sul Foro Traiano (cited Hojda 2009) | 2 | ||

| Galleria degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Designi e delle Stampe, Florence (fig. 10) | 1598 s.s. | after Villamena | after 1613 | Giovanni Grosso da Lucerna | n/a | ||

| Bibliothèque nationale de France, département estampes et photographie, Paris | RESERVE QB-201 (29)-FOL | after Villamena | after 1613 | La vraye Guide de l'Oltremontain icy portraict au naturel monstre l'anticque et moderne plan de la fabricque eslevée de Rome | n/a | https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8403192k | |

| National Gallery of Art, Washington (fig. 1) | 2001.114.1 | Swiss 17th century, after Villamena | 17th century | Giovanni Grosso of the Swiss Guards Standing before a View of Rome | n/a | drawing | https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.118724.html |

| ZHB Luzern Sondersammlung, Eigentum Korporation Luzern | n/a | unknown | no date | Johann Groẞ | n/a | painting | https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q112561480 |

Acknowledgments and References

The inscription written on the reverse of the sheet was observed by Matthew Westerby, Fulvia Zaninelli, Brooks Rich, and Peter Lukehart and transcribed by Matthew Westerby, Fulvia Zaninelli, and Peter Lukehart. Kimberly Schenck carried out examination of the work with optical microscopy and ultraviolet light to identify the presence of graphite, multiple inks, oil stains, and other material evidence. Sarah Purnell took transmitted light images and created a tracing of the visible portions of a watermark, which remains unidentified. Michelle Stein took x-radiographs, transmitted light images, and infrared images of the paper sheet. Fulvia Zaninelli located previously untraced literature and related artworks. Matthew Westerby, Fulvia Zaninelli, and Kimberly Schenck coordinated the project, in addition to writing the essay.

The authors are indebted to Brooks Rich for generous insights and observations and wish to thank Peter Lukehart for encouraging the initial research interest.

Agosti, Farinella, and Simoncini 1988

Agosti, Giovanni, Vincenzo Farinella, and Giorgio Simoncini. La Colonna Traiana e gli artisti francesi da Luigi XIV a Napoleone I: [mostra] Villa Medici, 12 aprile–12 giugno 1988. Rome, 1988.

Amendola 2020

Amendola, Adriano. “Giovanni Alto non è Giovanni Grosso: Nuove considerazioni sui ciceroni svizzeri di Lucerna e ‘l’ Antiquae Urbis Splendor’ di Giacomo Lauro.” Bollettino d’Arte 47–48 (2020): 179–190.

Ashby 1927

Ashby, Thomas. “Un incisore antiquario del Seicento (Continuazione).” La Bibliofilía 29 (1927): 356–369.

Berri and Bimm 2002

Berri, Maurizio, and Lee Bimm. “Villamena pittore? Un contributo al dibattito all aluce di nuove scoperte.” Bollettino d’Arte 120 (2002): 79–92.

Bonifacio 1616

Bonifacio, Giovanni. L’arte de’ cenni con la quale formandosi fauella visibile, si tratta della muta eloquenza, che non è altro che un facondo silentio: Diuisa in due parti . . . di Giouanni Bonifaccio giureconsulto, & assessore: L’opportuno academico filarmonico. n.p., 1616.

Borroni 1968

Borroni, Fabia. “Nicola Billy, Il Vecchio.” In Dizionario biografico degli Italiani, vol. 10 (1968). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/billy-nicola-il-vecchio_(Dizionario-Biografico) (accessed May 6, 2024).

Briquet 1985.

Briquet, C. B. Les Filigranes Dictionaire Historique des Marques du Papier. New York, 1985.

Bury 2001

Bury, Michael. The Print in Italy. London, 2001.

Emiliani 1978

Emiliani, Andrea. Leggi, bandi e provvedimenti per la tutela dei beni artistici e culturali negli antichi stati italiani 1571–1860. Bologna, 1978.

Etheridge 2007

Etheridge, Christopher Blair. “Francesco Villamena and the Art of Engraving in Counter Reformation Rome.” PhD dissertation, Cambridge, MA, 2007.

Furlotti 2019

Furlotti, Barbara. Antiquities in Motion: From Excavation Sites to Renaissance Collections. London, 2019.

