NARRATOR:

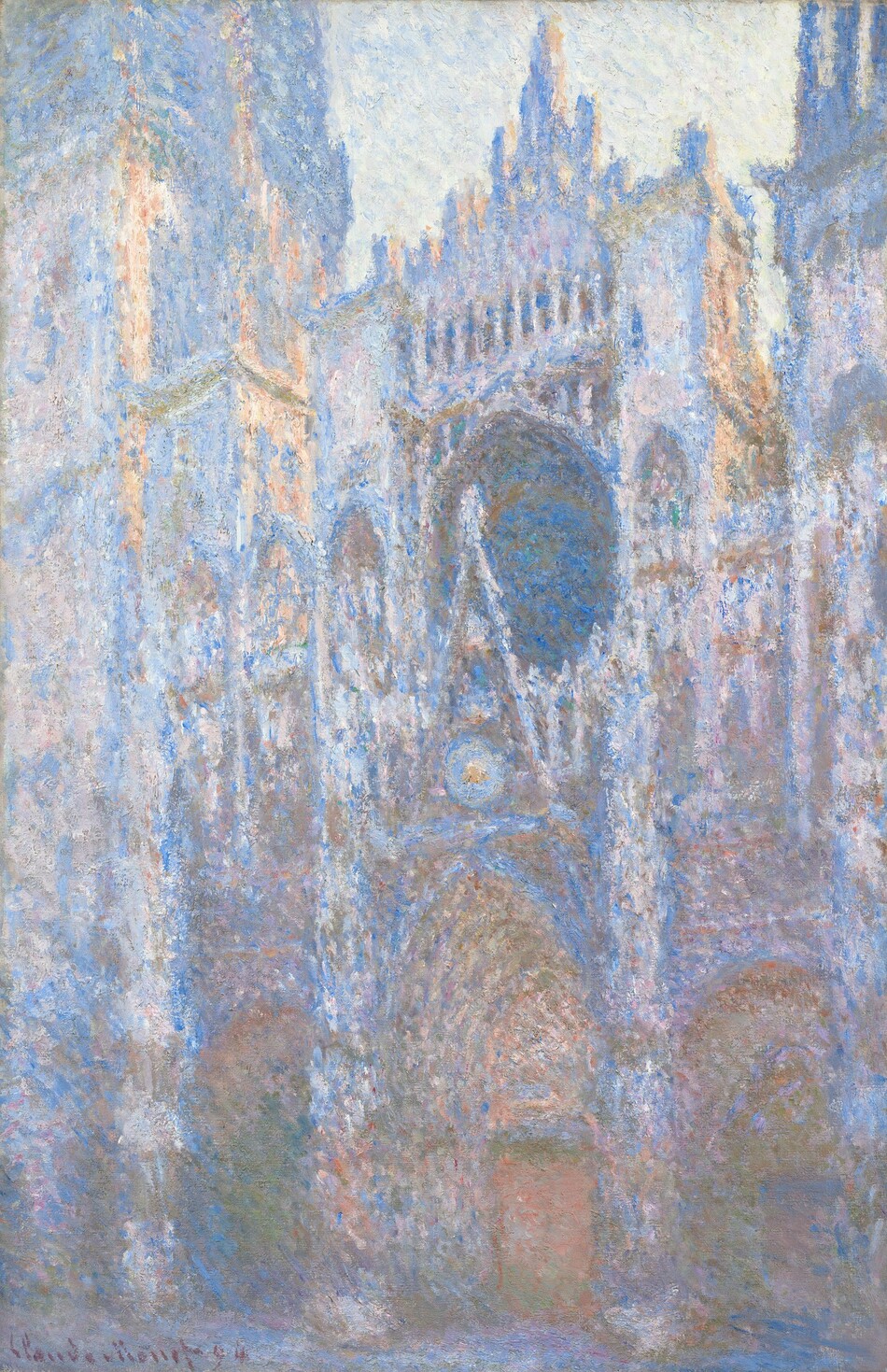

This painting and the one next to it, both by Claude Monet, are part of a larger series -- he exhibited about 20 of them together in 1895. All show the façade of Rouen Cathedral in northern France. The deep blue sky of the brighter picture tells us that it was probably painted in late morning on a clear sunny day. The light is so intense that the façade is almost hard to look at. The darker picture was painted as the light was fading: shadows have begun to swallow up architectural details. The cathedral was chosen not for its spiritual implications, but as a neutral constant to record the effects of light and atmosphere.

PHILIP CONISBEE:

I doubt you’ll find anyone who’s actually experienced what we see in these pictures. Because here the exterior realities, which were the overbearing concerns of Impressionism are enriched by Monet’s own reactions to what he sees. Clearly, he has exaggerated light effects, simplified certain forms, and used color to create mood.

These pictures were certainly finished in the studio, although to the end of his life, Monet perpetuated the myth that he painted directly from the subject to capture exact visual impressions.

NARRATOR:

A series together evokes a spectrum of moods, as light shifts from light to dark and color from pink and yellow to deep greens and blues.

Pictures like these led to Monet’s monumental Water Lilies series, which was intended to create an environment where people could escape the relentless rhythms of life in the modern city.

Series paintings – groups of pictures of almost identical subjects intended to be seen together – are among the most important contributions Monet made to the development of art, exploring a particular motif in varied atmospheric conditions and times of day. He began with haystacks, followed by poplars, and then by facades of Rouen Cathedral, which he painted more than thirty times in the winters of 1893 and 1894.

We know now that at times he worked on multiple canvases simultaneously, shifting from one to another as the light changed. Later he worked on a series together in his studio, and exhibited them as a group. But he never insisted that a series be sold together.