Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries: Madonna and Child Enthroned with Four Saints, c. 1240/1245

Publication History

Published online

Entry

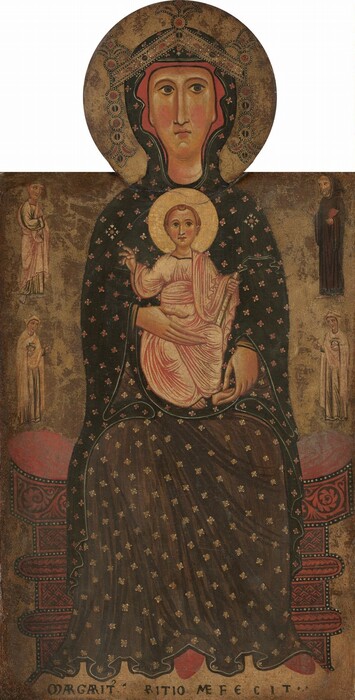

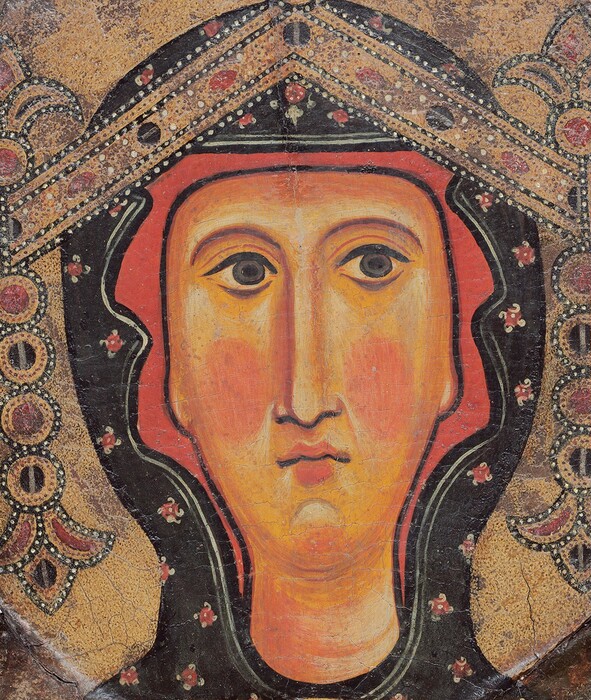

The Madonna is portrayed in a rigidly frontal position, seated on a throne without any backrest and of a shape similar to those that mainly appear in paintings of the first half of the thirteenth century. She holds the child in front of her, in a similarly frontal position. The Christ child lifts his right hand in the gesture of blessing and holds a scroll in his left, alluding to the Christian revelation. The iconography, of Byzantine origin, is known as the Virgin Nikopoios (Victory Maker). It frequently appears in the apsidal decoration of churches of the middle Byzantine period and was widespread also in panels in central Italy between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. In such paintings it was typical to present Mary, as in the image here, with the haloed head projecting upwards from the upper margin of the rectangular panel. It was also usual practice to paint golden stars on the maphorion or mantle covering her two shoulders, and often on the veil covering her head, alluding to the popular etymology of her name. The crown, on the other hand, alludes to the Marian attribute of regina coeli; it is of a particular form and decoration that often appears in the paintings by Margaritone.

In representations of similar type, the figures of saints, if present at all, always appear, as they do here, on a scale considerably smaller than that of the Virgin and child; they hover against the gold ground to the sides of the central image. They have been variously identified, but it is probable that the elderly monk in the black habit and with a book in his hand represents Saint Benedict, and that the two female saints holding lamps in their hands represent the martyrs Flora and Lucilla, whose mortal remains are venerated in the abbey dedicated to them in Arezzo. As for the youthful beardless saint facing Saint Benedict, we can do no more than conjecture: he could be the disciple preferred by Jesus, Saint John the Evangelist, as is usually suggested, but he could also be Eugenius, companion in martyrdom of the two female saints below.

It is a measure of the change in taste over the last two centuries that the panel, to which Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle and James Archer Crowe in 1886 conceded only that it is “one of the least ugly paintings left by this painter,” was hailed by Robert Lehman forty years later (1928) as “a supreme achievement of the art of the pre-giottesque period.” It was, remarked Lehman, a work in which the painter “has contributed overwhelming force and grandeur to the quiet dignity and symmetry of the Byzantine tradition,” while Ugo Galetti and Ettore Camesasca (1951) in the relevant entry of their Enciclopedia, placed it among Margaritone’s “opere più belle” (most beautiful works). As for the authorship of the work, without doubting the authenticity of the signature, some art historians have suggested that it could be a workshop variant, hence not a fully autograph painting. The date of execution is mainly placed between 1250 and 1270, though occasionally pushed back to c. 1235/1245. Such considerable variations in date are uncommon even in the study of thirteenth-century painting. To throw light on the question, let us first try to establish the relative chronology of the various versions of the Madonna painted by Margaritone and attempt on this basis to arrive at the dating of the individual works.

