Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century: Portrait of a Man in a Tall Hat, c. 1663

Publication History

Published online

Entry

The identity of this imposing sitter has long been lost, but his dress and demeanor indicate that he was a well-to-do burgher, probably an Amsterdam merchant. The date of the portrait is also unknown, but similarities between this work and Rembrandt’s Syndics of the Cloth Drapers’ Guild of 1662 suggest that the two paintings are not far removed in date. The sitter’s hairstyle and costume, particularly his wide, flat collar with its tassels, are similar, as is the dignified gravity that he projects as he focuses his eyes on the viewer from beneath his wide-brimmed black hat. Even the herringbone canvases that Rembrandt used for these paintings are comparable.

The vigor and surety of Rembrandt’s brushwork are particularly evident in the head. He has modeled the man’s face with broad strokes heavily loaded with a relatively dry paint. Since it is mixed with little medium, the paint has a broken character that enhances the sitter’s rough-hewn features. Stylistically, this manner of execution is broader than that found in the Gallery’s A Young Man Seated at a Table (possibly Govaert Flinck), with which it is often compared, and, to a certain extent, even broader than that of the Syndics of the Cloth Drapers’ Guild, an evolution of style that suggests a date of execution subsequent to these works, perhaps 1663.

Unfortunately, aside from the well-preserved face and the relative disposition of the figure, it is extremely difficult to make precise assessments about this painting. The basic problem is that the original character of the painting has been distorted through flattening, abrasion, and discolored varnish. Infrared examination [see infrared reflectography] reveals that extensive abrasion in the reddish brown background has been heavily restored. The degree to which the massive black form of the man’s robes has been damaged by abrasion and/or reworking, however, cannot be determined. Presumably, this illegible mass once had some definition of form that would have related to the three-dimensionality of the man’s body.

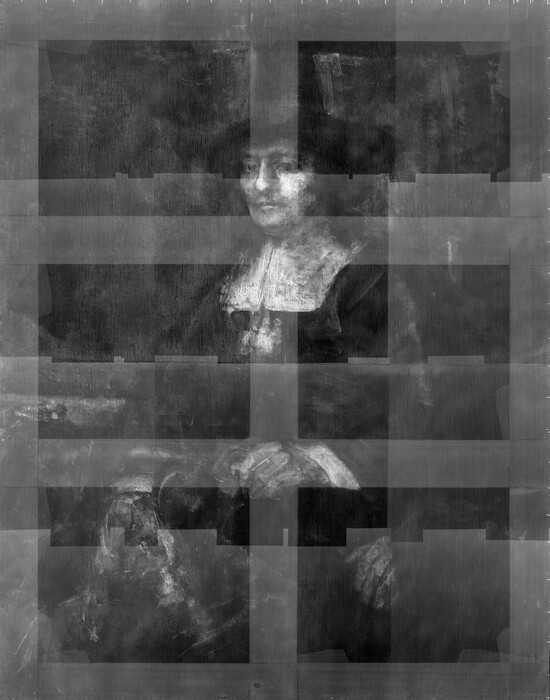

The issue about the condition of the robe is of some consequence because the X-radiographs [see X-radiography] reveal significant pentimenti in the figure’s body. Rembrandt originally had depicted the gentleman with an even longer collar and with his hands in quite different positions. The sitter initially held his left hand higher, at waist level . His cuff was visible, and he held a pair of gloves. The right hand, clasping the armrest of a chair, is harder to read, but it appears as though it used to extend downward in front of the sitter, perhaps resting on or holding some object. To judge from the X-radiographs, these hands were fully modeled. Sharp ridges of lead white paint along their forms indicate that Rembrandt used a palette knife in creating them, a technique not otherwise evident in this painting, but one that Rembrandt began exploiting during the mid-1660s.

As is also clear from the X-radiographs, the different placement of the hands affected the position of the arms. As a result the contour of the body is now much larger than it was originally. It may well be that the sitter initially did not have a cloak draped over his shoulders. X-radiographs also indicate that the crown of the hat was slightly smaller and was silhouetted against a lighter background than at present. At the time that the composition was changed, it is likely that the dimensions of the painting were also reduced.

These changes may have been undertaken to give the sitter a greater presence and added austerity. Moreover, by minimizing the activity of the hands, the head received added emphasis. Unfortunately, large portions of the figure in its present appearance are without visual interest. Because of the thick layers of discolored varnish, it is virtually impossible to determine whether the lack of modeling in the robes results from the condition of the painting or from the quality of the artistic representation. One should not exclude the possibility that someone other than Rembrandt made these changes. In the hands, the only area of the body that can be seen properly, the evidence is not conclusive. The portrayal of the right hand is particularly unsuccessful, and the arm of the chair floats disconcertingly in the midst of the robes surrounding it. Nevertheless, the sitter's left hand is firmly modeled in a manner not unlike that of the face, so an ultimate judgment as to who executed these changes of composition must be reserved until the painting is restored.

Technical Summary

The support is a medium-weight, herringbone-weave fabric consisting of two pieces seamed horizontally at center, 65 cm from the top. The seam protrudes slightly. The support has been double lined using a gauze interleaf, which is visible in the X-radiographs. The tacking margins have been removed. Absence of cusping on all sides suggests a reduction of the original dimensions. Although a thin ground is present, the color could not be determined because it is obscured by a thin, black layer, which is probably a painted sketch. An additional reddish brown underpainting occurs in selected areas such as the face.

Paint was applied as thick pastes with complex layering and lively brushmarking in the features. Brushes and a palette knife were used to apply the paint, and lines were incised with the butt end of a brush. The figure was painted after the background. The red paint of the table continues underneath the black cloak. Several artist’s changes are visible in the X-radiographs. The proper left arm was originally lower at the shoulder, but bent sharply at the elbow with the hand resting just above the sitter’s lap holding a pair of gloves. The proper right arm originally extended downward, ending in a hand that grasped some draped object. White cuffs were eliminated from both sleeves, the left collar tassel was moved to the right, the collar was shortened, and the hat was slimmed.

Numerous small losses have occurred in the white collar and scattered minor losses are located overall. The face is intact save minute flake losses. Severe abrasion in the background and costume has been inpainted. The paint texture has been flattened, probably due to an aggressive lining procedure. A thick, discolored varnish layer covers the surface.

Photo © Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Photo © Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection