Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries: Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Mary Magdalene and Catherine of Alexandria with Angels [entire triptych], probably 1340

Publication History

Published online

Entry

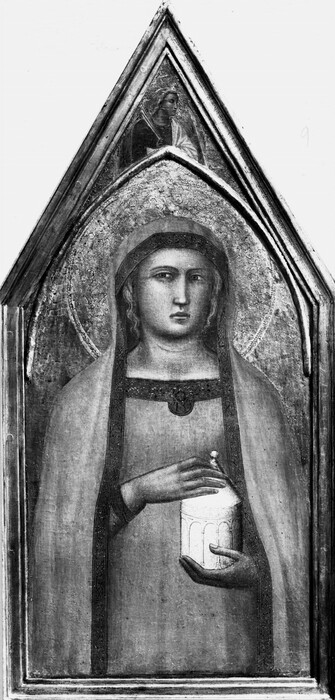

The central Madonna and Child of this triptych, which also includes Saint Catherine and Saint Mary Magdalene, proposes a peculiar variant of the so-called Hodegetria type. The Christ child is supported on his mother’s left arm and looks out of the painting directly at the observer, whereas Mary does not point to her son with her right hand, as is usual in similar images, but instead offers him cherries. The child helps himself to the proffered fruit with his left hand, and with his other is about to pop one of them into his mouth. Another unusual feature of the painting is the smock worn by the infant Jesus: it is embellished with a decorative band around the chest; a long, fluttering, pennant-like sleeve (so-called manicottolo); and metal studs around his shoulders. The group of the Madonna and Child is flanked by two female saints. The saint to the left can be recognized as Saint Mary Magdalene by the cylindrical pyx of ointment in her hand, while Saint Catherine of Alexandria is identified by her crown and by the wheel of martyrdom she supports with her right hand, half concealing it below her mantle. Both this saint and the two angels in the gable above Mary’s head bear a palm in their hand.

Though signed and dated by the artist , the triptych in the National Gallery of Art is rarely cited in the art historical literature. An impressive series of letters from experts whom Felix M. Warburg or Alessandro Contini (later Contini-Bonacossi) had consulted in 1926 about the three panels (then separately framed) confirmed their fine state, extraordinary historical importance, and attribution to Pietro Lorenzetti. Nevertheless, the panels were illustrated but cited only fleetingly in the art historical literature. For example, Ernest De Wald (1929) denied their attribution to Pietro, explaining that “the panels are evidently of Lorenzettian derivation but . . . the heads are all softer and broader than Pietro’s style. Much of this [he added] may of course be due to the clever retouching.” For his part, Emilio Cecchi (1930) included the three panels in his catalog of Pietro’s work and dedicated a brief comment to them, emphasizing that their “solemn plasticity” is typical of the painter’s last creative phase. Bernard Berenson (1932, 1936, 1968) concurred with the attribution but cited the panels as dated 1321. Raimond van Marle (1934) also accepted the attribution and Berenson’s reading of the fragmentary date. In the previous year, Giulia Sinibaldi (1933) had limited herself to citing the paintings among those ascribed to Pietro, but she took no position on the question. The triptych was ignored by most of the specialized literature in the following decades, with the exception of the successive catalogs of the Gallery itself (1942, 1965, 1968), though curiously they failed to point out the artist’s signature. Only in the catalog of 1965 was this mentioned: “a worn inscription on bottom of old part of frame of middle panel,” and the date tentatively interpreted as 1321. It was not until the 1970s that the triptych began to be regularly cited as the work of Pietro Lorenzetti (Fredericksen and Zeri 1972; Laclotte 1976) or, as in the case of Mojmir S. Frinta (1976), as the work of one of his assistants, on the basis of the punch marks that also appear in paintings by Jacopo di Mino del Pellicciaio. Frinta conjectured that the triptych could be attributable to Mino Parcis, a minor master who was apparently documented in Pietro’s shop in 1321 and was perhaps the father of Jacopo di Mino. The same scholar reassigned to Mino some works hitherto attributed to Pietro himself in his last phase and given by others to an anonymous artist called the “Dijon Master.” Fern Rusk Shapley (1979) entertained similar doubts: “Whether the attribution to Pietro Lorenzetti can be fully accepted remains somewhat uncertain.” She wondered whether the Gallery triptych might not have been a work by the same assistant of Pietro who had painted a Madonna now in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence (donation by Charles Loeser) and some other stylistically akin panels. However, Shapley cited a letter written by De Wald to Charles Parkhurst at the Gallery in 1942, reporting that he had examined the infrared photographs made during restoration at the Gallery and, on that basis, could now confirm Pietro’s hand.

After the catalog entry written by Shapley (1979), with the exception of Frinta’s volume (1998), in which the triptych continued to be classified as a product of Lorenzetti’s shop, art historians seem to have agreed that the Washington paintings should be recognized as an autograph work by Pietro himself. Those accepting this position include not only the catalog of the Gallery (NGA 1985) but also Carlo Volpe (1989), Erling S. Skaug (1994), Cristina De Benedictis (1996), Alessio Monciatti (2002), Keith Christiansen (2003), Rudolf Hiller von Gaertringen (2004), Michela Becchis (2005), Ada Labriola (2008), and Laurence B. Kanter (2010).

