Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century: The Halt at the Inn, 1645

Publication History

Published online

Entry

Isack van Ostade lived in Haarlem, yet little of his work reflects his native cityscape. Rather, he took delight in depicting life outside the city, much as a traveler passing through one of the small villages in the region would have experienced it. In this painting, the artist portrayed the bustle of activity outside a village inn as two well-dressed travelers arrive and dismount from their horses. A plainly clad woman with a child strapped to her back stands to watch while other figures converse with one of the travelers. The main street of the village is filled with other groups, among them, men smoking pipes on a bench before the inn, a child playing with its mother’s apron, and a man talking to a woman who spins yarn. Van Ostade creates a sense of conviviality by the apparent informality of these human contacts and the inclusion of an array of animals within the scene. He added to the picturesque character by emphasizing the aged brick and mortar of the inn and the vines that grow over its weathered tile roof.

This sympathetic view of village life is an outgrowth of attitudes evident in various series of landscape etchings published in Haarlem and Amsterdam in the second decade of the seventeenth century during the Twelve-Year Truce (1609–1621). Prints by Visscher, Claes Jansz, Buytewech, Willem, Velde, Esaias van de, I, and Velde, Jan van de, II depicted meandering roads on which travelers pass from one village to the next, occasionally resting before an inn, as in Jan van de Velde’s etching Ver (Spring), 1617. Title pages to these series emphasized that these views were of “pleasant places” in the vicinity of Haarlem and that they were made for the enjoyment of city viewers. Except for occasional depictions of specific inns or ruins, precise locations were of less consequence than the sense of delight one would receive traveling through the landscape and its villages.

Van Ostade began painting such “halt before an inn” scenes as early as 1643, the year he entered the Haarlem Saint Luke’s Guild. While the delight he took in depicting peasant life, already evident in paintings from the early 1640s, may have derived from the inspiration of his older brother Adriaen, this particular subject matter was his own invention. Not only did the varied activities before an inn give him an opportunity to exploit his talents as a genre painter, such scenes also suited his abilities as a landscapist. As is evident from this example, he was particularly adept at depicting landscape elements and atmospheric effects. Part of what makes this scene so vivid are the nuances of light on the buildings and figures that have filtered through the overcast sky and the suggestions of smoke that rise from the inn’s chimney.

To judge from a large number of surviving drawings, Van Ostade seems to have frequently traveled along such roads and to have carefully observed the buildings and people he encountered on his journeys. None of the motifs in the drawings, however, relate specifically to the paintings, which suggests that he used his drawings as a point of departure and freely elaborated on his observations when he came to compose his paintings. Interestingly, the buildings in the painting seem somewhat more dilapidated than those he drew, which indicates that he purposely sought to create this picturesque effect.

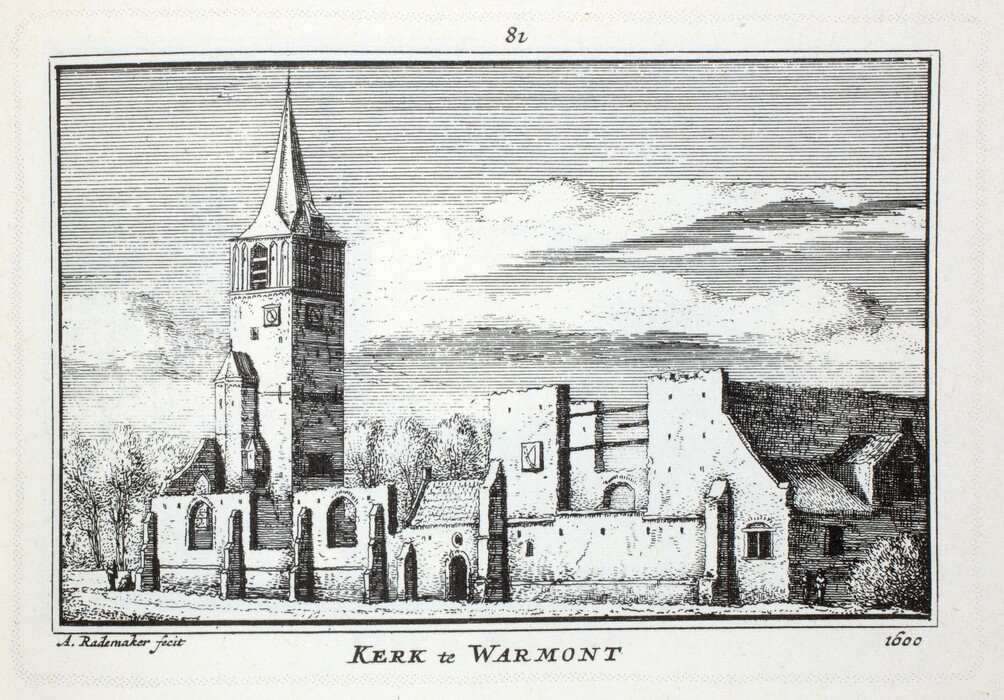

While Van Ostade’s village may be understood as a fanciful creation based on his experiences traveling south of Haarlem, the church tower rising in the background seems to be based on the Oude Kerk at Warmond. A print by Rademaker, Abraham, based on an image from 1600, shows the ruins of this parish church as it appeared after it had been set on fire by the Spanish in 1573 . Van Ostade may have included this church tower, which was restored in 1597 through the efforts of a victorious admiral of the rebel Dutch navy, to orient the scene topographically. Just as the print series of the 1610s was intended to demonstrate the fruits of the Twelve-Year Truce by stressing that people could once again travel in the countryside without fear of attack, so this rebuilt tower, topped by a weather vane in the form of an admiral’s ship, served as a reminder that the freedom to travel in peace had been gained only through the efforts of those who had fought so valiantly against foreign oppression.

The painting, when sold in 1837 from the De Berry collection, was identified as being on canvas. In fact, it originally had been on a wood support [see support, panel] and had been transferred to canvas prior to that date (see Technical Summary). When the old lining fabric was removed and the painting backed by an aluminum panel during restoration in 1982–1983, the old panel-induced craquelure returned, much improving the appearance of the painting. During the restoration it was found that the signature and date, which had read 1645, had been partly reconstructed. Since 1645 seems appropriate for stylistic reasons, this date probably reflected the one originally inscribed on the painting.

Technical Summary

The original support was a horizontally grained wood panel composed of two boards joined horizontally just above the grouped figures. A horizontal check extended from the right edge through several of the figures and the head of the brown horse. Prior to 1837, when the painting was in the sale of the collection of the Duchess de Berry, it was transferred from wood to a fine-weave fabric and lined with the dimensions expanded. The transfer canvas has a small vertical tear in the foreground near the gray horse’s tail. In 1982 the lining was removed and the transfer canvas was relined and marouflaged to a honeycombed aluminum solid support panel consistent with the original panel dimensions.

The artist incorporated a smooth, off-white ground layer into the light tones of the design. He applied paint in thin layers with minimal impasto. Transparent glazes were laid over opaque layers in the upper sky in the dark foreground. The paint craquelure is characteristic of paintings on both wood and fabric supports, although the solid support mounting minimizes the impression of the weave texture.

A thin line of loss exists along the panel join and check and adjacent to a canvas tear that occurred in 1979. Scattered small losses found overall include losses in the signature and date, the beggar woman, and the structures at right. Dark gray stains in the sky were minimized through inpainting when the painting was treated in 1982.