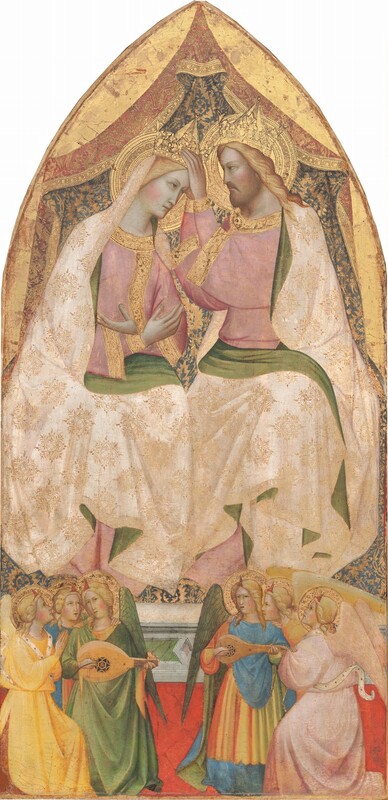

The Coronation of the Virgin with Six Angels

c. 1390

Agnolo Gaddi

Artist, Florentine, c. 1350 - 1396

The Coronation of the Virgin is the final episode in the story of Mary’s life. After her death, she ascended to heaven, body and soul, to be crowned queen by her son. Angels sang and played music in celebration. The subject of the Virgin’s coronation was especially popular in Florence during the last half of the 14th century. Often it appeared at the center of a tripartite altarpiece, flanked by crowded scenes of adoring saints on either side. Very likely, this painting was originally part of such an assemblage.

The subject of Mary’s coronation—an appropriate place for the display of regal finery—complemented a late-Gothic renewal in contemporary Florentine painting. During the later 14th century, artists explored the expressive potential of curvilinear contours and richly decorated surfaces in combination with the naturalistic approach pioneered earlier by the Florentine artist Giotto. The father of Agnolo Gaddi, in whose shop the painter had trained, had been a disciple of Giotto. But here Agnolo has departed from Giotto’s heavier and simpler forms in favor of more slender and refined figures. Mary and Jesus appear on, rather than in the space they inhabit. Profuse patterns appear in the gold brocades of their robes and the rich cloth of honor behind them fills most of the picture plane, drawing our eyes to it. Where Giotto had given his figures a certain solemnity to match their physical weight, the faces of Agnolo’s figures exhibit a gentle elegance and sweetness.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 2

Artwork overview

-

Medium

tempera on panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

painted surface: 161 × 79 cm (63 3/8 × 31 1/8 in.)

overall: 163.2 × 79.2 × 0.7 cm (64 1/4 × 31 3/16 × 1/4 in.)

framed: 172.1 x 87.3 x 7.9 cm (67 3/4 x 34 3/8 x 3 1/8 in.) -

Accession Number

1939.1.203

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

The Hon. William Keith Rous [1907-1983], Worstead House, Norfolk; (sale, Christie, Manson & Woods, London, 29 June 1934, no. 58, as by Orcagna); purchased by (Giuseppe Bellesi, London)[1] for (Count Alessandro Contini Bonacossi, Florence); sold October 1935 to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, New York;[2] gift 1939 to NGA.

[1] Bellesi worked in London as Contini Bonacossi’s agent in the 1930s.

[2] The bill of sale for several paintings, including the Gaddi, is dated 10 October 1935 (copy in NGA curatorial files). The name of the British owner is incorrectly given as the Hon. Keith Bons. See also The Kress Collection Digital Archive, https://kress.nga.gov/Detail/objects/2109.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1939

Masterpieces of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture from 1300-1800, New York World's Fair, 1939, no. 128.

1940

Arts of the Middle Ages: A Loan Exhibition, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1940, no. 59.

Bibliography

1934

Christie, Manson, & Woods. Pictures and Drawings by Old Masters. London, 29 June 1934: no. 58.

1937

Ragghianti, Carlo Ludovico. "Su Agnolo Gaddi." Critica d’arte 2 (1937): 188, pl. 134, fig. 1.

1939

Valentiner, Wilhelm R., and Alfred M. Frankfurter. Masterpieces of Art. Exhibition at the New York World’s Fair, 1939. Official Souvenir Guide and Picture Book. New York, 1939: no. 8, pl. 6.

1941

Preliminary Catalogue of Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1941: 70, no. 314.

National Gallery of Art. Book of Illustrations. Washington, 1941: 105 (repro.), 240.

1942

Book of Illustrations. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1942: 246, repro. 107.

1944

Frankfurter, Alfred M. The Kress Collection in the National Gallery. New York, 1944: 18, repro.

1945

Paintings and Sculpture from the Kress Collection. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1945 (reprinted 1947, 1949): 21, repro.

1950

Gronau, Hans Dietrich. "A Dispersed Florentine Altarpiece and its Possible Origin." Proporzioni 3 (1950): 42.

1951

Einstein, Lewis. Looking at Italian Pictures in the National Gallery of Art. Washington, 1951: 23 n. 1.

1955

Ferguson, George. Signs and Symbols in Christian Art. 2nd ed. New York, 1955: pl. 27.

1959

Paintings and Sculpture from the Samuel H. Kress Collection. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1959: 23, repro.

1960

Labriola, Ada. "Gaddi, Agnolo." In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Edited by Alberto Maria Ghisalberti. 82+ vols. Rome, 1960+: 51(1998):146.

1963

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance. Florentine School. 2 vols. London, 1963: 2:69, pl. 350.

1965

Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 54.

1966

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools, XIII-XV Century. London, 1966: 39-40, fig. 98-99.

1967

Klesse, Brigitte. Seidenstoffe in der italienischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Bern, 1967: 344.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 46, repro.

Boskovits, Miklós. "Some Early Works of Agnolo Gaddi." The Burlington Magazine 110 (1968): 210 n. 5.

1972

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass., 1972: 77, 308, 645, 661.

1975

European Paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1975: 140, repro.

Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370-1400. Florence, 1975: 118, 303, 304, fig. 267.

1977

Cole, Bruce. Agnolo Gaddi. Oxford, 1977: 28-30, 35, 36, 89, 90, pls. 83-85.

1978

Boskovits, Miklós. "Review of Agnolo Gaddi by Bruce Cole." The Art Bulletin 60 (1978): 708, 709.

1979

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Catalogue of the Italian Paintings. National Gallery of Art. 2 vols. Washington, 1979: 1:194-195; 2:pl. 135.

1980

Cole, Bruce. Sienese Painting from Its Origins to the Fifteenth Century. New York, 1980: 14-16, fig. 8.

1984

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 73, no. 13, color repro.

1985

European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1985: 163, repro.

1986

Ford, Terrence, compiler and ed. Inventory of Music Iconography, no. 1. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York 1986: 1, no. 4.

Ricci, Stefania. "Gaddi, Agnolo." In La Pittura in Italia. Il Duecento e il Trecento. Edited by Enrico Castelnuovo. 2 vols. Milan, 1986: 2:572.

1988

Davies, Martin, and Dillian Gordon. National Gallery Catalogues. The Earlier Italian Schools. Rev. ed. London, 1988: 28.

1989

Bellosi, Luciano. "Gaddi, Agnolo." In Dizionario della pittura e dei pittori. Edited by Enrico Castelnuovo and Bruno Toscano. 6 vols. Turin, 1989-1994: 2(1990):471.

Eisenberg, Marvin. Lorenzo Monaco. Princeton, 1989: 56 n. 56.

1991

Petrocchi, Stefano. "Gaddi, Agnolo." In Enciclopedia dell’arte medievale. Edited by Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana. 12 vols. Rome, 1991-2002: 6(1995):426, 427.

Kopper, Philip. America's National Gallery of Art: A Gift to the Nation. New York, 1991: 179, color repro.

1992

Chiodo, Sonia. "Gaddi, Agnolo." In Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon: Die bildenden Künstler aller Zeiten und Völker. Edited by Günter Meissner. 87+ vols. Munich and Leipzig, 1992+: 47(2005):113

1993

Gagliardi, Jacques. La conquête de la peinture: L’Europe des ateliers du XIIIe au XVe siècle. Paris, 1993: 100-101, fig. 99.

1994

Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330-1430. 2 vols. Oslo, 1994: 1:262, 263; 2:punch chart 8.2.

1996

Rowlands, Eliot W. The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: Italian Paintings, 1300-1800. Kansas City, MO, 1996: repro. 63.

Gold Backs: 1250-1480. Exh. cat. Matthiesen Fine Art, London. Turin, 1996: 74, repro. 76.

Ladis, Andrew. "Agnolo Gaddi." In The Dictionary of Art. Edited by Jane Turner. 34 vols. New York and London, 1996: 11:892.

1998

Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Prague, 1998: 132, 481.

2004

Skaug, