The Intruder

c. 1660

Gabriel Metsu

Artist, Dutch, 1629 - 1667

The Protestant Dutch had a reputation for strict rules that defined social conduct. Only on rare occasions, such as a betrothal when a suitor was expected to show passion for his future wife, would a demonstration of emotion be considered proper. In this sumptuous painting, Gabriel Metsu imagines an apparently prearranged "transgression" among the elite of Amsterdam. An officer bursts into a bedroom, where two elegant young women are getting ready for the day. The housekeeper, identified by the keys dangling from her apron, playfully pretends to restrain him. The woman seated in front of the mirror is clearly amused, but the young woman getting down from the bed seems perturbed at being caught in her underskirt. The scene contains a number of objects whose contradictory symbolic meanings would have intrigued contemporary viewers. The sliding of a naked foot into a slipper carries sexual overtones, and the bright red costume signals passion, while the comb held by the woman seated at the table denotes her purity.

Metsu organized this complex narrative scene by arranging his figures diagonally across the picture plane. His subject matter and style was influenced by Gerard ter Borch the Younger (1617–1681), whose Suitor’s Visit is also in the National Gallery of Art. Both artists excelled at depicting human interactions and rendering the satins, velvets, lace, and furs found in upper-class fashions.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 50

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 66.6 x 59.4 cm (26 1/4 x 23 3/8 in.)

framed: 93.4 x 85.1 x 12.1 cm (36 3/4 x 33 1/2 x 4 3/4 in.) -

Accession Number

1937.1.57

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Possibly William van Huls, London; possibly (his estate sale, at his residence by Wilson, London, 6 August 1722 and days following, no. 129, as Ladies in their Bedroom); Edwin.[1] Colonel Gregory Holman Bromley Way [1766-1844], Denham Place, Buckinghamshire;[2] sold to (John Smith [1781-1855], London); sold 26 January 1830 to George John Venables-Vernon, 5th baron Vernon [1803-1866], Sudbury Hall, Derby; (his sale, Christie & Manson, London, 15-16 April 1831, 2nd day, no. 50, as The Importunate Intruder); purchased by (John Smith [1781-1855], London) for Sir Charles Bagot [1781-1843];[3] (his sale, Christie & Manson, London, 18 June 1836, no. 56); Albertus Brondgeest [1786-1849], The Hague, buying for Baron Johan Gijsbert Verstolk van Soelen [1776-1845], The Hague; sold 1846 with the Verstolk van Soelen collection through (John Chaplin, London) to a consortium of Samuel Jones Loyd [1796-1883, later 1st baron Overstone], Humphrey Mildmay [1794-1853], and Thomas Baring [1799-1873], London, and Stratton Park, Hampshire;[4] by inheritance to Baring's nephew, Thomas George Baring, 1st earl of Northbrook [1826-1904], London and Stratton Park; by inheritance to his son, Francis George Baring, 2nd earl of Northbrook [1850-1929], London and Stratton Park; sold March 1927 to (Duveen Brothers, Inc., London, New York, and Paris);[5] sold November 1927 to Andrew W. Mellon, Pittsburgh and Washington, D.C.; deeded 28 December 1934 to The A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, Pittsburgh; gift 1937 to NGA.

[1] Adriaan E. Waiboer, Gabriel Metsu (1629-1667): Life and Work, Ph.D. dissertation, New York University, 2007: 762, no. A-130; Frank Simpson, "Dutch Paintings in England before 1760," The Burlington Magazine 95, no. 599 (February 1953): 41.

[2] John Smith, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters, 9 vols., London, 1829–1842: 4(1833):103, no. 94; 9(1842):524, no. 29, provides the provenance for the painting from Colonel Way through Brondgeest.

[3] See Charles Sebag-Montefiore with Julia I. Armstrong-Totten, A Dynasty of Dealers: John Smith and Successors, 1801-1924, Arundel and London, London, 2013: 21-22, 72, 75-77.

