Still Life with Fruit

1675

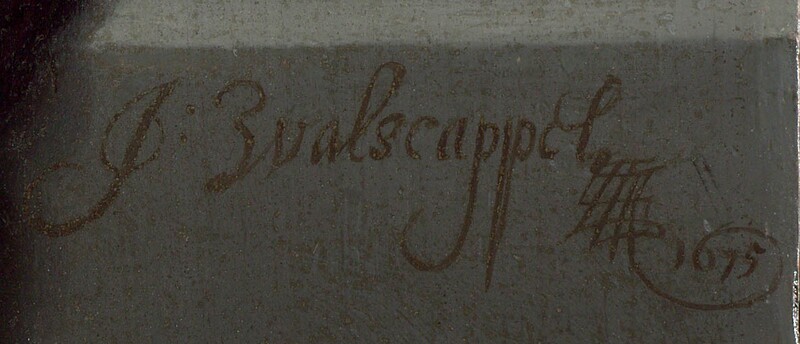

Jacob van Walscapelle

Painter, Dutch, 1644 - 1727

Though modest in size and compass, this still-life painting by Jacob van Walscapelle has a remarkable sense of grandeur. Assembling only a few objects on a plain stone ledge, the artist has conveyed a monumentality of presence usually found in much larger and more complex still lifes. Bathed in soft light, every figural element quietly asserts its essential properties. The Venetian-style glass filled with wine sparkles against the somber dark background. The pomegranate bursting with seeds invites the viewer to imagine its ripe taste, as do the grapes spilling over the edge. In addition to their simple beauty, these items are also part of a long iconographic tradition within still-life painting. The grapes and wine evoke the Eucharist, while pomegranates have complex associations with Christ’s suffering and the Resurrection. In this sense, Van Walscapelle's painting encourages the viewer to contemplate Christ's sacrifice and eventual rebirth.

Van Walscapelle was an accomplished still-life painter, though little is known about the trajectory of his career. Born in Dordrecht in 1644, he established himself in Amsterdam in 1673 and remained there until the end of his life. His approach to still-life painting relates to that of Jan Davidsz de Heem (1606–1684), who similarly relished in the complex and versatile beauty of the visible world. Van Walscapelle’s work nevertheless differed from De Heem’s mature paintings in its compositional restraint and elegant simplicity.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 50-B

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 40 x 34.7 cm (15 3/4 x 13 11/16 in.)

framed: 58.7 x 53 x 5.7 cm (23 1/8 x 20 7/8 x 2 1/4 in.) -

Accession Number

2001.71.1

More About this Artwork

Video: Two-Minute Tour: Clouds, Ice, and Bounty

Join exhibition curator Betsy Wieseman on a two-minute tour of the 2021-2022 exhibition Clouds, Ice, and Bounty.

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

(Etienne Le Roy, Brussels). William Tilden Blodgett [1823-1875], New York.[1] (L. Souty Fils, Paris).[2] (Julius H. Weitzner, Inc., New York).[3] G. Huntington Hartford, II [1911-2008], New York;[4] (sale, Parke-Bernet, New York, 12 December 1956, no. 34); (Newhouse Galleries, New York); sold to Jean McGrail, New York;[5] by inheritance to her daughter; (sale, Sotheby's, New York, 25 January 2001, no. 219); (Berenberg Fine Art Limited, Isle of Man); purchased 11 June 2001 through (Rob Smeets, Milan) by NGA.

[1] The names of Le Roy and Blodgett are given as former owners in the catalogue of a 1938 exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum that included the painting. Blodgett was a businessman and varnish manufacturer as well as a collector, who became one of the founders of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Le Roy (1808-1878) was a restorer, dealer, and expert advisor to the Musée Royal de Peinture et de Sculpture in Brussels, and one of two dealers who in 1870 sold to the New York museum what became its first painting acquisitions, a purchase approved by the museum trustees the following year. It is possible that Blodgett purchased the Walscapelle painting for himself when he was in Europe for several months in 1870 negotiating on the Metropolitan's behalf. On the two men's dealings at that time see: Katharine Baetjer, "Buying Pictures for New York: The Founding Purchase of 1871," Metropolitan Museum Journal 39 (2004): 161-245. The painting did not appear in Blodgett’s estate sale on 27 April 1876, held at Chickering Hall in New York.

[2] The 2001 Sotheby's sale catalogue lists this owner. The company was a successor business to Maison Souty, well-known framemakers during the 19th century in Paris.

[3] Weitzner, whose name is given in the 1956 sale catalogue, was possibly the dealer from whom Hartford acquired the painting.

[4] Hartford was the lender of the painting to the 1938 exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum. He was an heir to the A&P supermarket fortune, and owned an extensive art collection.

[5] The information about Newhouse's purchase and sale of the painting is provided by Meg Newhouse Kirkpatrick, of Newhouse Galleries, in her letter of 17 September 2001 to Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., in NGA curatorial files. The 2001 Sotheby's sale catalogue indicates that Newhouse owned the painting with the dealer Frederick Mont, and the 1969 and 1980 references to the painting associate it with Mont, but the Newhouse records do not reveal any information about Mont's ownership.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1873

Probably Exposition de tableaux et dessins d'anciens maîtres, La société néerlandaise de bienfaisance, Brussels, 1873, no. 339 (supplement of the catalogue's second edition).

1938

The Painters of Still Life, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, 1938, no. 24, as The Pomegranate.

2021

Clouds, Ice, and Bounty: The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund Collection of Seventeenth-Century Dutch and Flemish Paintings, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2021, no. 2, repro.

Bibliography

1873

Decamps, Louis. "Correspondance". Gazette des Beaux-Arts 8 (September 1873): 278 (probably the NGA painting).

Société Néerlandaise de Bienfaisance. Exposition de tableaux et dessins d'anciens maîtres. 2nd ed. Exh. cat. Société Néerlandaise de Bienfaisance, Brussels, 1873: probably no. 339 (catalogue supplement).

1938

Wadsworth Atheneum. The Painters of Still Life. Exh. cat. Wadsworth Atheneum. Hartford, 1938: no. 24.

1969

Bol, Laurens J. Holländische Maler des 17. Jahrhunderts nahe den grossen Meistern Landschaften und Stilleben. Braunschweig, 1969: 377 n. 488.

1980

Vroom, Nicolaas R. A. A Modest Messageas Intimated by the Painters of the "Monochrome Banketje." 2 vols. Schiedam, 1980: 2:317.

Inscriptions

lower right on ledge, in brown paint: J:Walscappel / 1675

Wikidata ID

Q20177657