American Paintings, 1900–1945: Haying, 1939

Publication History

Published online

Entry

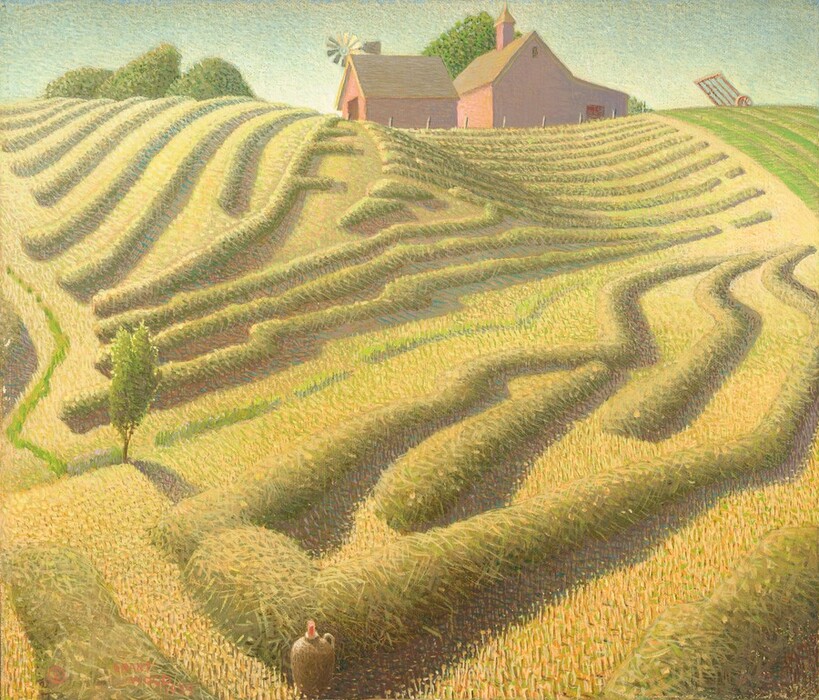

Grant Wood’s early biographer Darrell Garwood identified Haying and New Road as “a set of twin landscapes” that the artist painted during the unusually short period of three weeks in June 1939, shortly after recovering from a minor operation. They were painted specifically to be exhibited at a fine arts festival at the University of Iowa in Cedar Rapids. Wood had been engrossed with lithography for the previous three years, and these were the first oil paintings he had executed since Spring Turning (1936, Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC). Shortly after completing them he painted the well-known Parson Weems' Fable (1939, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, TX), and he continued to work regularly in oil until his death in 1942.

Although Haying and New Road were inspired by views Wood saw during his travels between Iowa City and Lake Macbride, they are representative examples of the idealized landscapes of rural Iowa that Wood first painted in Stone City, Iowa . Wood’s choice of subject was dictated in part by his rejection of the urban Northeast’s cultural hegemony over the rest of the United States and his belief that an artist has a special rapport with his native area. In his 1935 essay Revolt Against the City Wood expresses his annoyance at the eastern habit of stereotyping the Midwest as “provincial” and populated by “peasants.” He declares that Iowa, his native state, is “a various, rich land abounding in painting material.” In accordance with Wood’s statement that “central and dominant in our Midwestern scene is the farmer,” his landscapes feature the cultivated lands, farms, manual farm machinery, windmills, and grazing animals characteristic of Iowa. The few previous scholarly discussions of Haying and New Road have generally centered on the barn, a staple of the regionalist landscape, as a rapidly vanishing icon of the American countryside that signified community and social stability.

Despite Wood’s regionalist convictions and advocacy of American subjects and artistic styles, European influences are discernable in his mature oeuvre. Wood was familiar with the contemporary Neue Sachlichkeit painters in Germany, who practiced various forms of detailed realism and whose work he had seen during his 1928 trip to Munich. The wide-angle vista, bird's-eye view, slightly distorted linear perspective, lack of atmospheric perspective, unusually high horizon line, and meticulous attention to detail in many of Wood’s landscapes also reflect his keen awareness of 15th-century northern European precedents. Operating in tandem with Wood’s evocations of the traditional harvesting scenes found in the calendar pages of illuminated manuscripts and paintings such as Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Hay Making (1565, National Gallery, Prague), the eerie absence of anecdotal human activity in Haying reveals his modernist sensibilities.

Although Wood has generally been considered a conservative realist, his habit of reducing landscapes into a series of simplified, ornamental, abstract, repeating patterns demonstrates a familiarity with modernism and art deco design. Brady M. Roberts has recently noted that Haying’s complex structure of multicolored, thin, horizontal brush strokes creates “a surface vocabulary approximating Seurat’s pointillism.” Although Haying and New Road were executed in Wood’s precise, crosshatched technique, the relatively loose handling of paint has more in common with his plein-air studies than the smoother, more polished surfaces of his major paintings. In a letter to the offices of Associated American Artists in New York Wood referred to them as “sketches,” and it is possible, as the typewritten papers attached to their reverses suggest, that he planned to paint larger versions.

Wood characterized the verdant Iowa landscape as an idyllic land of plenty and gave no indication in his paintings of the severe economic problems and natural disasters that beset Iowa farmers during the 1930s. Haying betrays no evidence of severe soil depletion and erosion, declining crop prices, the problems engendered by tenant farming, the fact that many farm owners were overburdened with heavy mortgages and threatened with foreclosure, manifestations of labor unrest among the farmers, the mass exodus of Iowans to other states, and the many farmers who abandoned their agricultural lifestyle and sought a better livelihood in growing urban industrial centers. While Wood acknowledged that the farmer's life “is engaged in a constant conflict with natural forces,” he, unlike John Steuart Curry and lesser-known Texas regionalists such as Jerry Bywaters and Alexandre Hogue, did not stress the ravages of natural calamities in his benign, sunny landscapes. Although many of Iowa's problems were successfully addressed by state and federally funded programs, the idealistic agrarianism of landscapes such as Haying was far removed from reality.

James Dennis has explained this phenomenon by citing Wood’s populist belief that the farmer was a virtuous, pure, and self-sufficient tiller of the soil who was immune from corrupting influences. This idealized view of rural life had its origins in the late 19th century. During the 1930s, isolationist, nationalist agrarians revived this attitude in response to the growing encroachment of urbanization into the American heartland. Dennis discusses how Wood reinforces this myth by excluding mechanized farm machinery in his agricultural landscapes, as well as railroads, utility poles, telephone wires, billboards, and other signs of the modern industrial era. Here the haying machine on the horizon signifies the farmer’s close, physical relationship with the soil through manual labor. Nevertheless, Wood revealed his involuntary susceptibility to technology by illustrating wide expanses of uniformly cultivated land that could only have been accomplished through mechanization. Similarly, Wood’s characteristic form of abstraction was influenced by innovations in industrial design, such as streamlining.

Despite their disarmingly benign and seemingly straightforward appearance, landscapes such as Haying and New Road are complex, carefully orchestrated works full of ambiguities and inconsistencies that reveal much about Wood’s unique brand of regionalism. If New Road depicts the country in 1939 as literally and figuratively approaching a crossroads, a fateful turning point between the calamities of the Great Depression and what would prove to be the even more ominous, existential challenges of World War II, the irregular patterning of the fields in Haying presents the same moment as even more intricate and mazelike. The corked water jug resting in the shadows at the elbow of an L-shaped row in the foreground beckons the viewer to begin their journey through the painting’s labyrinth of hay. Like a traveler at a crossroads, a decision must be made to go to the right or to the left.

Technical Summary

The support consists of a medium-weight, plain-weave, double-threaded fabric that was adhered to a secondary support of pressed board, which was in turn mounted to a Masonite panel. These materials were probably laminated prior to painting, as some paint has spilled over the edges onto the sides of the board. An original typed label attached to the reverse reflects Wood’s concern about protecting his rights and retaining monetary value of his works after they were sold: “THIS PAINTING IS SOLD WITH THE UNDERSTANDING THAT I RESERVE THE RIGHT TO MAKE A LARGER PAINTING OF THE SAME SCENE IF I SO DESIRE. GRANT WOOD.” The fabric texture is visible through the thin white ground layer. Paint (estimated to be oil but may also be tempera or a tempera mixture) was mostly built up in thinly applied opaque to transparent fine hatching strokes and dabs. At some point glass was placed directly on the paint surface, resulting in minor losses when the glass was removed. There are also flattened areas of paint scattered across the paint surface from its contact with the glass. Infrared examination of the painting showed underdrawing around the roof of the barn and changes to the hay wagon and to the field. There is no surface coating. The original light wood frame was probably made by Wood or an assistant.

Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha. Gift of the Art Institute of Omaha, 1930.35

Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha. Gift of the Art Institute of Omaha, 1930.35