American Paintings, 1900–1945: Forty-two Kids, 1907

Publication History

Published online

Entry

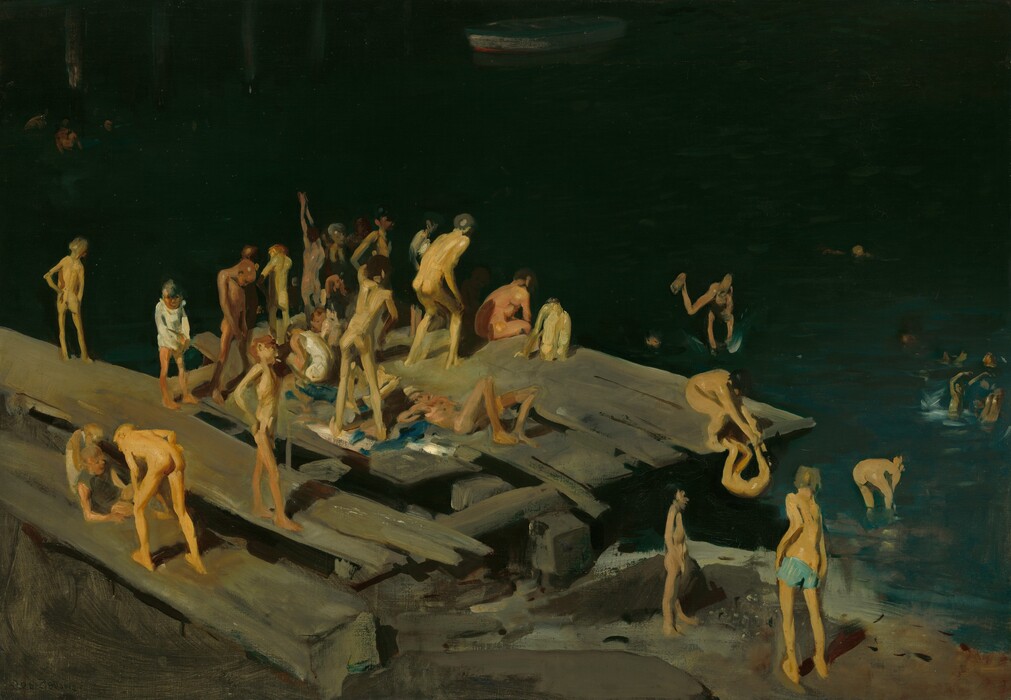

Forty-two Kids was painted in August 1907 , less than three years after George Wesley Bellows had left his home state of Ohio at the age of 22 to study art in New York City. He enrolled at the New York School of Art under Robert Henri, the artist and influential teacher around whom congregated the so-called Ashcan school of urban realists. Bellows fully subscribed to his mentor’s credo, creating work “full of vitality and the actual life of the time.” Forty-two Kids exemplifies Bellows’s early work, much of which depicts metropolitan anecdotes, including the illegal boxing matches for which he would become best known.

In Forty-two Kids, nude and partially clothed boys engage in a variety of antics—swimming, diving, sunbathing, smoking, and possibly urinating—on and near a dilapidated wharf jutting out over New York City’s East River . The wharf is painted with broad, fluid strokes from a heavily laden paintbrush, and the “little scrawny-legged kids in their naively indecent movements” are sketched with Bellows’s characteristic vigor and economy of means. The vague grid formed by the wharf’s rough-hewn planks provides a stable compositional platform for the jumble of “spindle-shanked little waifs” distributed seemingly at random across the foreground and middle ground of the canvas.

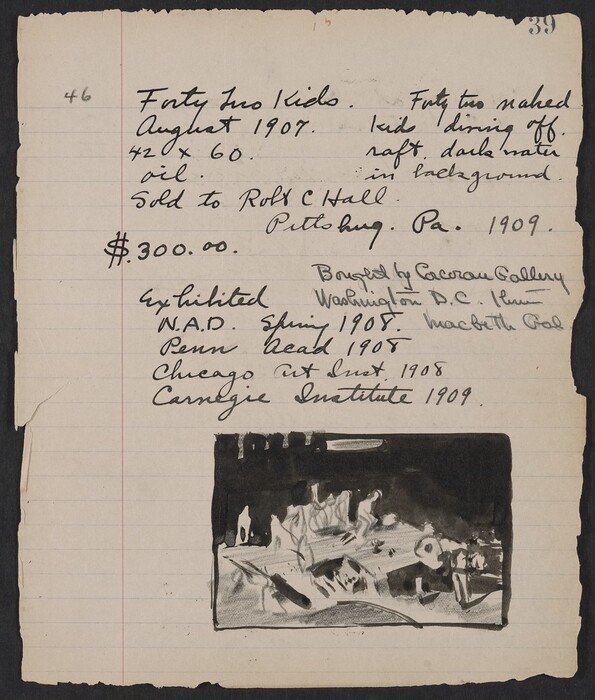

Forty-two Kids elicited significant attention when it was first exhibited. It was recognized as “one of the most original and vivacious canvases” at the National Academy of Design’s 1908 exhibition, where Bellows won the second-place Julius Hallgarten Prize for another painting, North River (1908, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia). This was only the second year Bellows had submitted to the academy. It was an auspicious sign; in April 1909, the organization inducted Bellows as one of the youngest academicians in its history.

Although it was viewed with “a pleasurable sensation” and relished for its “humor” and “humanity,” Forty-two Kids did not receive universally positive reviews. One critic condemned it for “the most inexcusable errors in drawing and general proportions,” while another denounced it as “a tour de force in absurdity.” It had been controversially denied the prestigious Lippincott Prize at the Pennsylvania Academy’s 1908 annual exhibition owing to the jury’s fear that the donor might be offended by the title and subject of the painting.

Bellows was aware of this incident. He wanted Robert C. Hall, who purchased Forty-two Kids from the Thirteenth Annual Exhibition of the Carnegie Institute in 1909, to know that “the management, feeling that Mr. Lippincott would not like the decision, would not allow the award.” When asked if he thought the jury feared Lippincott would object to the naked children, Bellows deflected attention by quipping: “No, it was the naked painting that they feared.” He did not elaborate, leaving unclear whether he meant the painting’s sketchy appearance or its lowly subject.

Although Bellows’s painting appears innocent enough to viewers today, the mixed reception likely stemmed from the connotations of what one critic called the “curiously freakish subject.” Even as Bellows’s scene recalls Thomas Eakins’s 1885 painting Swimming , it also echoes the lowbrow style and content of comic strips like Hogan’s Alley, which chronicled the capers of its slum-dwelling protagonist, the Yellow Kid. Where Eakins evokes a tradition of Arcadian naturalism, aligning his nude, sun-dappled subjects with classical antiquity, Bellows’s undeniably modern kids are accorded no such nobility. Around 1900, the slang term “kid” connoted young hooligans with predilections for mischief and petty crime; its lower-class associations would have been clear to Bellows’s audience. Bellows had used colloquial titles before, in his 1906 paintings Kids (now in the collection of James W. and Frances G. McGlothlin) and River Rats (private collection, Washington, DC). The latter employs an epithet for juvenile delinquents that draws on an established rhetorical link between immigrants and animals. This association was also applied to the kids in the Gallery’s picture, who were described as “simian.” This was likely a reference to the then-popular caricature of Irish Americans as apelike, although the varied skin tones of Bellows’s kids appear to reflect the range of ethnicities—Italian, Russian, German, Polish, and Irish—represented in the poor neighborhoods of Manhattan’s East Side.

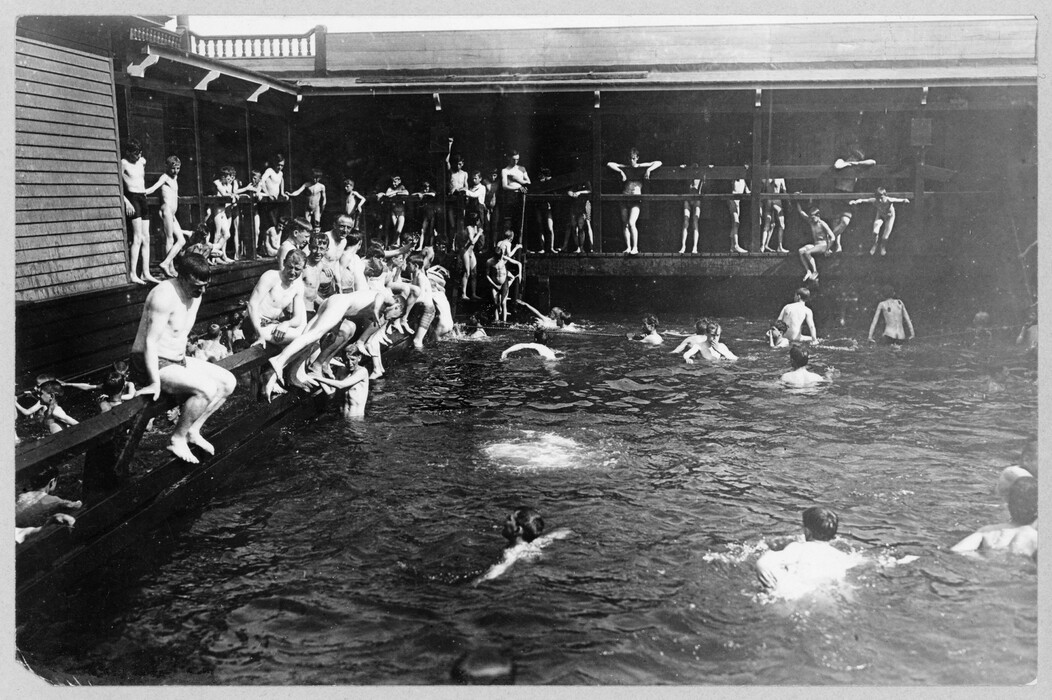

The “simian” slur was surpassed by another critic, who declared: “most of the boys look more like maggots than like humans.” Another simultaneously likened Bellows’s kids to insects and germs when he suggested that “the tangle of bodies and spidery limbs” was akin to “the antics of magnified animalculae.” Even Bellows’s widow, Emma, used entomological vocabulary when she recalled the “old dock” north of the Fifty-Ninth Street Bridge, from which her husband might have made preparatory sketches for Forty-two Kids, describing the area as a “dead end neighborhood—swarming with growing boys.”

Contemporaneous literary descriptions of New York City’s tenements relied on metaphors that linked recently arrived immigrant slum dwellers and their dirty environments with all manner of unhygienic animals. The colorful similes applied to Forty-two Kids can be understood in this context. From 1890 until the mid-1920s, some 25 million immigrants entered the United States. With the Immigration Act of 1891, the federal government established rigorous medical screening that, among other things, barred persons suffering from contagious diseases. Foreigners, in general, came to be judged as diseased and contagious. Bathing, in municipal swimming pools and open-water floating baths, was endorsed as a healthy and hygienic form of exercise, a way of cleaning, quite literally, recently arrived immigrants. Bellows’s swimming hole, however, is far from salubrious. As one critic noted, the painting has “a bituminous look ill assorted with the idea of bathing.” Although Bellows reportedly said, “One can only paint what one sees,” Forty-two Kids elicited responses that went beyond the painting’s superficial and purely visible subject and drew on the distasteful metaphors with which the city’s immigrant populations were associated. Described as bacteria, maggots, and insects, Bellows’s kids were characterized as vectors of contagion, an affiliation quite in keeping with the widely held belief, at the beginning of the 20th century, that unrestricted immigration posed a very real threat to individual Americans’ well-being and the nation’s social health.

Technical Summary

The painting is executed on a medium-weight, plain-weave canvas that was primed with a thin grayish-white ground that was commercially applied, evidenced by its presence on the still-intact tacking margins. The painting is lined with a plain-weave canvas using aqueous adhesive, and is stretched onto a nonoriginal keyable stretcher. The paint was applied very freely and spontaneously. In some places, especially in the lower part of the design, the paint is thin enough that the light ground color is visible and the texture of the fabric remains prominent. In other areas, however, the paint was applied more thickly, often with substantial brushmarks and points and ridges of impasto. The great majority of the paint was applied wet into wet and shows signs of blending and smearing of one color into another. In many places, the artist used a sizeable brush to define the larger design elements, such as the boards of the dock, with a few bold strokes. The paint that describes the deep blackish water in the background was slow-drying and quite liquid. Drip marks in this area are evident in the upper right, indicating that the painting was turned on its side and the black paint continued to flow. In many figures, the artist used a small, stiff, flat brush to produce his characteristic streaky, blended strokes of paint that define the boys' bodies with a great economy of means. Many random bumps of paint are visible throughout the surface, indicating that the artist scraped up dried paint from his palette and allowed it to become incorporated into his colors. The paint layer is in good condition, with only a few small inpainted paint losses scattered throughout, some areas of mild abrasion in the lower third of the painting, and some areas of prominent drying cracks. The edges are also heavily retouched. Corcoran conservation records show a number of treatments throughout the past century, and indicate that the varnish layer is complicated by the addition of a thin wax layer, followed by two successive synthetic resin coatings applied many years apart.

The Ohio State University Libraries’ Rare Books and Manuscripts Library and the Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio

The Ohio State University Libraries’ Rare Books and Manuscripts Library and the Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio

George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Amon Carter Museum of Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Amon Carter Museum of Art, Fort Worth, Texas