American Paintings, 1900–1945: Blue Morning, 1909

Publication History

Published online

Entry

From 1907 to 1909, George Bellows executed four paintings depicting the construction site of the Pennsylvania Station railroad terminal in New York City. Undertaken by the Pennsylvania Railroad under the leadership of its president, Alexander Cassatt (the artist Mary Cassatt’s brother), Pennsylvania Station (more commonly known as Penn Station) was an enormously ambitious project. Often compared with the Panama Canal, its construction was a technological feat that helped to transform New York into a thriving, modern, commuter metropolis. A tunnel had to be excavated under the Hudson River to accommodate a new electric train line that would connect Manhattan and New Jersey, and the station also facilitated travel to Long Island. The monumental terminal building, designed by the famous architectural firm McKim, Mead, & White, became the largest indoor space in New York. It comprised an impressive concourse, a waiting room inspired by the Roman Baths of Caracalla, and huge glass and steel train sheds.

The undertaking was of considerable interest to the general public, and throughout the years that Bellows worked on his paintings, newspapers and magazines regularly reported on its progress. By early July 1904, when he arrived in New York from Columbus, Ohio, an expanse of midtown Manhattan between Seventh and Ninth Avenues and 31st and 33rd Streets had been cleared for excavation by the New York Contracting Company. On August 20, 1905, The Washington Post reported on the progress of the excavation, calling it the “Biggest Hole Ever Dug in the Island of Manhattan.” Although Bellows left no explanation why he selected the Penn Station construction project as the subject for several large oil paintings, these works were exhibited at important art organizations and thus proved critical to his developing career. His choice of subject was certainly influenced by the aesthetic dicta of his teacher Robert Henri, who urged students to seek out scenes of modern urban life. The excavation site was within walking distance of Bellows’s studio in the Lincoln Arcade Building at Broadway and 66th Street. He may also have had a personal affinity with the subject because his father had been an architect and builder in Columbus. Given the sheer magnitude of the Penn Station project and the feats of engineering technology it entailed, there would have been no better example of modern life in New York City at that time.

The favorable reception of the first painting in the series, the bleak and bluntly realistic Pennsylvania Excavation , did much to establish Bellows’s national reputation. The second painting, Excavation at Night , was also well received. Bellows gave the third picture, Pennsylvania Station Excavation , to his friend and studio mate Edward R. Keefe; it was never exhibited during Bellows’s lifetime. Critics routinely tempered their praise for the first two paintings with reservations about what they perceived as the artist’s excessive realism. When Pennsylvania Excavation was exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1908, Albert Sterner of The New York Times characterized it as “a realistic presentation of the big hole in winter with its bedraggled snow and slush and mud” whose “power and directness of treatment verges on unbridled, brutal crudity that is ‘perfectly stunning’ no doubt, but hardly satisfying artistically." When Excavation at Night was exhibited at the New York Academy in 1909, James Huneker commented on its “grim ugliness” and doubted that Bellows would “win the favor of the crowd” because he was “uncompromising in his presentation of hard facts . . . and his candor compels him to present a pit full of steam drills and workmen, harshly lighted by electric rays, as he sees them.” Despite such negative comments about these two paintings, their originality, expressive power, and flawless bravura technique impressed the art cognoscenti and, second only to his boxing subjects, contributed to Bellows’s prestige as an artist.

