Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century: Cathedral of Saint John at 's-Hertogenbosch, 1646

Publication History

Published online

Entry

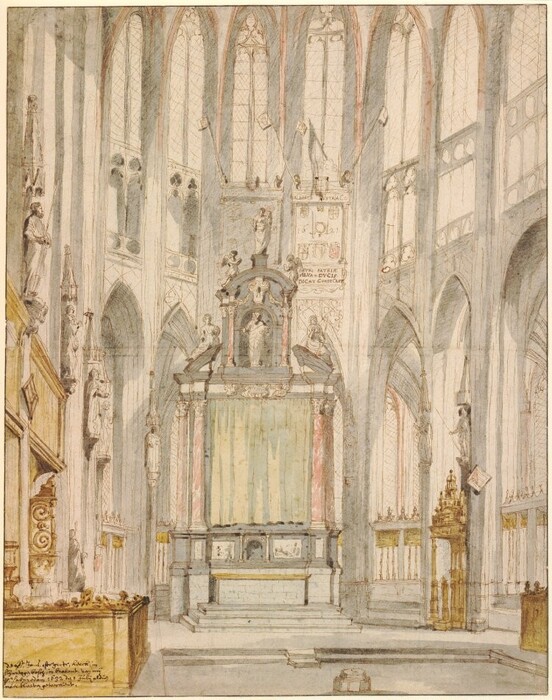

In this depiction of the Sint Janskathedraal (Cathedral of Saint John), one of Saenredam’s grandest paintings, the artist has brought the viewer into the apse of this great cathedral to experience the full majesty of the soaring architecture towering above. He achieved this sensation in many ways: through careful compositional arrangement that reinforced the dynamic character of the architecture; through subtle use of linear and atmospheric perspective that helped open the space and fill it with light and air; and, finally, through his choice of a vertically proportioned, large panel that allowed him to paint on a scale suitable for such an imposing setting.

The Sint Janskathedraal is the largest Gothic cathedral in the Netherlands. When Saenredam painted this image in 1646 he conceived it in such a way as to include the full scope of the late-fifteenth-century choir. From this low vantage point just inside the crossing, the pilasters that rise without interruption from their bases to the light-filled, vaulted ceiling give the space a dynamic, vertical thrust. As the central ribs of the pilasters arch out to form the ribs that support the vault, their color changes from light ocher to delicate pink. Saenredam has placed the keystone of the vault at the very top of the painting in a way that pulls together the richly ornate architectural elements. Despite the apparent reality of the scene, however, the relationship of this image to the actual site is quite complicated. Saenredam has shifted certain forms for compositional reasons. The two arches in the arcade on the right, for example, are rounded rather than pointed, an adjustment undoubtedly made because pointed arches would have appeared quite distorted in this perspectival arrangement. He has also lowered the position of the central window of the clerestory to emphasize the central axis of the apse. One other change, the introduction of the Adoration of the Shepherds, 1612, by Bloemaert, Abraham, into the high altar, was made for different reasons, ones that relate to the complex issues surrounding the creation of this work that are discussed below.

The origins of the story actually predate the execution of the painting by seventeen years and are intimately connected with one of the most important military exploits during the reign of Prince Frederik Hendrik: the siege of ’s-Hertogenbosch in 1629. With the capitulation of the city to the forces of the States General on September 14 of that year, Frederik Hendrik had achieved his greatest victory in the long struggle against the Spanish forces of the southern Netherlands. Efforts were immediately made to cleanse this Catholic stronghold of papist influence. Catholic services were forbidden in the city, priests were forced to leave, and the churches were confiscated. Indeed, two days after he had entered ’s-Hertogenbosch, Frederik Hendrik, along with his wife, Amalia van Solms, attended a Reformed Church service in Sint Janskathedraal.

As part of the articles of capitulation, the northern forces did not hinder the clergy from taking with them objects from the churches. The bishop of ’s-Hertogenbosch, Michael Ophove (Ophovius), recorded in his diary how the clergy removed most of the precious objects from the treasury, which were packed and transported in carts, provided, interestingly enough, by the Prince of Orange. Among the sculptures taken for safekeeping was the miracle image of Onze Lieve Vrouw van Den Bosch (Our Virgin Mary of Den Bosch), the most sacred icon in the church, one that had made Sint Janskathedraal a mecca for pilgrims since the fourteenth century. Even the large altarpiece, Bloemaert’s God with Christ and The Virgin as Intercessors, 1615, was removed from the high altar and transported to the southern Netherlands.