[4] The catalogue of the Verstolk van Soelen collection, annotated with the purchasers of each work, was prepared by Albertus Brondgeest and is dated 29 June 1846. The Metsu painting is number 30 and the purchaser was Baring. See William Henry James Weale and Jean Paul Richter, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Collection of Pictures Belonging to the Earl of Northbrook, London, 1889: 199, 202-203.

[5] Duveen Brothers Records, accession number 960015, Getty Research Institute, Research Library, Los Angeles: reel 124, box 269, folders 14-17. Duveen's representative first saw the painting in 1913 in the front drawing room of Lord Northbrook's London house.

Associated Names

- Huls, William van

- Sale, London

- Way, Colonel Gregory Holman Bromley

- Smith, John

- Vernon, George John, 5th baron Vernon

- Christie, Manson & Woods, Ltd.

- Bagot, Charles, Sir

- Brondgeest, Albertus

- Verstolk van Soelen, Baron Johan Gijsbert

- Chaplin, John

- Baring, Thomas

- Baring, Thomas George, 1st earl of Northbrook

- Baring, Francis George, 2nd earl of Northbrook

- Duveen Brothers, Inc.

- Mellon, Andrew W.

- The A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust

Exhibition History

1834

The Works of Ancient Masters, British Institution, London, 1834, no. 103.

1850

Pictures by Italian, Spanish, Flemish, Dutch, French and English Masters, British Institution, London, 1850, no. 48, as An Interior.

1857

Art Treasures of the United Kingdom: Paintings by Ancient Masters, Art Treasures Palace, Manchester, 1857, no. 1059.

1871

Exhibition of the Works of the Old Masters, associated with Works of Deceased Masters of the British School. Winter Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1871, no. 211.

1889

Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters, and by Deceased Masters of the British School. Winter Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1889, no. 128.

1895

Loan Collection of Pictures, Corporation of London Art Gallery (Guildhall), London, 1895, no. 121.

1900

Exhibition of Pictures by Dutch Masters of the Seventeenth Century, Burlington Fine Arts Club, London, 1900, no. 47.

2010

Gabriel Metsu, 1629-1667, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2010-2011, no. 34, fig. 126.

2017

Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry, Musée du Louvre, Paris; National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin; National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2017-2018, no. 8.3, repro.

Bibliography

1829

Smith, John. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters. 9 vols. London, 1829-1842: 4(1833):102-103, no. 94; 9:524, no. 29.

1834

British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom. Catalogue of the works of ancient masters: the property of His Gracious Majesty William the Fourth, the Most Noble the Marquess of Westminster, and the Right Honourable Sir Charles Bagot, G.C.B. Exh. cat. British Institution, London, 1834: no. 103.

1850

British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom. Catalogue of pictures by Italian, Spanish, Flemish, Dutch, French and English masters: with which the proprietors have favoured this Institution. June, 1850. Exh. cat. British Institution, London, 1850: no. 48.

1854

Waagen, Gustav Friedrich. Treasures of Art in Great Britain: Being an Account of the Chief Collections of Paintings, Drawings, Sculptures, Illuminated Mss.. 3 vols. Translated by Elizabeth Rigby Eastlake. London, 1854: 2:183.

1857

Thoré, Théophile E. J. (William Bürger). Trésors d’Art exposés à Manchester en 1857 et provenant des collections royales, des collections publiques et des collections particulières de la Grande-Bretagne. Paris, 1857: 275-276.

Art Treasures of the United Kingdom. Exh. cat. Art Treasures Palace, Manchester, 1857: no. 1059.

1860

Viardot, Louis. Les Musées d'Angelterre, de Belgique de Hollande et de Russie. Paris, 1860: 155.

Waagen, Gustav Friedrich. Handbook of Painting: The German, Flemish and Dutch Schools. 2 vols. London, 1860: 1:367.

1861

Blanc, Charles. "Gabriel Metsu." In École hollandaise. 2 vols. Histoire des peintres de toutes les écoles 1-2. Paris, 1861: 1:16 (each artist's essay paginated separately) .

1871

Royal Academy of Arts. Exhibition of the works of the old masters, associated with works of deceased masters of the British School. Exh. cat. Royal Academy of Arts, Burlington House, London, 1871: no. 211.

1879

Crowe, Joseph A. Handbook of Painting: The German, Flemish, and Dutch Schools. Based on editions by Waagen and Kugler. 2 vols. London, 1879: 2:399.

1885

Gower, Ronald. The Northbrook Gallery: an illustrated, descriptive and historic account of the Collection of the Earl of Northbrook, G.C.S.I.. The Great Historic Galleries of England 4. London, 1885: 32.

1887

Champlin, John Denison, Jr., and Charles C. Perkins, eds. Cyclopedia of painters and paintings. 4 vols. New York, 1887: 3:250.

1889

Weale, William Henry James. _ A descriptive catalogue of the collection of pictures belonging to the Earl of Northbrook_. 2 vols. London, 1889: 1:55, no. 74, 202-203, repro.

Royal Academy of Arts. Exhibition of works by the old masters, and by deceased masters of the British School. Winter Exhibition. Exh. cat. Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1889: no. 128.

1895

Temple, Alfred G. Catalogue of the Loan Collection of Pictures. Exh. cat. Art Gallery of the Corporation of London, 1895: no. 121.

1897

Roberts, William. Memorials of Christie's: A record of art sales from 1766 to 1896. 2 vols. London, 1897: 1:131.

1900

Burlington Fine Arts Club. Exhibition of pictures by Dutch masters of the seventeenth century. Exh. cat. Burlington Fine Arts Club, London, 1900: no. 47.

1904

Armstrong, Sir Walter. The Peel Collection and the Dutch School of Painting. London, 1904: 34-35.

1906

Wurzbach, Alfred von. Niederlandisches Kunstler-Lexikon. 3 vols. Vienna, 1906-1911: 2(1910):150.

"Metsu." Masters in Art: A Series of Illustrated Monographs 7, part 78 (June 1906): 38, 41, pl. 5.

1907

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. 8 vols. Translated by Edward G. Hawke. London, 1907-1927: 1(1907):314-315, no. 190.

Gerson, Horst. "Metsu, Gabriel." In Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. 37 vols. Edited by Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker. Leipzig, 1907-1950: 24(1930):439-441.

1909

Kronig, Johann O. "Gabriel Metsu." Revue de l’art ancien et moderne 25 (1909): part 2, 213-224, repro.

1912

The Masterpieces of Metsu (1630(?)-1667). Gowans's Art Books. London and Glasgow, 1912: 50, repro.

1926

Collins Baker, Charles Henry. Dutch Painting of the Seventeenth Century. London, 1926: 24-25, color repro.

1937

Jewell, Edward Alden. "Mellon's Gift." Magazine of Art 30, no. 2 (February 1937): 82.

"The Mellon Gift: A First Official List." Art News 35 (1937): 15.

1941

Preliminary Catalogue of Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1941: 134, no. 57.

Held, Julius S. "Masters of Northern Europe, 1430-1660, in the National Gallery." Art News 40, no. 8 (June 1941): 12, repro.

Duveen Brothers. Duveen Pictures in Public Collections of America. New York, 1941: no. 211, repro.

1942

National Gallery of Art. Book of illustrations. 2nd ed. Washington, 1942: 57, repro. 28, 240.

Martin, Wilhelm. Rembrandt en zijn tijd: onze 17e eeuwsche schilderkunst in haren bloetijd en nabloei. Vol. 2 of De Hollandsche Schilderkunst in de Zeventiende Eeuw. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, 1942: 170, 227.

1948

Bernt, Walther. Die niederländischen Maler des 17. Jahrhunderts. 3 vols. München, 1948: 2:no. 516, repro.

1949

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Mellon Collection. Washington, 1949 (reprinted 1953 and 1958): 90, repro.

1960

Baird, Thomas P. Dutch Painting in the National Gallery of Art. Ten Schools of Painting in the National Gallery of Art 7. Washington, 1960: 30, color repro.

The National Gallery of Art and Its Collections. Foreword by Perry B. Cott and notes by Otto Stelzer. National Gallery of Art, Washington (undated, 1960s): 23.

Bernt, Walther. Die niederländischen Maler des 17. Jahrhunderts. 3 vols. 2nd ed. Munich, 1960: 2:no. 516, repro.

1962

Grinten, Evert F. van der. "Le cachalot et le mannequin: deux facettes de la réalité dans l’art hollandais du seizième et du dix-septième siècles." _Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek _ 13 (1962): 170-173, fig. 23.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963 (reprinted 1964 in French, German, and Spanish): 315, repro.

1965

National Gallery of Art. Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. Washington, 1965: 90.

1968

Schneede, Uwe M. "Gabriel Metsu und der holländdische Realismus." Oud Holland 93 (1968): 47, 50.

Gudlaugsson, Sturla J. "Kanttekeningen bij de ontwikkeling van Metsu." Oud Holland 93 (1968): 13-42, 27, repro.

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 78, repro.

1969

Bernt, Walther. Die niederländischen Maler des 17. Jahrhunderts. 3 vols. 3rd ed. Munich, 1969: 2:no. 752, repro.

1974

Robinson, Franklin W. Gabriel Metsu (1629-1667): A Study of His Place in Dutch Genre Painting of the Golden Age. New York, 1974: 56-57, 67, 181, repro. 133.

1975

National Gallery of Art. European paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. Washington, 1975: 232-233, repro.

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1975: 286, no. 379, color repro.

1976

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. "Review of Robinson 'Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667): A Study of His Place in Dutch Genre Painting of the Golden Age' (1974)". The Art Bulletin 58 (1976): 456.

Jongh, Eddy de. Tot Lering en Vermaak: betekenissen van Hollandse genrevoorstellingen uit de zeventiende eeuw. Exh. cat. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1976: 195, no. 3.

1978

Wright, Christopher. The Dutch Painters: 100 Seventeenth Century Masters. London, 1978: 140, color repro.

1979

Bernt, Walther. Die niederländischen Maler und Zeichner des 17. Jahrhunderts. 5 vols. 4th ed. Munich, 1979-1980: 2:no. 805, repro.

1983

Southgate, M. Therese, M.D., ed. "The Cover: Gabriel Metsu, The Intruder." Journal of the American Medical Association 249, no. 6 (11 February 1983): 740, cover repro.

1984

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 287, no. 373, color repro.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 268, repro.

Robinson, Franklin W. The Letter. San Diego, 1985: unpaginated, repro above fig. 8.

1986

Sutton, Peter C. A Guide to Dutch Art in America. Washington and Grand Rapids, 1986: 310, repro. 463.

1989

Tortora, Phyllis G., and Keith Eubank. A Survey of Historic Costume. New York, 1989: 157, fig. 10.9.

1991

Ydema, Onno. Carpets and Their Datings in Netherlandish Paintings, 1540-1700. Zutphen, 1991: 138, no. 129.

1993

Todorov, Tzvetan. Éloge du quotidien: essai sur la peinture hollandaise du XVIIe siècle. Paris, 1993: 76, fig. 45.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 164-168, color repro. 167.

1997

Southgate, M. Therese, M.D., ed. The art of JAMA: one hundred covers and essays from the Journal of the American Medical Association. St. Louis, 1997:140-141, repro. 211, 740, cover repro.

1998

Roberts, Helene E., ed. Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography: Themes Depicted in Works of Art. 2 vols. Chicago, 1998: 1:326.

Tortora, Phyllis G., and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume: A History of Western Dress. 3rd ed. New York, 1998: 215, fig. 9.10.

Winkel, Marieke de. "The Interpretation of Dress in Vermeer’s Paintings." In Vermeer Studies. Edited by Ivan Gaskell and Michiel Jonker. New Haven, 1998: 326-339, fig. 3.

2001

Chapman, H. Perry. "Home and the Display of Privacy." In Art & Home: Dutch Interiors in the Age of Rembrandt. Edited by Mariët Westermann. Exh. cat. Newark Museum; Denver Art Museum. Zwolle, 2001: 145-147, repro.

2003

Waagen, Gustav Friedrich. Treasures of Art in Great Britain. Translated by Elizabeth Rigby Eastlake. Facsimile edition of London 1854. London, 2003: 2:183.

2004

Schavemaker, Eddy. "Eglon van der Neer, 'A Lady, Washing Her Hands'." In Senses and Sins : Dutch Painters of Daily Life in the Seventeenth Century. Edited by Jeroen Giltaij. Exh. cat. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam; Städelsches Kunstinstitut und Städtische Galerie, Frankfurt am Main. Ostfildern-Ruit, 2004: 271-272, no. 76, fig. 2.

Bergvelt, Ellinoor, J.P. Filedt Kok, and Norbert Middelkoop. De Hollandse meesters van een Amsterdamse bankier: de verzameling van Adriaan van der Hoop (1778-1854). Exh. cat. Amsterdams Historisch Museum; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Zwolle, 2004: 35, fig. 28.

2007

Waiboer, Adriaan E. "Gabriel Metsu (1629-1667): life and work." Ph.D. dissertation, New York University, 2007: 230, 762-764 (no. A-130), 1179.

2010

Scholten, Frits. "Metsu's marmer." Kunstschrift 54, no. 6 (December 2010/January 2011): 40, 47, col. fig. 45.

Waiboer, Adriaan E. Gabriel Metsu. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; National Gallery of Art, Washington. New Haven, 2010: 21-22, 125, 126, 128, 130, 131, 156, 167-170, 176, 195, no. 34, fig. 92.

2011

Pergam, Elizabeth A. The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857: Entrepreneurs, Connoisseurs and the Public. Farnham and Burlington, 2011: 313.

2013

Sebag-Montefiore, Charles, with Julia I. Armstrong-Totten. A Dynasty of Dealers: John Smith and Successors, 1801-1924: A Study of the Art Market in Nineteenth-Century London. Arundel and London, 2013: 21-22, 72, 75-77, fig. 36.

2022

Gifford, Melanie, Dina Anchin, Alexandra Libby, Marjorie E. Wieseman, Kathryn A. Dooley, Lisha Deming Glinsman, and John K. Delaney, "First Steps in Vermeer’s Creative Process: New Findings from the National Gallery of Art." _Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art_14, no. 2 (Summer 2022): figs. 4 and 6.

Gifford, E. Melanie, Kathryn A. Dooley, and John K. Delaney. "Methodology & Resources: New Findings from the National Gallery of Art." Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art. 14, no. 2 (Summer 2022): fig. 6.

Inscriptions

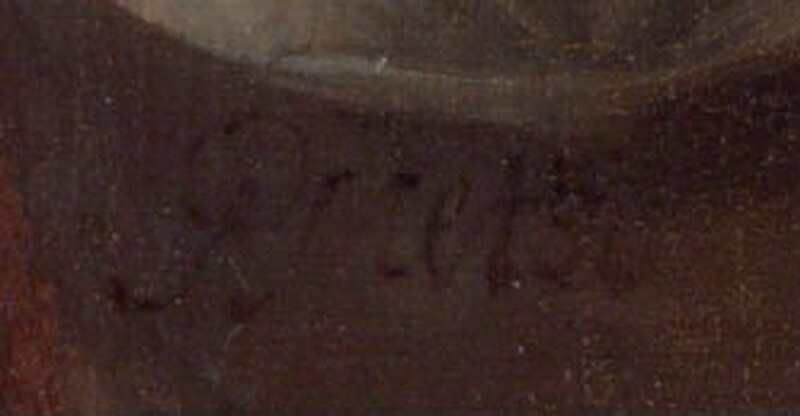

lower center on step to bed: G. Metsu

Wikidata ID

Q20177513