Galerie Fischer 1999

Galerie Fischer. Kunstauktion: In und ausländischen Sammlungen und Nachlässen sowie aus der Slg. Otto Markés, Basel: Gemälde, Zeichnungen, Aquarelle, Druckgraphik, alte Bücher, Schweizer Kusnt 16. bis 20. Jahrhundert, Möbel, Skulpturen, Kunstgewerbe, Silber und Schmuck. Lucerne, 1999.

Grelle Iusco 1996

Grelle Iusco, Anna, and Lorenzo Filippo de’ Rossi. Indice delle stampe intagliate in rame a bulino e in acqua forte esistenti nella stamperia di Lorenzo Filippo De’ Rossi: Contributo alla storia di una stamperia romana. Rome, 1996.

Grelle Iusco 1998

Grelle Iusco, Anna. Matrici metalliche incise: Il problema della conservazione e restauro dalla calcografia romana all’Istituto nazionale per la grafica. Rome, 1998.

Heawood 1969

Heawood, Edward. Watermarks, Mainly of the 17th and 18th Centuries. Hilversum, 1969.

Hojda 2009

Hojda, Zdeněk. “Giovanni Grosso da Lucerna. La vera Guida de gl’Oltramontani: Un cicerone nella Roma del Seicento e i suoi clienti boemi.” In Roma – Praga / Praha – Řím: Omaggio a Zdeňka Hledíková, Bollettino dell’Istituto Storico Ceco di Roma 1 (2009): 219–247.

Lauro 1612

Lauro, Giacomo. Antiqvae vrbis splendor: hoc est praecipva eivsdem templa; amphitheatra, theatra, circi, navmaechiae, arcvs trivmphales, mavsolea aliaqve svmptvosiora aedificia, pompae item trivmphalis et colossaervm imaginvm descriptio. Rome, 1612.

Leuschner 1998

Leuschner, Eckhard. “The Papal Printing Privilege.” Print Quarterly 15 (1998): 359–370.

McGrath 2000

McGrath, Thomas. “Color and the Exchange of Ideas between Artist and Patron in Renaissance Italy.” Art Bulletin 2 (2000): 298–308.

Solinas 1989

Solinas, Francesco. Cassiano dal Pozzo: Atti del Seminario internazionale di studi. Rome, 1989.

Solinas 2000

Solinas, Francesco. I segreti di un collezionista: Le straordinarie raccolte di Cassiano dal Pozzo 1588–1657: Roma, Galleria nazionale d’arte antica, Palazzo Barberini, 29 settembre–26 novembre 2000. Rome, 2000.

Stenhouse 2005

Stenhouse, William. “Visitors, Display and Reception in the Antiquity Collection in Late- Renaissance Rome.” Renaissance Quarterly 58 (2005): 397–434.

Thurber 2003

Thurber, Barton T. “Multiple Personalities in Francesco Villamena’s Portrait Print of Giovanni Alto Dedicated to Cassiano dal Pozzo.” Word & Image 19 (2003): 100–114.

Trinchieri Camiz 1994

Trinchieri Camiz, Franca. “The Roman ‘Studio’ of Francesco Villamena.” Burlington Magazine 136 (1994): 506–516.

Tschudi 2012

Tschudi, Victor Plahte. “Ancient Rome in the Age of Copyright: The Privilegio and the Printing Reconstruction.” Act ad Archeologiam et Artium Historia Pertinentia 15 (2012): 177–194.

Tschudi 2016

Tschudi, Victor Plahte. Baroque Antiquity: Archeological Imagination in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge, 2016.

von Schwager 2000

Schwager, Klaus von. Hans Hoch Der Wurmschneider: Ein cicerone im schatten Cassiano dal Pozzo, in Bau + Kunst: Festschrift zum 65. Geburstag von Professor Jurgen Paul. Edited by Gilbert Lupfer and Konstanze Rudert. Dresden, 2000.

Weber 2006

Weber, Peter Johannes. “Giovanni Alto: Gardist, Fremdenführer und Geschäftsmann.” In Hirtenstab und Hellebarde: Die Päpstliche Schweizergarde in Rom 1506–2006, 157–197. Zurich, 2006.

Zonghi and Zonghi 1953

Zonghi, Aurelio, and Augusto Zonghi. Zonghi’s Watermarks. Monumenta chartae papyraceae historiam illustrantia, 3. Hilversum, 1953.