Still Life with Asparagus and Red Currants

1696

Adriaen Coorte

Artist, Dutch, active c. 1683 - 1707

Adriaen Coorte often focused his compositions on discrete elements placed on a stone tabletop. Whether depicting a bowl of cherries, an arrangement of exotic shells, or a bunch of asparagus, as in this small masterpiece, he imbued his scenes with a haunting timelessness. Here, Coorte balanced the painting by offsetting the bundle of white asparagus with a sprig of red currants and enhanced the composition by using soft light, atmosphere, texture, and a delicate palette of purples, greens, whites, and reds.

Virtually nothing is known about Adriaen Coorte except that he created about one hundred paintings between 1683 and 1707. He apparently lived and worked in Middelburg, the capital of the province of Zeeland in the southern part of the Netherlands, where local collectors acquired many of the artist’s still lifes. He may have been a gentleman "amateur" painter rather than a professional artist, and until the late 1950s his name hardly appeared in discussions of Dutch art. Now, however, Coorte is rightly recognized as a gifted and original master, whose spare and carefully balanced compositions are highly prized.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 50-B

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 34 x 25 cm (13 3/8 x 9 13/16 in.)

-

Accession Number

2002.122.1

More About this Artwork

Video: Two-Minute Tour: Clouds, Ice, and Bounty

Join exhibition curator Betsy Wieseman on a two-minute tour of the 2021-2022 exhibition Clouds, Ice, and Bounty.

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Baroness Irene von der Becke-Klüchtzner. "property of a gentleman"; (sale, Christie, Manson & Woods, London, 8 July 1977, no. 84); (David Koetser Gallery, Zurich); private collection; (David Koetser Gallery, Zurich); purchased 7 October 2002 by NGA.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

2003

Small Wonders: Dutch Still Lifes by Adriaen Coorte, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2003, checklist no. 6, color repro.

2021

Clouds, Ice, and Bounty: The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund Collection of Seventeenth-Century Dutch and Flemish Paintings, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2021, no. 3, repro.

Bibliography

1977

Bol, Laurens J. Adriaen Coorte: A Unique Late Seventeenth Century Dutch Still-Life Painter. Assen, 1977: 68, no. a.

2002

Sutton, Peter C. Dutch and Flemish paintings : The Collection of Willem Baron van Dedem. London, 2002: 87, fig. 13a.

2003

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Small Wonders: Dutch still lifes by Adriaen Coorte. Exhibition brochure. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2003: no. 6.

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. "Adriaen Coorte, Still Life with Asparagus and Red Currants." National Gallery of Art Bulletin no. 29 (Spring 2003): 14, repro.

2006

Bénézit, Emmanuel. Dictionary of artists. 14 vols. Paris, 2006: 3:1357.

2008

Buvelot, Quentin. The still lifes of Adriaen Coorte (active c.1683-1707): with oeuvre catalogue. Exh. cat. Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague. Zwolle, 2008: 32, 43, 57, 64, 96, 97, no. 24, repro.

2014

Wheelock, Arthur K, Jr. "The Evolution of the Dutch Painting Collection." National Gallery of Art Bulletin no. 50 (Spring 2014): 2-19, repro.

2021

Barkan, Leonard. The Hungry Eye: Eating, Drinking, and European Culture from Rome to the Renaissance. Princeton, 2021: 226-228, fig. 5.21.

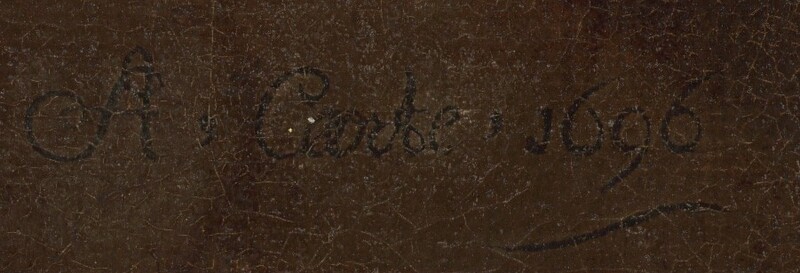

Inscriptions

lower left on front of ledge in black paint: A. Coorte. 1696; on reverse: two circular red seals removed from previous stretcher and set into current stretcher, on each, “IRENE” under a crown, and large, embossed fabric monogram on a piece of fabric that may have been cut from a previous lining fabric, under a crown, ornately intertwined letters, possibly “IBK”

Wikidata ID

Q20177695