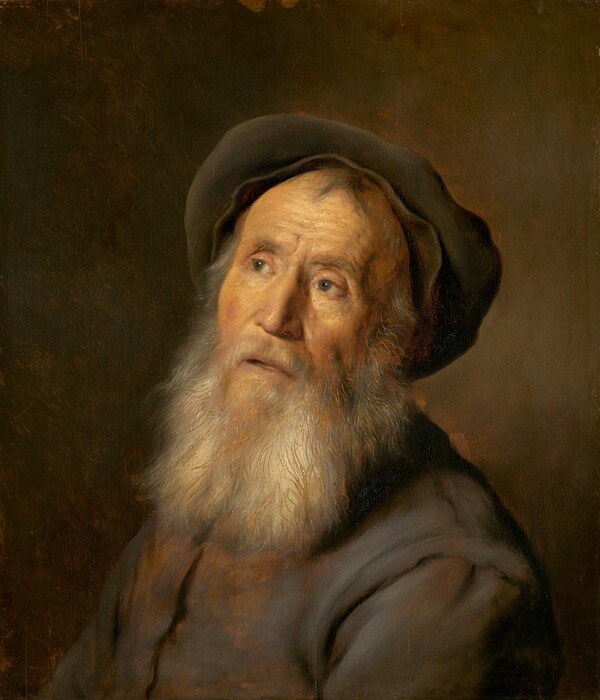

Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century: Bearded Man with a Beret, c. 1630

Publication History

Published online

Entry

This old man’s aged face, with its irregular features, is alive with emotion as he gazes upward toward the left, his mouth partially open. Light caresses his face, articulating the wrinkled skin of his furrowed brow and glinting off his eyes. Rhythmic strands of hair from his full, flowing beard and moustache further enliven the image. Lievens painted this memorable work in Leiden, at a time when he and Rembrandt van Rijn were establishing themselves as two of the finest young artists in the Netherlands. They shared an interest in the depiction of tronies, or head and shoulder studies of young and old individuals. Tronies were character studies rather than portraits of specific people, and these two artists painted them to evoke a wide range of human emotions. Sometimes these works served as models for larger-scale paintings, but more often they seem to have been created, and valued, as independent works of art.

Lievens painted, drew, and etched numerous tronies during the late 1620s and early 1630s. He was particularly gifted in this type of work and knew how to exploit his painting techniques to enhance the animated character of a sitter’s appearance. As in this instance, he indicated the transparency of the elderly man’s skin with thin

A contemporary observer would have seen the beret as an outmoded hat style, found primarily in scholarly dress. The beret thus would have enhanced the “thoughtful” disposition of the man’s expression—the mien of someone who reflects on the world he sees around him. Both Lievens and Rembrandt found that with age came a remarkable sense of character, not only through the creases that line a wizened face, but also in the inner wisdom of one who has experienced the vagaries of life.

Lievens’ tronies were highly regarded by his contemporaries. In his autobiographical account of 1629–1631, Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687) wrote that “in painting the human countenance [Lievens] wreaks miracles.” Huygens also noted that a number of prominent collectors had already acquired examples of such head studies (“works of inestimable value and unrivaled artistry”), including the stadtholder, Prince Frederik Hendrik; his treasurer, Thomas Brouart; the artist Gheyn III, Jacques de; and the Amsterdam tax collector Nicolaas Sohier. Unfortunately, the name of the collector who was the first owner of this remarkable image is not known.

Technical Summary

The painting was executed on an oak[1] panel composed of two vertically grained planks. The planks vary in thickness slightly, and the reverse of the panel is beveled. There are two very thin ground layers: a red one on top of a white one.[2] Infrared reflectography at 1.5 to 1.8 microns[3] and examination with a stereomicroscope revealed that the artist had laid in the basic composition with a brushy sketch in fluid brown paint. The sketch was allowed to show through the paint in places. The final image was executed with rich paint that was blended and smudged using both brushes and fingers. The paint in the sitter’s face was applied wet-into-wet with some impasto in the highlights. The artist dragged the back end of his brush through the wet paint and in some places even the ground to create the highlights in the sitter’s hair, beard, and eyebrows. Artist’s changes are visible in the contours of the figure and at the junction of his hair and face.

The painting is in very good condition. A fine craquelure pattern can be seen in the brown sketch paint. The varnish is slightly uneven in gloss. No conservation treatment has been undertaken since its acquisition.

[1] The characterization of the wood as oak is based on visual observation only.

[2] The two ground layers were confirmed by cross-sections taken by the NGA Scientific Research department (see report dated March 20, 2007, in NGA Conservation department files).

[3] Infrared reflectography was performed using a Santa Barbara Focalplane InSb camera fitted with an H astronomy filter.