Bearing in mind the triptych’s state of preservation, made almost unrecognizable by inpainting aimed at concealing the damage suffered by the painted surface, it is difficult to express a balanced judgment of its authorship. Even old photographs of the panels, made prior to their latest restoration, do not assist much in that regard , , . Some of its general features—the extreme sobriety of the composition, dominated by massive figures presented in almost frontal pose and filling almost entirely the space at their disposal, and the form of the panels themselves, terminating above in a simple pointed arch—surely are those one would expect to find in the paintings by Pietro Lorenzetti in the period around 1340, when the artist was apparently fascinated by the sober grandeur of Giotto in his final phase. Undoubtedly “Lorenzettian” is the figures’ clothing, made of heavy stuff and with draperies falling perpendicularly in a few simplified or pointed folds, which barely discloses or suggests the form of the underlying body. Similar forms and compositional devices can be found in the Birth of the Virgin in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Siena, dated 1342 but commissioned and planned in 1335; the Madonna now in the Uffizi, Florence, with a provenance from Pistoia, whose fragmentary date has been variously read; and the polyptych no. 50 in the Pinacoteca Nazionale of Siena, recognized by some (if not all) art historians as executed by Pietro with studio assistance and dating to the late years of the fourth decade. Unfortunately, perhaps also because of the Washington triptych’s compromised state, the analysis of the punched ornament provides no useful indications to confirm or deny the conclusions reached by an interpretation of the stylistic data, but it should be observed that the decorative motifs of the dress of Saint Catherine are very similar to those of the cloth of honor of the Madonna in the Uffizi and seem to confirm that the two works belong to the same period.

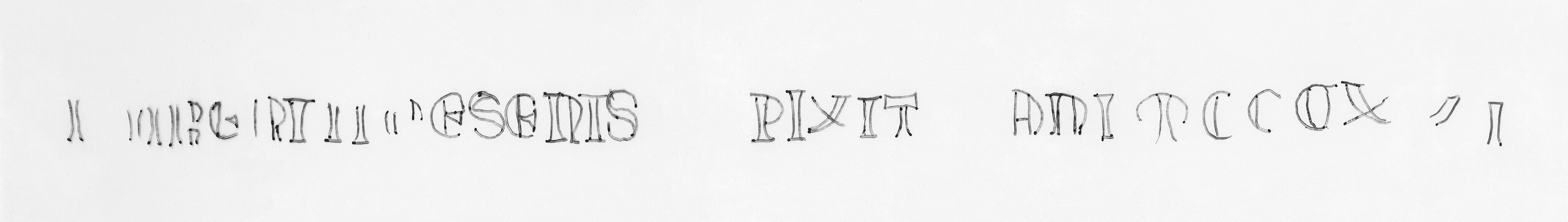

A detail that has hitherto escaped attention could offer a clue as to the triptych’s original destination: it was perhaps commissioned for a church not in Siena but in Pisa, where apparently the motif of the Christ child eating cherries was popular in the fourteenth century. Giorgio Vasari, who erroneously attributed the fresco of the Lives of the Anchorites in the Camposanto to the painter he called “Pietro Laurati” (that is, Pietro Lorenzetti), reported that the artist spent a period in Pisa, and so the unusual iconography of the central panel of the triptych might have been adopted in deference to the wishes of a patron in that city. In any case, the stylistic character seems to coincide with the evidence of the signature and the date preserved on the fragment of the original frame that has come down to us. As for the possible intervention of studio assistants, the state of preservation of the painting today prevents, in my view, speculations of this kind. Doubts perhaps can be raised about the inscription itself, because we do not know how it was recovered and inserted into the existing frame. But it is hardly probable that the signature of the artist and the date 1340 (or 1341 or 1342) would have been added to the painting by another hand, concordant with the features of this particular phase in Pietro’s career.

Technical Summary

Stephen Pichetto transferred the three parts of this triptych from the three original wooden panels to a canvas support in 1941–1942. The paintings may already have been transferred from the original wooden panels to newer panel supports in an earlier treatment as well. The current frame was made on the occasion of the 1941–1942 treatment. It incorporates a strip of wood bearing the date and artist’s signature from the original frame

(Joanna Dunn, National Gallery of Art, Washington), National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Frieda Schiff Warburg in memory of her husband, Felix M. Warburg

(Joanna Dunn, National Gallery of Art, Washington), National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Frieda Schiff Warburg in memory of her husband, Felix M. Warburg

Image: Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Frieda Schiff Warburg in memory of her husband, Felix M. Warburg

Image: Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Frieda Schiff Warburg in memory of her husband, Felix M. Warburg

Image: Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Frieda Schiff Warburg in memory of her husband, Felix M. Warburg

Image: Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Frieda Schiff Warburg in memory of her husband, Felix M. Warburg

Image: Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Frieda Schiff Warburg in memory of her husband, Felix M. Warburg

Image: Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Frieda Schiff Warburg in memory of her husband, Felix M. Warburg