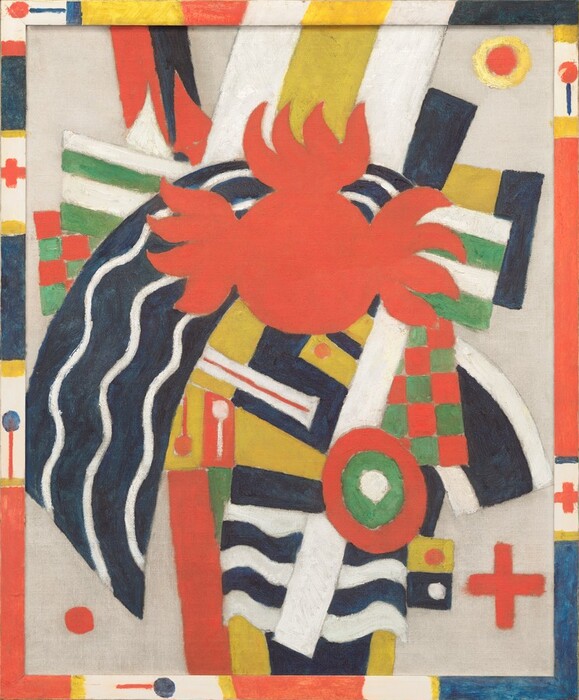

American Paintings, 1900–1945: The Aero, c. 1914

Publication History

Published online

Entry

Marsden Hartley first visited Berlin for three weeks in January 1913, accompanied by German friends that he had met in Paris. He was enchanted by the city, which he considered “without question the finest modern city in Europe,” and resolved to move there as soon as possible. The artist lived in Berlin from May 1913 to December 1915, a period interrupted only by a four-month trip to New York from November 1913 to March 1914 to raise money to support himself. Fascinated by German militaristic culture in pre–World War I Berlin, Hartley began to produce a series of paintings incorporating imagery he observed in the almost daily flow of military parades, replete with emblems, flags, and pageantry.

After returning to Berlin from his New York interlude, he embarked on the Amerika series, a set of four paintings that incorporate Native American imagery. With the outbreak of the war in August 1914, Hartley reverted to painting festive German military subjects. The tragic battlefield death of his close friend, the Prussian officer Lieutenant Karl von Freyburg, on October 7, 1914, inspired him to begin the famous 12-painting War Motif series. Many of these works, such as the well-known Portrait of a German Officer and the Gallery’s Berlin Abstraction, allude to his fallen friend through a complex set of pictorial symbols. In general, the works Hartley produced during his two-and-a-half year stay in Berlin, particularly the War Motif series, are regarded as among the finest and most original of his career. Although they earned him a degree of critical acclaim in Germany, privations such as food shortages brought about by the war forced him to return to the United States in December 1915. When 40 of the German paintings were shown at Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 gallery in April 1916, Hartley and Stieglitz downplayed the works’ celebration of Germany’s wartime pageantry to avoid the ire of a largely anti-German American public.

Hartley is thought to have completed The Aero in 1914, sometime after his return from New York and before Freyburg’s death. He mentioned such a subject as early as May 1913 in a long letter to Stieglitz. In the letter, Hartley describes how the “military life adds so much in the way of a sense of perpetual gaiety here in Berlin. It gives the stranger like myself the feeling that some great festival is being celebrated always.” He avows his intention “to establish myself in the ultra modern scheme here and this is all possible now with Kandinsky and Marc and their group.” Later in the same letter Hartley notes that he had been told: “I succeed in bringing mysticism and art together for the first time in modern art—that each canvas is a picture for itself and there the ideas present themselves after. This is my desire—to make a decorative harmony of color & form using only such color and such form as seems fitting to the subject in hand.” The artist then refers to a painting that may well have been The Aero: “I have one canvas ‘Extase d’Aéroplane’ if it must have a title—it is my notion of the possible ecstasy or soul state of an aéroplane if it could have one.”