The stylistic affinities among the Madonna Enthroned from Montelungo (now in the Museum in Arezzo), that of the National Gallery in London, and the panel discussed here have often been emphasized. These versions are sharply differentiated from a fourth representation of the theme , the one painted for the church of Santa Maria delle Vertighe outside Monte San Savino (near Arezzo). There, not only is the child shown in three-quarter profile, but the chrysography of his garment also is used in a different way: it serves not just to embellish the figure but also to emphasize the volumetric substance of the forms. The chiaroscuro modeling of the faces also suggests that, at the time of the execution of the Santa Maria delle Vertighe panel, Margaritone was familiar with and tried to emulate certain innovative features of Byzantine neo-Hellenism disseminated in Tuscany by Giunta Pisano and other masters closely related to him around the mid-thirteenth century. The same Madonna is also differentiated from Margaritone’s other versions of the theme by the less elongated forms of the bodies and faces and the treatment of the drapery, which, instead of appearing as a kind of decorative pattern applied over the flattened forms, envelops the bodies, allowing us to glimpse the brilliant red of the lining of the Virgin’s mantle and even the shape of her throne. Moreover, in the Madonna of Monte San Savino, Margaritone abandons the archaic device of the seat as a compact block and presents us instead with a throne of more slender and more fanciful form, with the seat supported by figures of lions.

There can be little doubt, therefore, that the Madonna from Monte San Savino should be several years later in date than the others, and that they in turn are close to one another, not only in pictorial idiom but probably also in date of execution. Nonetheless, some differences can be observed among the three similar versions of the Virgin Nikopoios painted by Margaritone. The Madonna in London presents the protagonist with more robust forms than the others, and here too Mary is seated on a throne supported by lions. She is wearing a vermilion red dress, in contrast to the deep violet, perhaps intended to imitate imperial purple, in the panels in Arezzo and Washington. The diversity of the figures of the angels that flank Mary in the panels in London and Arezzo should also be noted: in the latter, the angel in the upper left, despite his similar pose, seems more static, and his forms are rendered in more summary form than in the other. I believe, in conclusion, there are grounds for deducing that the London altarpiece is more advanced in style though chronologically closer to the other two than to the panel from Monte San Savino.

Though they resemble each other closely, some differences can be observed between the paintings in Arezzo and Washington. The oval face of the Madonna is more elongated in the version in the National Gallery of Art, and the tiny figures of the lateral saints seem more rigid and the drawing of their forms more summary. In the Madonna now in Washington, moreover, there are as yet no signs of the attempts detectable in the panel in Arezzo to represent spatial depth by emphasizing the forward projection of the Virgin’s knees; he does this by the expediency of flanking areas in full light with those in shadow. In the panel discussed here the artist makes no such attempt: he essentially limits himself to the use of linear means to indicate the drapery folds. This suggests that it belongs to an earlier phase in Margarito’s career.

How can these observations be reconciled with our current knowledge of the development of Tuscan painting in the thirteenth century and with the very few dates known to us on the activity of the Aretine master? The fragmentary date of the Monte San Savino panel, which in its present state can only be read as “M.C.C.L[...]III,” has been conjecturally integrated as 1269, 1274, and 1283. The reminiscences of the manner of Giunta Pisano detectable in the painting, and the circumstance that the Pisan master, already famed in 1236, is documented only down to 1254, suggest, however, that preference be given to the date 1269. This preference becomes even more compelling if we think of the activity in Arezzo, during the seventh decade, of artists of far more advanced style than that evinced by Margaritone and Ristoro d’Arezzo. As for the dating transmitted by a seventeenth-century inscription (1250) for the Madonna from Montelungo, even if it cannot be considered as certain it seems plausible, since it would place the execution of the panel at a sufficiently wide interval from the image of Monte San Savino. Whatever the case, the analysis of the style suggests that the Washington Madonna dates to a phase preceding the panel from Montelungo. The type of the image itself as well as the stylistic data underline its kinship with works by the Sienese Master of Tressa, datable to the third decade of the century, and the Florentine Bigallo Master, whose comparable panels probably date to the years around 1230–1240. Both in his parsimonious use of shadow zones in the modeling and in his choice of the type of throne for the scene of Christ Sitting in Judgment, the painter of archaizing tendency who frescoed the cycle of the chapel of San Silvestro in the monastery of the Santi Quattro Coronati in Rome in 1246 would seem to indicate a slightly more advanced stage in stylistic development. Therefore, based on the evidence both of historical context and of a plausible reconstruction of the internal development of Margaritone’s style, it would seem that the Madonna in the Gallery probably was executed at a date close to or not long after 1240.

Technical Summary

The wooden support is formed of two panels: a larger rectangular one, made from at least two planks of vertical grain, and a smaller, roughly circular panel for the Virgin’s halo. The halo extension has a point where it attaches to the main panel. The reverse of the main panel is reinforced with a

Before the execution of the painting, the panel was covered with a fabric interleaf and a thick layer of

The silver leaf is heavily worn, and much of it appears to have been scraped away, revealing the

Image courtesy of the Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici e Paesaggistici e per il Patrimonio Storico, Artistico ed Etnoantropologico per la provincia di Arezzo, Santa Maria delle Vertighe, Monte San Savino (Arezzo)

Image courtesy of the Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici e Paesaggistici e per il Patrimonio Storico, Artistico ed Etnoantropologico per la provincia di Arezzo, Santa Maria delle Vertighe, Monte San Savino (Arezzo)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection