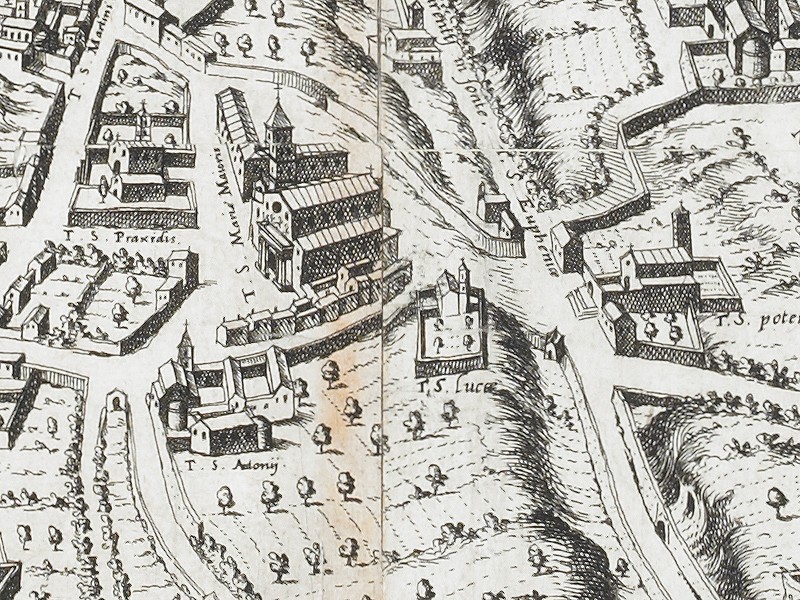

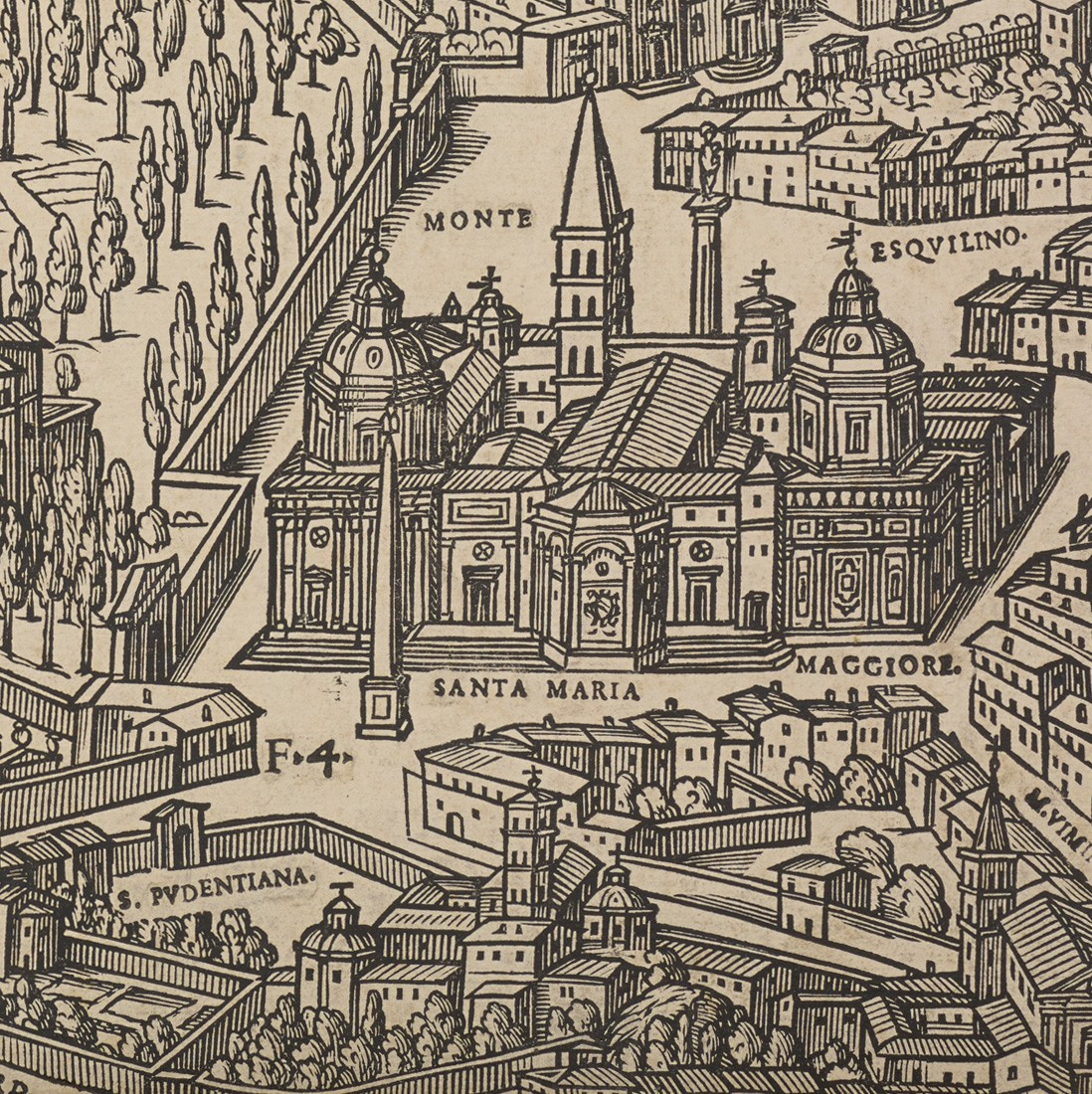

The small Church of San Luca, which once stood on the Esquiline Hill close to the papal basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, was a medieval structure, likely dating to the 13th century. Although most modern accounts of the Università dei Pittori suggest that its activities at the church began in 1478, when the guild’s statuti were promulgated, alternative earlier dates have been proposed. [1] By 1590, the starting point for the History of the Accademia di San Luca research project, the church had already been razed on the express orders of Pope Sixtus V not long after he had acceded to the pontifical throne in 1585. Nevertheless, a partial history emerges from a series of textual, documentary, and visual sources of later date that refer retrospectively to decisions and transactions that occurred at this site.

From all accounts, the church was of modest dimensions. The word chiesuola, used by Girolamo Francini to describe the building in his guidebook to Rome (1566), for example, implies a small structure. [2] It should be noted, however, that despite its size it was worthy of mention in guidebooks (not all churches were). The church was traditionally under the jurisdiction of the neighboring basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore. Work at the church continued for a few decades before its demolition, including pictorial decoration, most or all of which is now lost. A coeval source, Pompeo Ugonio’s manuscript notes on churches of Rome, mentions the church as having a single nave crowned with a barrel vault and adorned with paintings (among which, on the high altar, was the depiction of Saint Luke painting the Virgin, which some scholars contend is the work then attributed to Raphael). [3] Unfortunately, no information about the authors or subjects of the other paintings has come to light.