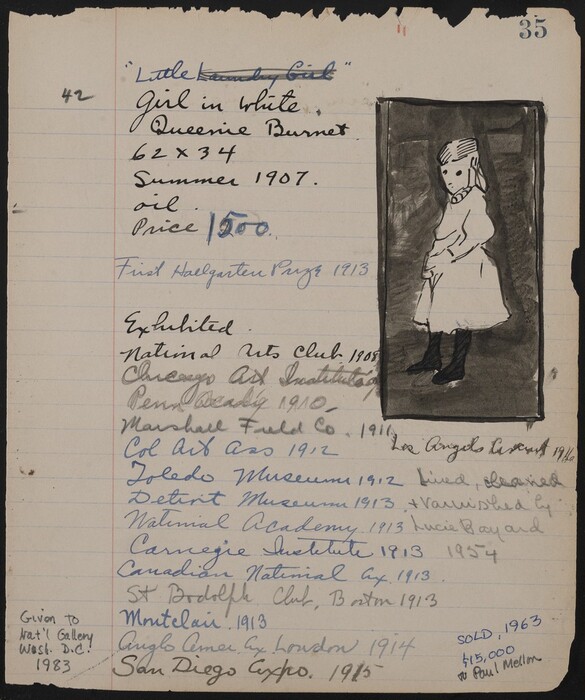

American Paintings, 1900–1945: Little Girl in White (Queenie Burnett), 1907

Publication History

Published online

Entry

In this sympathetic image, the artist has represented the demure laundry girl Queenie Burnett attired in a simple white dress and black stockings, posing with her hands folded before her, set against a dark brown background. Queenie’s difficult life as a child laborer is manifested in her gaunt face, exaggeratedly large eyes, unkempt hair falling over her shoulders, and her awkward figure. Bellows has also managed to capture his subject’s uneasiness at finding herself in an artist’s studio posing for her portrait.

Originally titled Little Laundry Girl , this portrait of a figure in a white dress is reminiscent of James McNeill Whistler’s The White Girl (Symphony in White, No. 1), the full-length portrait that had inspired such diverse images as William Merritt Chase's fashionable society portrait Girl in White (c. 1898–1901, Akron Art Museum, OH) and Robert Henri's slightly tawdry Young Woman in White. In painting the young, working-class girl who delivered his laundry, Bellows, like Whistler, was flaunting the conventions of grand-manner portraiture traditionally reserved for the social elite. He was also following the advice of his friend and teacher Robert Henri, who admonished Bellows to select subjects that reflected the realism of modern urban life. Fulfilling that goal, he portrayed the recreational activities of New York City’s lower-class children in such paintings as River Rats (1906, private collection) and Forty-Two Kids. In 1907, he began to explore the street-urchin genre popularized in the United States during the last quarter of the 19th century by Frank Duveneck and especially John George Brown. Bellows painted two full-length portraits of individual children, Little Girl in White and Frankie the Organ Boy (both 1907, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO), and the following year he executed the three-quarter length Paddy Flannigan (Erving and Joyce Wolf Collection). Like the other artists in Henri’s circle, Bellows eschewed the traditional idealizing approach with his youthful subjects, instead portraying them in a bluntly realistic manner.

The painting’s unusual mix of aestheticism and realism is simultaneously appealing and unsettling. A newspaper reporter who visited Bellows’s studio in 1908 may have had Little Girl in White in mind when he commented on portraits of “street gamins.” He noted that although they were “brimming with humor,” the images possessed a plaintive quality “which brings tears and sends people to rescue work.” However, the blunt realism of Bellows’s early works often provoked critics. A reviewer for the New York Evening Mail criticized it as a “flat failure, looking as if it were cut out of wooden blocks.” Despite the portrait’s mixed critical reception, it was immensely popular with the general public. Little Girl in White is noteworthy as the first of Bellows’s figural works to be widely exhibited throughout the country. He was awarded the first Hallgarten Prize of $300, reserved for artists under the age of 35, when the painting was shown at the National Academy of Design in 1913.

Technical Summary

The medium-weight, loosely woven fabric support was at some point lined with a wax/resin adhesive and remounted on a nonoriginal stretcher. Bellows apparently altered the size of the composition at least twice, because the background paint layers extend into the side and bottom tacking margins and there is a set of old tacking holes and a horizontal edge of thickly applied original paint below the top edge. Infrared examination reveals sketchy background details (a higher upper edge of the floor and a vertical architectural element to the right) that are not visible to the naked eye. The artist applied paint vigorously, with highly textured and unblended brushstrokes in the white dress progressing to a much smoother application in the dark areas and background. There are small, scattered paint losses in the middle of the painting, and ultraviolet examination reveals older losses that have been overpainted. In a recent treatment of the painting (2005–2011), in which the old varnish and most of the overpainting was removed, the extent of these losses was revealed. The losses in white dress are rather extensive in the center; they consist of an old, branched tear and numerous little gouges in the canvas that occurred long ago during an effort to scrape off an old patch adhered to the reverse with white lead. Severe abrasion of the background, particularly in the brown areas just to the left of the figure, was also revealed when the overpaint was removed. A newer tear is found in the upper left. Also during this treatment, the wax lining was removed and replaced with a polyester fabric adhered with synthetic adhesive. A new surface coating of synthetic resin was applied after new inpainting of the losses was applied. When the lining was removed, an inscription was revealed on the reverse.

The Ohio State University Libraries’ Rare Books and Manuscripts Library and the Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio

The Ohio State University Libraries’ Rare Books and Manuscripts Library and the Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio