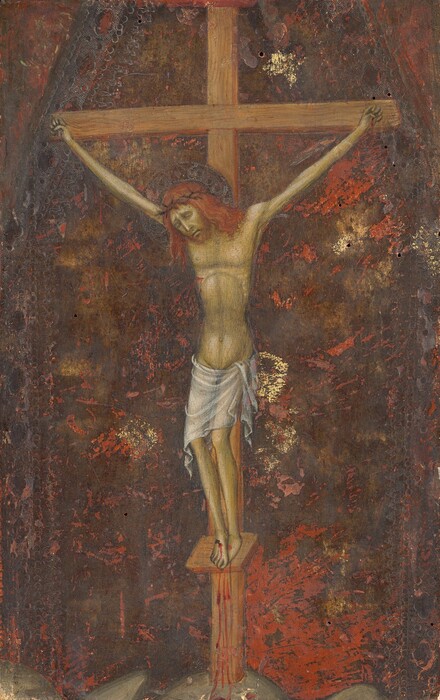

Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries: Christ on the Cross [reverse], c. 1380/1390

Publication History

Published online

Entry

The painting belongs to an uncommon genre of Byzantine origin of devotional icons painted on both sides. It is a simplified version of the portable diptych in which, as in the example discussed here, the Madonna and Child was usually represented on the

At the time of the panel’s first emergence in Florence in the 1920s, art historians expressed rather disparate views about it. Roberto Longhi, in a manuscript expertise probably dating to the years 1925 – 1930, considered the image of the Madonna likely a work of a close follower of Simone Martini, identifiable with Lippo Memmi or with Simone’s brother Donato, whereas that of Christ on the Cross on the reverse seemed to him a later addition by a painter close to Paolo di Giovanni Fei dating to the final years of the Trecento. In 1934, similar expertises were sought from other leading art historians of the time. F. Mason Perkins, followed by Giuseppe Fiocco and Wilhelm Suida, attributed it to Andrea di Bartolo;

The date of the painting, however, has given rise to considerable divergence of opinion. It was thought to have been executed by Memmi as early as c. 1330–1340 in the first catalog of the Gallery (1941). But in the later catalogs of 1965 and 1975 and in Shapley 1966 it was dated to c. 1415. In the meantime Meiss (1951) supported a dating to c. 1400, while Hendrik W. van Os (1969, 1974) offered the view that it must have been painted before the end of the fourteenth century. Shapley (1979), returning to the question, concluded that “the date may be in the 1380s.” For his part Creighton E. Gilbert (1984) seems to have favored a later dating: around 1394. Freuler (1987), van Os (1989, 1990), and Daniele Benati (1999) accepted this hypothesis, as well as Gilbert’s suggestion that the painting was commissioned by the Dominicans of the monastery of Corpus Domini in Venice, consecrated in 1394, and connected its execution to that year. In 1994, however, van Os seemed to have abandoned this position, preferring a dating to c. 1415. Bearing in mind that the connection of the panel with the Dominican nuns of Venice is purely conjectural and seems contradicted by the fact that the donor in our panel is not dressed in the habit of that order, the terminus a quo of 1394 should now be excluded from discussion of our panel.

Some help in establishing the panel’s date can, however, be derived from an analysis of its punched decoration, undertaken by Mojmir S. Frinta (1998). This scholar identified the presence in our panel of some punches already used in paintings produced in the shop of Bartolo di Fredi, as well as in youthful paintings by Andrea: I refer in particular to the polyptych in the museum at Buonconvento, probably dating to 1397, and various paintings that art historians have unanimously assigned to Andrea’s initial phase. But especially significant to me are the stylistic affinities with works by Bartolo dating to the mid-1380s or shortly after, in which signs of Andrea’s assistance can, I believe, be glimpsed: Adoration of the Magi, now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena, to which the Adoration of the Cross now divided between the museums of Altenburg and Charlottesville formerly belonged, and Massacre of the Innocents in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, probably part of the

It may be added that the composition of the Madonna of Humility evidently enjoyed considerable success. The artist replicated it many times. The example in the Gallery is likely to be one of the earliest, together with the signed version published by Berenson, its whereabouts now unknown. In the later versions the figure of Mary seems to expand to fill the painted surface, which is enclosed within an arch decorated on the inside with cusping and sometimes with figures of the Angel of the Annunciation and the Virgin Annunciate placed in medallions in the two upper corners. At the same time, the gold-tooled carpet that covers the floor is replaced by a flowering meadow; the design becomes more simplified, while the line of the hem of the Virgin’s cloak is wavier; and an increased number of angels surround the protagonists. Such late

Technical Summary

The support (contrary to Shapley 1966, 1979) is a single piece of wood, with a vertical grain and about 1 cm thick, painted on both sides. The panel has a slight convex warp relative to the obverse. It has been cut down along its upper edge. The top of the original gable is truncated, and in order to make the outer shape rectangular, triangular insets were added on both sides (approximately 1.5 cm on the top and 3 cm on the vertical edge on the left, and 1 cm along the top and 2 cm on the vertical edge on the right, as seen from the front). The original engaged frame has been lost and replaced by a modern one.

The painting was executed on the usual gesso ground, over which a thin red bole was applied in the gilded areas of the obverse. The reverse was silver gilt. An old photograph