Hartley was a keen follower of recent advances in aviation, mentioning zeppelins in three letters to Stieglitz. On a postcard of June 1913 he wrote how the “Hansa or the Victoria Luise Luftschiffs pass overhead so majestically and so close that you see people waving their handkerchiefs.” On October 18, 1913, Hartley mentioned the explosion of a naval zeppelin the previous day that had killed 27 people in Johannisthal, 10 miles outside Berlin. A year later, in a letter of June 1914, he remarked that “the Luftschiff L.V. has just passed over us here as I write—a fascinating thing which transports one somehow every time one sees any of them.”

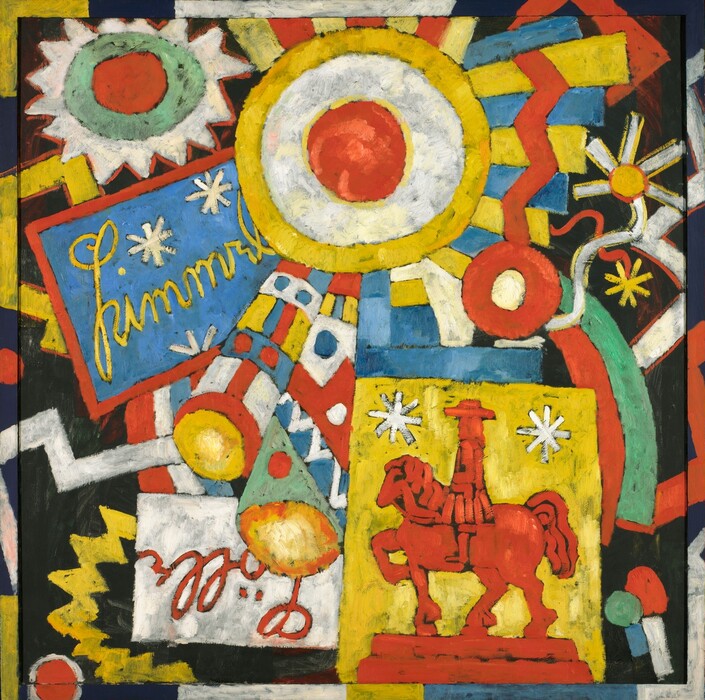

Interpreting each of the various motifs in this colorful abstract composition is difficult considering Hartley’s avowed intention to create “a decorative harmony of color & form as seems fitting to the subject in hand.” Moreover, in part because he was worried about the way the largely anti-German public would receive them, Hartley discouraged viewers from speculating about the meaning of his Berlin abstractions by claiming that “the forms are only those which I have observed casually from day to day. There is no hidden symbolism whatsoever in them; there was no slight intention of that anywhere.” It is impossible to determine whether Hartley intended The Aero to evoke either an airplane or a zeppelin, or simply embodied the two in a single image. Gail R. Scott has interpreted The Aero as an attempt to convey the “‘soul state’ of an airplane, symbolized by the red fireball of its engines and the aerial view of flags and banners signaling its flight.” Certainly the wavy motifs at the bottom center and left of the composition make one think of the artist’s description of “people waving their handkerchiefs” as a zeppelin majestically flew by. The painting adeptly conveys a sense of the exhilaration and energy that Hartley felt as he watched a large and impressive airship sail overhead.

The Aero, like most of Hartley’s Berlin paintings, reflects his close ties to the Der Blaue Reiter painters. These artists, Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter, Alfred Kubin, Paul Klee, and August Macke among them, all privileged art’s ability to convey inner subjective feelings over depicting a literal reality. Hartley was in frequent contact with Marc and Kandinsky, and had studied the latter’s book On the Spiritual in Art as well as Der Blaue Reiter Almanac. The group’s interest in the expressive decorative patterning of Bavarian folk painting probably informed Hartley’s painted frame in The Aero.

