Vanitas Still Life

c. 1650

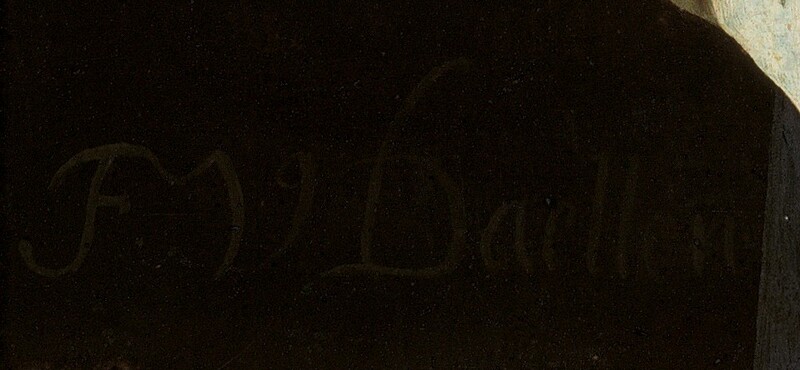

François van Daellen

Artist, active c. 1636 - c. 1651

This delicately rendered painting is one of the finest known works by the Dutch painter François van Daellen. As the Gallery’s painting shows, this specialist in still-life painting possessed a refined manner that allowed him to masterfully imitate the range of textures in the combinations of objects found in such subjects. In the Gallery’s example, which pictures a large skull and femur (thigh bone) atop a scattered assemblage of books and manuscripts, he ably captures bone’s smoothness, paper’s brittleness, and even the ethereal quality of smoke that wafts from the tip of an extinguished candle.

Skulls, bones, and snuffed-out candles often appear in vanitas still lifes, which were designed to convey moralizing messages about the passage of time and the ephemerality of life. Books, indications of intellectual pursuits, are also common elements in vanitas still lifes and may suggest that scholarly and creative achievements last beyond the short span of human life. However, they may also suggest how fugitive and vain man’s accomplishments are in the face of death. As with many objects in Dutch still lifes, books did not necessarily have a single symbolic meaning.

Although Van Daellen painted this work in The Hague, one can easily imagine that Vanitas Still Life belonged to a scholar, perhaps even in Leiden, and that it hung in his study. The illusionistic archway Van Daellen used to frame the work lends the image a certain feeling of intimacy, as, too, does the painting’s small size—strong indications that this work was created for private contemplation and reflection.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 50-C

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on paper laid down on panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 20.3 × 16.5 cm (8 × 6 1/2 in.)

-

Accession Number

2014.58.1

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Private collection, United States; (sale, Bonhams, New York, 6 November 2013, no. 15, as Attributed to Frans van Dalen); (Jack Kilgore & Co., Inc., New York); purchased 20 May 2014 by NGA.

Associated Names

Inscriptions

lower left: F.V. Daellen

Wikidata ID

Q20177362