Given the political situation, it seems unlikely that Saenredam had ever traveled to ’s-Hertogenbosch prior to Frederik Hendrik’s successful siege in 1629, thus he never would have actually visited the cathedral when it was a Catholic shrine. When he did arrive at the end of June 1632, not all remnants of the Catholic past had been removed from the cathedral; the apse, however, obscured from the sight of worshipers by an enormous choir screen, was no longer used for services. As is evident from Saenredam’s drawing of the high altar, which is dated July 1, 1632, the altar lay abandoned, stripped of all its liturgical objects . A large green curtain covered the void left by the removal of Bloemaert’s altarpiece.

Although there is little doubt that this drawing served as a preliminary study for the painting, which is dated fourteen years later in 1646, it is remarkable that Saenredam has reconstituted the interior as though it were still a Catholic cathedral. Candles and flowers have been returned to the altar, and a small gilt crucifix occupies the altar niche. Saenredam has filled the high altar not with a curtain but with Bloemaert’s The Adoration of the Shepherds , a painting he would have seen in ’s-Hertogenbosch in the Convent of the Poor Clares. Behind the sculptural elements at the top of the altar, depicting the Virgin and Child with two adoring angels, hang two large plaques surmounted by flags. The one on the right is dedicated to Philip II of Spain, and the one on the left to his daughter, the Infanta Isabella, regentess of the southern Netherlands. Although no clergy or parishioners are depicted, the polychrome sculpture of the kneeling Bishop Masius, to the left of the altar, adds a note of reverence to the scene. That Saenredam sought to create this effect through the sculpture is evident not only in the way he emphasized the startlingly realistic appearance of the figure, but also through the private space he created for Masius by choosing a low vantage point near the choir stall.

Saenredam’s extraordinary painting, made so long after his visit to ’s-Hertogenbosch, is remarkable in a number of ways. To begin with, it is difficult to see how the artist managed to convey the architectural details of the church so accurately on the basis of his drawing of the high altar. Although Saenredam often painted scenes long after he had made his preliminary studies, his painting of the choir of Sint Janskathedraal includes more of the church than does his drawing. Perhaps a construction drawing once existed that he used as his model. His working procedure often included such studies, and examination of the painting with infrared reflectography at 1.5 to 1.8 microns reveals an extensive underdrawing similar to his carefully proportioned and ruled working drawings. The painting follows the underdrawing almost exactly, with one important exception: Saenredam elongated the proportions of the apse in his final composition. In the underdrawing the ribs join the keystone slightly below rather than at the top edge of the painting .

Particularly remarkable for a painting of 1646 is its emphasis on the Catholicism of the cathedral and the attention drawn to both Philip II of Spain and the Infanta Isabella. The only conclusion that can be drawn is that Saenredam was deliberately trying to re-create the character of Sint Janskathedraal as it looked before the overthrow of Spanish authority in ’s-Hertogenbosch, that is, prior to the events of 1629. Just why he did that is not at all clear, but the large scale of the panel indicates that the painting was commissioned. To try to understand who might have commissioned this Catholic representation of Sint Janskathedraal and why Saenredam painted it in 1646, one has to return to 1632 and examine the circumstances surrounding Saenredam’s visit to ’s-Hertogenbosch.

It has been suggested that Saenredam went to ’s-Hertogenbosch to visit Jan Pietersz de Jonge (Johannes Junius), the son of the artist’s childhood guardian and a Calvinist preacher who had been sent from his native Assendelft to help steer the local populace away from the Catholic religion. It seems probable, however, that he had a different reason for making this trip. Junius was at that time the preacher in another of the local churches, Sint Pieterskerk, which Saenredam also depicted during his visit that summer. His work at Sint Pieterskerk did not begin until he had finished his campaign at Sint Janskathedraal, hence it is likely that the visit was primarily to examine the cathedral and only secondarily to visit Junius. Moreover, Saenredam’s painting of the Choir of the Sint Pieterskerk (private collection), which he executed in 1632, also emphasizes the Catholic heritage of the church rather than its then-Protestant character, a surprising focus given the emphasis of Junius’ ministry.

One can thus assume that Saenredam came to ’s-Hertogenbosch for the purpose of painting Sint Janskathedraal. This hypothesis is backed up by a surprising discovery from dendrochronological examination of the panel Saenredam used for his painting. The tree from which the panel was made was cut down around 1630. It thus seems probable that Saenredam ordered this large and unusually shaped panel at the time of his visit to ’s-Hertogenbosch in 1632 rather than in the mid-1640s. This bit of technical evidence reinforces the sense that a Catholic patron must have induced Saenredam to make the trip, a supposition further strengthened by the nature of the drawings he made of the interior of the cathedral.

Saenredam’s drawing of the high altar was but one of four imposing drawings he made of the interior of Sint Janskathedraal between June 30 and July 3, 1632. Chronologically, the first of these drawings was of the Tomb of Bishop Gisbertus Masius , the tomb of the energetic bishop of ’s-Hertogenbosch that is visible to the left of the altar in the painting. Masius was an important figure in that city in the first decades of the seventeenth century, responsible for instilling the strong Jesuit presence there. Under the patronage of the Archduke Albert and the Archduchess Isabella, Masius established a Jesuit college in town. After the beginning of the Twelve Year’s Truce in 1609 he began an ambitious campaign to revitalize the cathedral. In 1610 an elaborate new choir screen was commissioned for the cathedral that contained a large number of sculptures and two altars. After Masius’ death in 1614, the new bishop, Nicolaus Zoesius, oversaw the construction of Masius’ tomb, a new organ, and, most important, the high altar, which was dedicated in 1620. As Saenredam’s other two drawings of the interior of the cathedral focused on the choir screen, all four of his renderings—the high altar, Masius’ tomb, and the two of the choir screen—depicted important architectonic and sculptural elements added to the cathedral during the tenure of recent Jesuit bishops.

Although no documents exist that identify Saenredam’s patron, it may well have been a very powerful organization within the church structure known as the Illustere Lieve Vrouwe Broederschap (Illustrious Brotherhood of the Virgin Mary). This brotherhood, founded in the early fourteenth century, had begun in the sixteenth century to add a number of honorary, nonreligious members, called Zwanenbroeders (“Swan brothers,” since they were supposed to supply a swan each year for a banquet). Among them was Willem of Orange, who joined in 1566. All subsequent Princes of Orange were members ex officio, therefore Frederik Hendrik was also a member of this body. It may well be for this reason that Frederik Hendrik was so considerate of Catholic interests after his victory in 1629, at a time when the Reformed Church was doing all it could to purge ’s-Hertogenbosch of papist influence. In any event, special dispensation was given to the brotherhood, and it was the only Catholic organization in the city that was not forced to disband after the capitulation.

Before Saenredam visited ’s-Hertogenbosch he seems to have worked closely with Catholics in Haarlem who wanted to perpetuate the memory of bishops who served at the Church of Saint Bavo when it was a Catholic cathedral. Perhaps members of the brotherhood in ’s-Hertogenbosch heard of these endeavors and requested that Saenredam come work with them in a comparable fashion. Just why Saenredam did not complete the painting right away is not known, but it may well have been judged politically imprudent to do so. During the 1630s leaders of the Reformed Church objected strenuously to the existence of this Catholic organization, particularly Gijsbert Voet (Voetius), a minister in Utrecht. Many heated discussions were held, and finally a compromise was reached whereby the brotherhood could continue its existence as long as its membership was limited to thirty-six members, half Protestant and half Catholic. This issue was of such consequence that the final decision was made by the States General, in 1646, the year in which Saenredam finally executed this painting. Thus, the commission for this depiction of the Sint Janskathedraal as it had appeared when it was a Catholic cathedral seems to have come to fruition only after this important issue had been resolved.

No record of this painting has been found in seventeenth-century archives, hence it is not yet possible to trace its early provenance. Just how the painting ended up in a small provincial church in southern France before it entered the art market in 1937 suggests a fascinating story that it is hoped some day will come to light.

Technical Summary

The cradled support panel is composed of three vertically grained oak boards. Dendrochronology gives a felling date of approximately 1630 for all three boards.[1] Board widths are roughly equal at left and center and slightly narrower at right. Several checks exist at top and bottom, and gouges, some fairly deep, are found along the edges and in an intermittent horizontal band across the center.

Infrared reflectography at 1.5 to 1.8 microns[2] reveals a detailed fine-line underdrawing apparently based upon a preliminary construction drawing. Minor changes appear in the spear held by the sculpted figure at the far right, in the statue to the right of center, and in the arc of the ribs in the vault.

Paint was applied in transparent washes, glazes, and fine brushwork that leave the thin off-white ground layer and architectural underdrawing plainly visible. Scattered small losses indicate a history of flaking. Abrasion is found overall, particularly in the stone floor, the pilaster and engaged statue to the right of the altar, and the pilaster to the left of the altar. A conservation treatment was carried out in 1987–1990 to remove discolored varnish and inpainting and accurately reconstruct abraded passages.

[1] Dendrochronology was performed by Dr. Peter Klein, Universität Hamburg (see report dated January 27, 1987, in NGA Conservation department files).

[2] Infrared reflectography was performed with a Santa Barbara Focalplane array InSb camera fitted with an H filter.

Photo © Trustees of the British Museum, British Museum, London

Photo © Trustees of the British Museum, British Museum, London

Photo: RMN / Art Resource, NY. Photographer: Hervé Lewandowski, Musée du Louvre, Paris

Photo: RMN / Art Resource, NY. Photographer: Hervé Lewandowski, Musée du Louvre, Paris

Noordbrabants Museum, ’s-Hertogenbosch

Noordbrabants Museum, ’s-Hertogenbosch