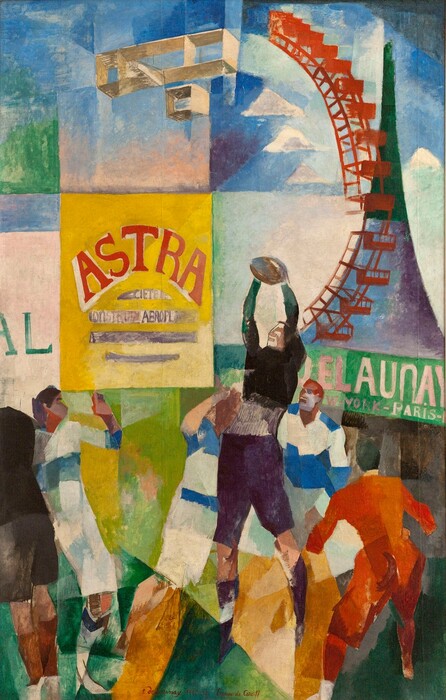

Although Der Bleue Reiter provided Hartley with the philosophical and technical means to pursue his own aesthetic desires, his fascination with aviation found its closest parallel in the French cubist Robert Delaunay. Hartley saw three of Delaunay’s most famous paintings, which all feature airplanes, around the time he was either planning The Aero or working on it. He described the huge L’Equipe Cardiff to Stieglitz after viewing it at Delaunay’s studio in March 1913 (calling it a “a perfect confession of egomania”), and saw it again later in the year at the Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon exhibition in Berlin, where it was accompanied by Soleil, Tour, Aeroplane . En route back to Berlin in March 1914, he visited Paris and attended the Salon des Indépendants, where he admired Delaunay’s L’Hommage a Blériot (Kunstmuseum, Basel), a tribute to the French aviator Louis Blériot, who had successfully flown across the English Channel in 1909.

Gail Levin has speculated that The Aero was intended as an allusion to the German Imperial Navy Zeppelin L-2 that exploded during a test flight on October 17, 1913—an accident that Hartley specifically mentioned in a letter to Stieglitz. A month earlier, another naval zeppelin, the L-1, had crashed into the North Sea 20 miles north of Helgoland Island. Both incidents were highly publicized setbacks to Germany’s military aviation program. The most plausible interpretation of The Aero is Patricia McDonnell’s suggestion that it alludes to one aspect of modern urban life in Berlin by offering “a contemplation of one of modernization’s more amazing inventions.” This idea fits well with Hartley’s fascination with the German military reflected in other works executed in 1914, such as Berlin Ante-War , Forms Abstracted, Berlin , and Himmel . After Count Zeppelin successfully flew 240 miles in one of his airships the German public was swept by “Zeppelin fever.” Kaiser Wilhelm II personally supported the idea of enhancing imperial Germany’s military prowess with the creation of an aerial fleet comprising airships and airplanes. The German military increasingly took notice of Zeppelin’s exploits and acquired airships. German writers such as Rudolph Martin had already advocated air superiority in popular novels such as Berlin-Bagdad (1907). In France, the novelist Emile Driant, influenced by Jules Verne, wrote popular and prophetic novels like L’Aviateur du Pacifique (1909) and Au-dessus du continent noir (1911) about the military deployment of airplanes.

One of the best-known novels of this genre was The War in the Air (1908) by H. G. Wells, who conjured up alarming visions of German airships destroying the American fleet in the North Atlantic and laying waste to New York City. We know Hartley was familiar with the author because, shortly after the outbreak of World War I, he discussed recent events in a letter to Stieglitz, commenting that “even H. G. Wells is a fair prophetic authority.” The development of the airplane and especially the zeppelin played an increasingly prominent part in both Germany’s military preparations and popular culture, and Hartley was an eyewitness to this progress in Berlin. Painted on the eve of World War I, the exhilarating, jubilant, and colorful Aero presents an optimistic interpretation of one of the greatest inventions of the modern era. Like a number of Hartley’s other prewar Berlin paintings that extol German military prowess, there is no indication of the imminent death and destruction that the flying machine would rain down on the cities and battlefields of Europe during World War I.

Technical Summary

The painting is executed on a plain, coarse-weave, medium-weight fabric that has been lined with wax to a plain-weave, medium-weight, auxiliary fabric support. The painting has no ground, but the fabric has been primed with a moderately thick layer of light gray paint that forms the background of the design. The exposed areas of the background paint appear to have been mixed with white before drying, altering the initial priming color, which remains its original darker gray color beneath the design elements. The main elements of the composition are applied in fairly thick, heavily textured paint. Some areas, particularly the whites and light yellow, are characterized by lively brushwork and moderate impasto. A thin layer of charcoal or black paint may be observed scumbled at the edges of many design elements, indicating that the composition was drawn before the paint was applied. An artist-constructed frame consisting of a simple wooden liner painted with an extension of the composition is attached to the painting.

