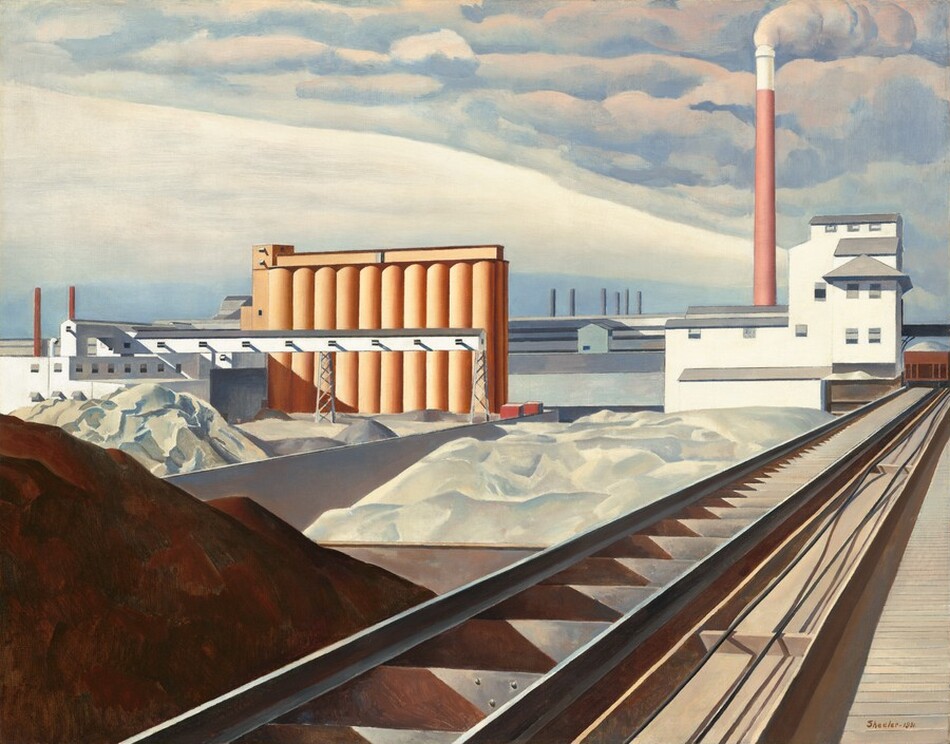

Citadel

1932-1933

Rockwell Kent

Artist, American, 1882 - 1971

Rockwell Kent painted Citadel in 1932 during the second of his three excursions to Greenland. It depicts the most prominent mountain on Karrat Island, which Kent described as a “great citadel.” During the course of Kent’s many far-flung travels, mountains came to occupy an especially prominent place in the artist’s imagination. Kent viewed them at various times as fitting national symbols of liberty, independence, and democracy, as well as spiritual symbols of permanence and eternity. Like Karrat Mountain, Kent—painter, illustrator, adventurer, writer, builder, graphic designer, and activist—presented a roughhewn, complex, multifaceted surface to the world that could be viewed multiple ways from multiple angles.

Citadel was painted thinly over a white ground with the weave of the canvas still visible across its entire surface. The foreground of white snow and background of gray clouds are rendered with simple, fluid, and undifferentiated brushwork. By way of contrast, the dark, jagged mountain is constructed using quick, abrupt, dynamic brushstrokes that register not so much as visual illusions, but as directly applied painted gestures in an almost expressionistic fashion. The sled with figures at the foot of the mountain was added later, sometime between 1933 and 1950. The addition suggests how the objective, documentary aspects of Kent’s Greenland paintings, whether experienced directly or reconsidered in the studio, were always at the service of a much grander romantic, mythical, and philosophical vision of the area. Kent saw the natural world in spiritual terms as “God’s countenance,” not “all that rehash of man’s experience which he terms art, but the eternal fountainhead of all that is beautiful in art and man, the virgin universe.” With its stark, bold, central pyramidal form dominating the canvas, Citadel ranks among the most iconic and abstract of all Kent’s many Greenland paintings.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas mounted on plywood

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 86.36 × 111.76 cm (34 × 44 in.)

-

Accession Number

2013.155.1

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Purchased 1950 through (Macbeth Gallery, New York) by J.J. Ryan [d. 1970], Oak Ridge Estate, Arrington, Virginia;[1] his nephew, Peter H. Brady; purchased 2008 by Edward and Deborah Shein, Seekonk, Massachusetts; gift 2013 to NGA.

[1] Joseph James Ryan was the grandson of Thomas Fortune Ryan (1851-1928), a wealthy businessman and art collector whose bust by Auguste Rodin is in the NGA collection (NGA 1974.29.1).

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1937

Greenland Paintings and Prints: Rockwell Kent, Gallery of Modern Masters, Washington, 1937, no. 13.

1940

Paintings, Lithographs, Wood Cuts by Rockwell Kent, Meinhard-Taylor Galleries, Houston, 1940, no. 7.

[Rockwell Kent], Dayton Art Institute, 1940, unpublished checklist.

1969

Rockwell Kent: The Early Years, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, 1969, no. 55, repro., as Citadel, Greenland.

1985

"An Enkindled Eye": The Paintings of Rockwell Kent, Santa Barbara Museum of Art; Columbus (Ohio) Museum of Art: Portland (Maine) Museum of Art; Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, 1985-1986, no. 61, repro., as Citadel, Greenland.

Bibliography

1933

Kent, Rockwell, and Carl Zigrosser. Rockwellkentiana: Few Words and Many Pictures by R.K. and, by Carl Zigrosser, A Bibliography and List of Prints. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1933, n.p., repro.

1955

Kent, Rockwell. It’s Me O Lord. New York, 1955: color repro. 240.

Inscriptions

lower right: Rockwell Kent; reverse, in black crayon: Landscape Snow

Wikidata ID

Q20192874