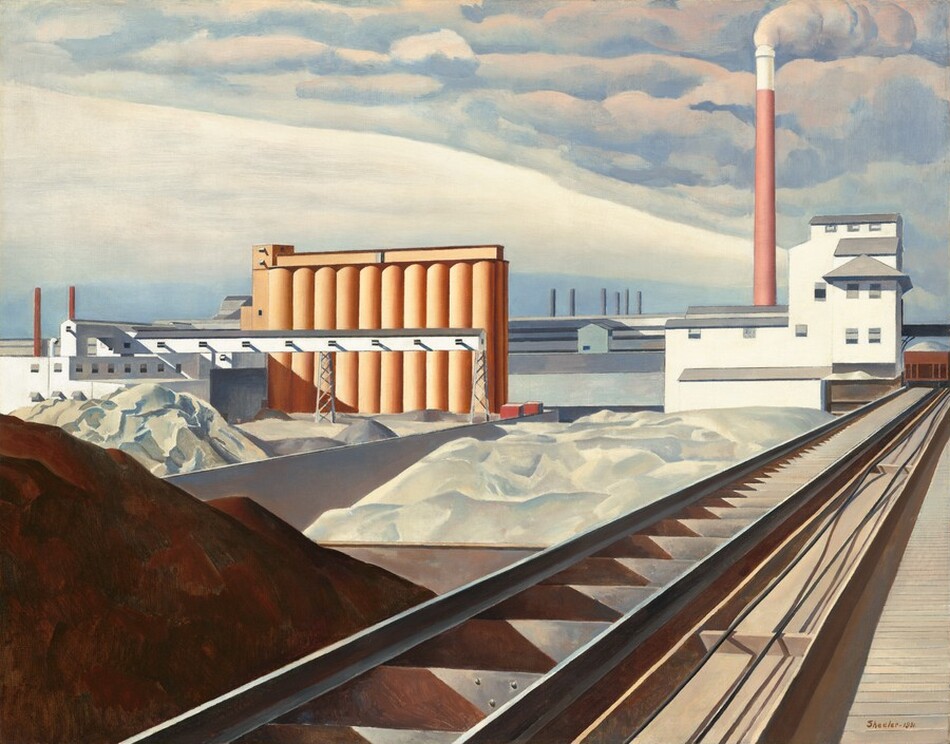

Blue Morning

1909

George Bellows

Painter, American, 1882 - 1925

Blue Morning is the last of four paintings that George Bellows executed from 1907 to 1909 depicting the construction site of the Pennsylvania Station railroad terminal in New York City. Undertaken by the Pennsylvania Railroad and designed by architectural firm McKim, Mead, & White, Pennsylvania Station (more commonly known as Penn Station) was an enormously ambitious project that helped transform New York into a thriving, modern, commuter metropolis. The building project was of considerable interest to the public, and throughout the years that Bellows worked on these paintings, newspapers and magazines regularly reported on the station’s progress.

The three other paintings in the Penn Station series all focus on the gaping excavation pit, and the two that were publicly exhibited at the time, Pennsylvania Excavation and Excavation at Night, were criticized for their “brutal crudity” and “grim ugliness.” Bellows seems to have addressed these criticisms in Blue Morning, because it is a far more aesthetic and impressionistic rendering of the subject. The unusual backlit composition minimizes the pit and instead focuses on the laborers working in the foreground. McKim, Mead, & White’s partially completed terminal building is visible in the distance.

West Building Ground Floor, Gallery G6

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 86.3 x 111.7 cm (34 x 44 in.)

framed: 102.9 x 135.6 x 6 cm (40 1/2 x 53 3/8 x 2 3/8 in.) -

Accession Number

1963.10.82

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

The artist [1882-1925]; by inheritance to his wife, Emma S. Bellows [1884-1959]; purchased June 1956 through (H.V. Allison & Co., New York) by Chester Dale [1883-1962], New York; bequest 1963 to NGA.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1910

Exhibition of Independent Artists, Galleries at 29-31 West 35th Street, New York, 1910, no. 128 (in Paintings Galleries).

1940

Thirty-Six Paintings by George Bellows, Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, Ohio, 1940, no catalogue [according to records of paintings included in the exhibition; this exhibition not listed in the artist's Record Book].

1949

Paintings by George Bellows, H.V. Allison & Co., New York, 1949, unnumbered catalogue.

1956

Paintings by George Bellows, H.V. Allison & Co., New York, 1956, no. 5.

1957

George Bellows: A Retrospective Exhibition, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., January-February 1957, no. 11, repro.

Paintings by George Bellows, Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, Ohio, March-April 1957, no. 8.

1965

The Chester Dale Bequest, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1965, unnumbered checklist.

2010

From Impressionism to Modernism: The Chester Dale Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, January 2010-January 2012, unnumbered catalogue, repro.

2012

George Bellows, National Gallery of Art, Washington; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2012-2013, pl. 22 (shown only in Washington).

Bibliography

1965

Morgan, Charles H. George Bellows. Painter of America. New York, 1965: 93, repro. 321.

Paintings other than French in the Chester Dale Collection. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 50, repro.

1970

American Paintings and Sculpture: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1970: 14, repro.

1971

Braider, Donald. George Bellows and the Ashcan School of Painting. New York, 1971: 49.

1973

Young, Mahonri Sharp. The Eight. New York, 1973: 48, color pl. 14.

1980

Wilmerding, John. American Masterpieces from the National Gallery of Art. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1980: 17, no. 54, color repro.

American Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1980: 25, repro.

1981

Williams, William James. A Heritage of American Paintings from the National Gallery of Art. New York, 1981: color repro. 166, 202.

1988

Wilmerding, John. American Masterpieces from the National Gallery of Art. Rev. ed. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1988: 168, no. 61, color repro.

1990

Kelly, Frankin. "George Bellows' Shore House." Studies in the History of Art 37 (1990): 121-122, 126, repro. no. 5.

1992

American Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1992: 28, repro.

Doezema, Marianne. George Bellows and Urban America. New Haven and London, 1992: 49, 52-55, fig. 19, color pl. 4.

1997

Setford, David, and John Wilmerding. George Bellows: Love of Winter. Exh. cat. Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach; The Newark Museum, New Jersey; Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio, 1997-1998. West Palm Beach, 1997: fig. 15, no. 22.

2007

Haverstock, Mary Sayre. George Bellows: An Artist in Action. Columbus, Ohio, 2007: 31, color repro.

2009

Peck, Glenn C. George Bellows' Catalogue Raisonné. H.V. Allison & Co., 2009. Online resource, URL: http://www.hvallison.com. Accessed 16 August 2016.

2012

Brock, Charles, et al. George Bellows. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2012-2013. Washington and New York, 2012: 9, 23, 89, 92-93, 111, pl. 22.

2013

Corbett, David Peters. The American Experiment: George Bellows and the Ashcan Painters, with Katherine Bourguignon and Christopher Riopelle. London, 2013: 37-39, 46, color fig. 17.

2015

Wolner, Edward W. "George Bellows, Georg Simmel, and Modernizing New York." American Art 29, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 114-116, color fig. 6.

Inscriptions

lower left: BELLOWS

Wikidata ID

Q20191213