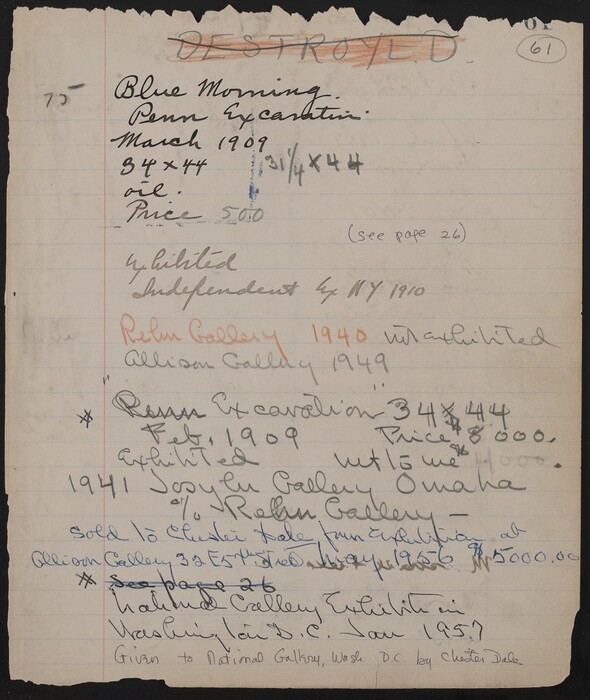

Executed in March 1909, Blue Morning was the fourth and final painting in the series . Bellows seems to have taken his critics’ reviews to heart, because it is by far the most aesthetic and impressionistic of the group, devoid of “brutal crudity” and “grim ugliness.” The picture takes its title from the bright, bluish light that pervades the scene, and is painted in Bellows’s characteristic fluid, painterly technique. Unlike the other three pictures, it does not focus on the unedifying sight of the huge excavation pit, but rather the construction workers going about their business in the foreground. Marianne Doezema has demonstrated that the highly contrived view was a combination of factual observation and fantasy: “Bellows fabricated an ideal vantage point on the far side of Ninth Avenue at the center of the excavation. The scene depicted in Blue Morning would have been viewed from a point in midair.” Both the composition and lighting effects are complex. An elevated train track runs flush across the entire top margin, and a vertical I beam extends vertically down the right side. These framing devices compress and flatten space and heighten the abstract qualities of Bellows’s design. The scene is dramatically backlit so that the figures are silhouetted against the hazy background, where the back of McKim, Mead, & White’s partially completed terminal building rises out of the indistinct pit, looking much as it did in a contemporary photograph . When Blue Morning was shown at the Exhibition of Independent Artists in April 1910, shortly before Penn Station opened in September, it was barely mentioned in the reviews. Frank Jewett Mather described it in passing as a “remarkable architectural composition.”

In December 1909, Bellows returned to the theme of urban transformation and progress in New York with The Lone Tenement and The Bridge, Blackwell’s Island (Toledo Museum of Art), both similarly atmospheric paintings that allude to another major improvement in the city’s transportation system: the newly erected Queensborough Bridge. The bridge still stands, but despite public outcry Pennsylvania Station was demolished in 1963, its grandiose statuary dispersed to other sites, to make way for Madison Square Garden. Sadly, Blue Morning, along with Bellows’s three other Penn Station paintings, are among the few remaining mementos of what was once one of the greatest edifices of New York City’s Gilded Age.

Technical Summary

The plain, heavily woven fabric support was lined with wax and remounted on a new stretcher during treatment in 1970. The original canvas was prepared with a gray ground that is presumed to have been applied by the artist, but the absence of tacking margins makes this difficult to confirm. The paint was applied rapidly in thick layers, working in every passage virtually simultaneously. There is a good deal of impasto and visible brushwork, especially in the foreground. X-radiography and infrared reflectography were used to investigate the possible existence of an underlying painting, which is suggested by brushwork visible in raking light that does not correspond to the main painting. Examination with these techniques did not add any evidence to this theory. At the time of the 1970 treatment, it was discovered that approximately 2 3/4 inches of the original painting had been folded over the reverse of the top stretcher bar, thus reducing the painting’s dimensions. Evidence suggests that this was done well after Bellows’s death, perhaps in preparation for the 1949 or 1956 exhibition at H. V. Allison Gallery. Gordon Allison recollected that Blue Morning had been reframed prior to one of those exhibitions, and was “quite certain that the upper part was purposely covered by the rabbet so as to diminish the dark effect at the top." The painting was returned to its original dimensions in 1987. At that time, the painting was strip lined along the top edge, it was stretched onto a newly fabricated stretcher, the old varnish was removed, losses (particularly at the top edge that had been folded over) were filled and inpainted, and a synthetic varnish was applied.

Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts, Gift of Mary Gordon Roberts, Class of 1960, in Honor of the 50th Reunion of Her Class

Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts, Gift of Mary Gordon Roberts, Class of 1960, in Honor of the 50th Reunion of Her Class

Crystal Bridges Museum of Art

Crystal Bridges Museum of Art

Brooklyn Musuem of Art, A. Augustus Healy Fund

Brooklyn Musuem of Art, A. Augustus Healy Fund

The Ohio State University Libraries’ Rare Books and Manuscripts Library and the Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio

The Ohio State University Libraries’ Rare Books and Manuscripts Library and the Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio

Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York

Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York