Italian Paintings of the Sixteenth Century: Venus and Adonis, c. 1540s/c. 1560-1565

Publication History

Published online

Entry

Even more than in the case of the Venus with a Mirror, the Venus and Adonis was one of the most successful inventions of Titian’s later career. At least 30 versions are known to have been executed by the painter and his workshop, as well as independently by assistants and copyists within the painter’s lifetime and immediately afterward. The evolution of the composition was apparently highly complex, and scholars remain divided in their interpretation of the visual, technical, and documentary evidence. While there is general agreement that the Gallery’s version is a late work, dating from the 1560s, there is much less consensus regarding its quality and its relation to the most important of the other versions.

The subject is based on the account in Ovid, Metamorphoses (10.532–539, 705–709), of the love of the goddess Venus for the beautiful young huntsman Adonis, and of how he was tragically killed by a wild boar. But Ovid did not describe the last parting of the lovers, and Titian introduced a powerful element of dramatic tension into the story by imagining a moment in which Venus, as if filled with foreboding about Adonis’s fate, desperately clings to her lover, while he, impatient for the hunt and with his hounds straining at the leash, pulls himself free of her embrace. The goddess’s gesture is echoed by that of Cupid, who, clutching a dove—a creature sacred to Venus—anxiously watches the lovers’ leave-taking. It is usually assumed that this new conception of the story was the painter’s own idea, and in 1584 he was explicitly criticized by the Florentine Raffaello Borghini for his lack of fidelity to the ancient literary text. Some scholars have suggested that in this respect Titian was following modern literary retellings, for example the Fábula de Adonis by the imperial ambassador to Venice in the early 1540s, Don Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, or by the Venetian Lodovico Dolce in the later 1540s. But Miguel Falomir and Paul Joannides have argued that, on the contrary, such texts could well have been inspired by their authors’ knowledge of the invention by Titian, which itself is more likely to have been inspired by visual sources. They identify one such source as Marcantonio Raimondi’s engraving Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife, after Raphael’s fresco in the Vatican Loggia, in which a young man similarly escapes the amorous advances of an older woman. As first recognized by Erwin Panofsky, another important visual source for Titian’s composition—although in this case not for the novel interpretation of the myth—was the so-called Bed of Polyclitus, an antique relief known in a number of versions and copies. Panofsky focused in particular on the representation of a twisting female figure from the back, but subsequent scholars have also noted the resemblance of Adonis’s left arm to the dangling arm of sleeping Cupid in the relief.

The many versions of the composition fall into two main groups, which were respectively dubbed Groups A and B by Panofsky, and the “Prado” and “Farnese” types by Harold Wethey. The former type takes its name from the picture in the Prado, Madrid , which Titian painted in 1553–1554 for Prince Philip of Spain (from 1556 King Philip II). Other important versions of this type include those in the National Gallery, London; in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; formerly in the collection of Patrick de Charmant, Lausanne; and in a recently discovered example now in a private collection, Moscow. The format of these pictures, although they are all wider than they are tall, is close to square; Adonis has three dogs; Cupid is shown asleep under a tree in the right background; and Venus is again represented in her swan-drawn chariot in the sky. While the Prado painting is universally accepted as the finest example of the type, both the ex-Charmant and the Moscow versions have also sometimes been claimed to precede it. By contrast, the Gallery’s picture, like the version in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York , is broader and lower in its proportions than Panofsky’s Type A; Adonis has only two dogs; Cupid is awake and close to Venus; and the sky is filled with a rainbow and a burst of light. Wethey called this the “Farnese” type, because he argued that both of these pictures—as well as all the examples of the “Prado” type—were preceded by a painting formerly in the Farnese collection in Rome, Parma, and Naples, now lost, but recorded in an engraving of 1769 by Robert Strange, in which the composition was reproduced in reverse. This lost version was recorded by Carlo Ridolfi in 1648 at Palazzo Farnese in Rome and in a succession of Farnese inventories, beginning in 1644, and the writer implied that Titian painted this version for the pope’s grandson Ottavio Farnese on his visit to the papal capital in 1545–1546, together with the first version of the Danaë (Capodimonte, Naples). Although Ridolfi was certainly incorrect in saying that the Danaë was also commissioned by Ottavio, rather than by his elder brother Cardinal Alessandro, it does not necessarily follow that he was also wrong about the Farnese Venus and Adonis. There remains, in any case, a certain amount of circumstantial evidence in favor of Wethey’s hypothesis that this picture was painted for the Farnese family in the mid- or late 1540s, and critics who accept it include Fern Rusk Shapley, Rona Goffen, David Rosand, and (with reservations) Falomir and Joannides. As documented by a famous letter of 1554, Titian conceived the Venus and Adonis for Philip of Spain as a pendant to a second version of the Danaë, painted for him a year or two earlier; and since the latter is clearly based on the Farnese Danaë, there is some logic in supposing that it, too, had an original pendant in the lost Venus and Adonis. And in the following century, at least, the Farnese Venus and Adonis came to be regarded as one of a pair with the original Danaë, as is evident from the Farnese inventory of 1680, which records the two hanging together.