The initial examination report of 1987 indicates that the painting was in good condition with numerous small, filled, and retouched losses scattered throughout. However, in a conservation treatment of the painting in 2001 it was noted that many of the major design elements had been repainted by another hand long after the completion of the painting. During this 2001 treatment, the non-original overpaint was removed, revealing some abrasion that had occurred in a previous cleaning. Although the goal of the 2001 treatment was to return the painting to its original, unvarnished state, the retouching required to compensate for previous damage and some blanching that occurred as a result of the overpaint removal necessitated locally varnishing some areas with a nearly invisible synthetic varnish. The rest of the painting was left unvarnished.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949

Image: Eric Emo / Parisienne de Photographie, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

Image: Eric Emo / Parisienne de Photographie, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

Image: Albright-Knox Art Gallery / Art Resource, NY, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, A. Conger Goodyear Fund

Image: Albright-Knox Art Gallery / Art Resource, NY, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, A. Conger Goodyear Fund

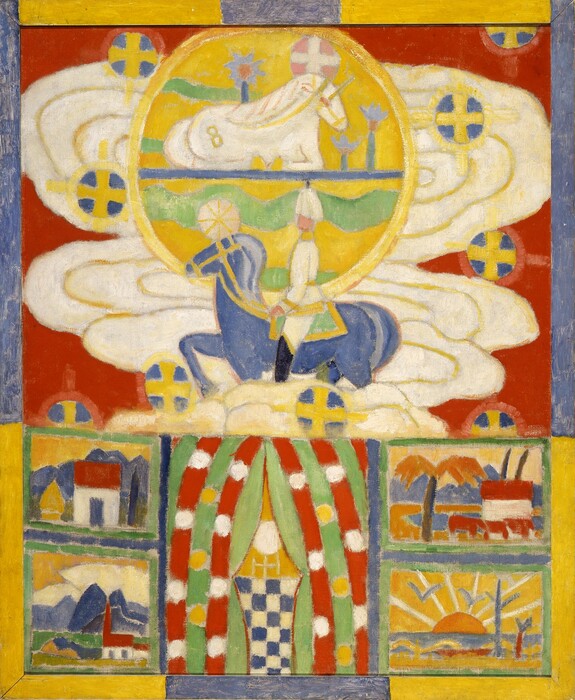

Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio, Gift of Ferdinand Howald

Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio, Gift of Ferdinand Howald

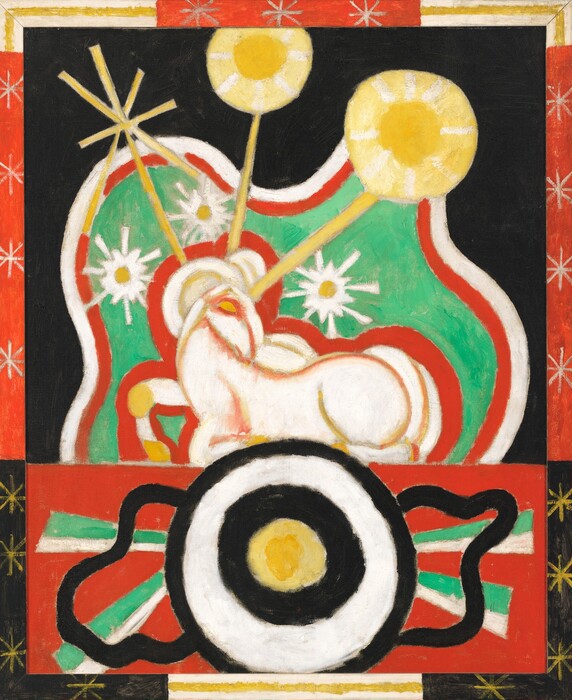

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Hudson D. Walker and Exchange 52.37a–b

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Hudson D. Walker and Exchange 52.37a–b

Image: Jamison Miller, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Gift of the Friends of Art 56-118

Image: Jamison Miller, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Gift of the Friends of Art 56-118