Yet against Wethey’s hypothesis is the simple fact that there is no mention of any Venus and Adonis in any of Titian’s extensive correspondence with Cardinal Farnese and his agents in the later 1540s. Nor does Giorgio Vasari, who was in Rome at the time of Titian’s visit, and who discusses the Danaë at length, refer to any pendant, and the Farnese version is not mentioned in any document before the inventory of the Palazzo Farnese of 1644. Further, as argued by Nicholas Penny, not only is the Venus and Adonis not a particularly happy complement to the Danaë in terms of its composition, but even more conclusive is Penny’s argument from the visual evidence that the lost Farnese picture, as recorded in Strange’s engraving, actually postdated both the Washington and the New York examples of the type, both of which are always dated for stylistic reasons to the 1560s. It is likely, therefore, either that one of the Farnese brothers ordered it from Titian at some time after circa 1565; or that it was acquired by some later member of the family, at some date before 1644.

The likelihood that Wethey’s name for this type is a misnomer does not, however, prove that Titian invented it only in the 1560s or that it must postdate his invention of the “Prado” type. Joannides and Penny have separately observed that the composition of the “Farnese,” or “two-dog,” type is more satisfactory than that of the “Prado,” or “three-dog,” type, and that for visual reasons it is more logical to interpret the latter as an expansion of the former, than the former as a simplification of the latter. Penny pointed out that the concentration of the figures more tightly into the picture field, without being diluted by landscape, is dramatically more effective. Joannides, in a series of articles, has argued that the “two-dog” type began with a now-lost composition reflected in a picture once in the Arundel collection, and destroyed in Vienna in World War II, of which there exists a miniature copy of 1631 by Peter Oliver (Burghley, Stamford) . This composition was appreciably more static and less dramatic than in later versions of the type, including the Gallery’s picture, and the foremost of the dogs was shown standing still and looking back toward its master. Not quite ready for the hunt, Adonis was shown with his right arm around Venus’s shoulder, instead of holding a spear. To judge from a prewar photograph of the ex-Arundel picture, it was not of high artistic quality, and it was apparently itself a workshop version of a lost autograph prototype. Joannides argued that both this lost original and the ex-Arundel picture were painted as early as the later 1520s and that the former was perhaps painted for Titian’s most important patron of the period, Alfonso d’Este. His principal reasons were that the poses of the pair of dogs were strikingly similar to those of the two cheetahs in the Bacchus and Ariadne (National Gallery, London) and that the color scheme, as transmitted by Peter Oliver’s copy, resembled that of the other mythologies painted for Alfonso between 1518 and 1523. Against this it may be argued that the thickset anatomy of Adonis in the ex-Arundel picture, the apparent breadth of its handling, and Venus’s hairstyle (which resembles that of the Portrait of a Young Woman of circa 1545–1546 at Capodimonte, Naples) all make it difficult to date it to the 1520s. Nevertheless, the ex-Arundel picture and its lost prototype—in other words, the earliest not only of the “two-dog” versions but of the whole series—cannot for visual reasons plausibly be dated after the mid-1540s. Indeed, if it is conceded that Don Diego Hurtado de Mendoza’s Fábula de Adonis, written in Venice between 1539 and 1545 (mentioned previously), was inspired by it, then the prototype cannot have been painted much after circa 1543.

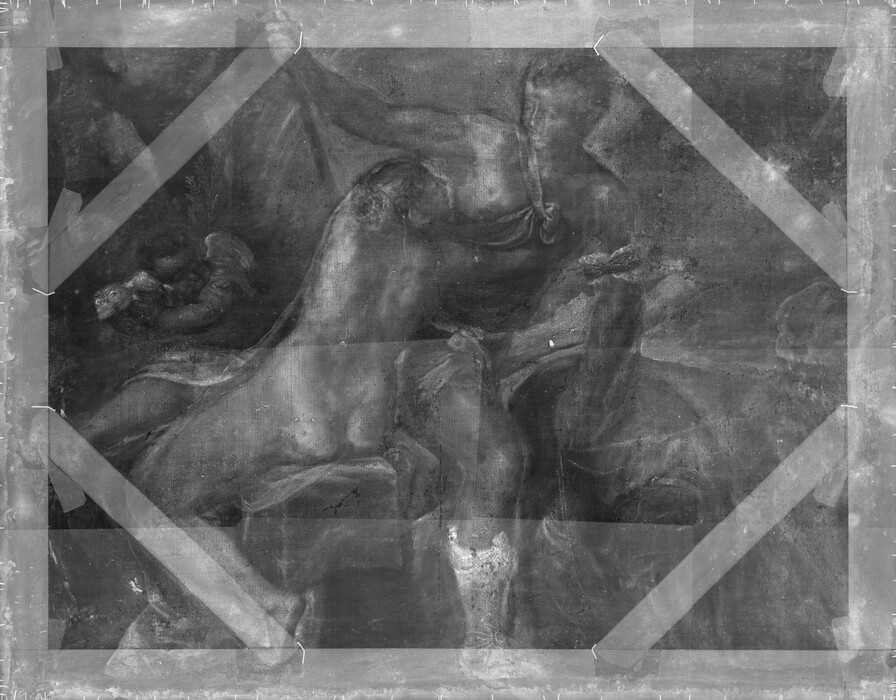

Given the likelihood of this early date, the evidence revealed by a technical examination of the Gallery’s picture undertaken in 2004 is both interesting and surprising. Most significantly, the x-radiograph and the infrared reflectogram of the latter show that the foremost dog was originally represented in a standing pose, with its head looking backward, exactly as in the ex-Arundel picture; other pentimenti corresponding to this composition include the originally vertical position of one of the leashes and the drapery that originally appeared above Adonis’s proper right shoulder. In other words, the Gallery’s picture must have been begun as another version of the ex-Arundel picture—very likely in the 1540s, or anyway, before the development of the “three-dog” composition—but was then, to judge from its surface handling, set aside and not completed until the 1560s.

This technical evidence naturally also has a bearing on another problem regarding the Gallery’s picture that has been much discussed: its relationship to the New York version. While in general agreement that both of these versions of the “two-dog” composition are late works, and that both show a certain degree of workshop assistance, scholars have expressed divergent opinions about their respective chronological relationship and quality. Hans Tietze regarded the Washington version as superior to that in New York, an opinion later reiterated by W. R. Rearick. Rodolfo Pallucchini, by contrast, followed by Francesco Valcanover, Augusto Gentili, David Alan Brown, and Maria Agnese Chiari Moretto Wiel, judged the New York version to be a substantially autograph work of the early 1560s, and the Gallery’s picture to be essentially a product of Titian’s workshop. At the end of the Titian exhibition in 1990, however, the opportunity was taken by a group of scholars, including Brown and Penny, to make a direct comparison between the two pictures; and a consensus appears to have emerged that despite its abraded surface and the severely compromised state of the blues and greens, the present work is the earlier and the finer, and shows more evidence of intervention by the master. In support of this opinion, Penny has convincingly pointed to the greater tension of Venus’s arm and the greater expressiveness of her face in the Gallery’s picture; to the addition of decorative accessories in the New York picture, such as the draperies over Adonis’s shoulders and the pearls in Venus’s plaits, not present in the Washington version or in the earlier “Arundel” composition or the picture for Philip II; and to several of the pentimenti visible in the x-radiograph of the New York picture, which show changes to initial correspondences with the Washington version. Since neither picture shows the extremely broken brushwork of Titian’s very late works of the 1570s, both may be dated to the 1560s, with the Gallery’s picture perhaps dating from the first half of the decade.

The various differences of detail between the Washington and New York pictures support the observation by Pallucchini that an engraving of the composition by Raphael Sadeler II, dated 1610 , was made from the present work, probably when it was still in Venice.

Technical Summary

The picture is painted on a relatively coarse, open, plain-weave fabric, estimated to be linen, which has been lined. The tacking edges have been removed, but cusping along all four edges and the composition imply that the painting’s dimensions have not been altered.

Infrared reflectography at 1.1 to 1.4 microns

Close inspection by the naked eye suggests that the ground was applied thinly in reddish brown. The paint is freely applied with loose, confident brushwork; lighter colors are used in a full-bodied, textured manner with scumbles, while the darks are generally painted much more thinly. The red drapery was created by covering a white underpainting with a transparent red glaze. To judge from its present gray/brown color, the sky on the right was painted with smalt pigment, but it has retained its correct hue in the area to the left of Adonis, where the smalt was clearly mixed with white lead. The copper resinate greens used for the foliage have typically discolored to a dark brown.

The picture has suffered from overzealous cleanings, and the fabric is visible in many places where the paint has been abraded. During treatment undertaken in 1992–1995 extensive old retouchings and the badly discolored varnish were removed. The painting had been treated previously in 1924 and again in 1930, this time by Herbert N. Carmer.

Peter Humfrey and Joanna Dunn based on the examination reports by Catherine Metzger and Joanna Dunn and the treatment report by David Bull

March 21, 2019

© Photographic Archive Museo Nacional del Prado, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

© Photographic Archive Museo Nacional del Prado, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jules Bache Collection, 1949

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jules Bache Collection, 1949

© Burghley House Preservation Trust Limited, Burghley House, Stamford

© Burghley House Preservation Trust Limited, Burghley House, Stamford

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection

http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/fwhb/klebeband13/0149 © Universitätsbilbiothek Heidelberg, Heidelberg University Library

http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/fwhb/klebeband13/0149 © Universitätsbilbiothek Heidelberg, Heidelberg University Library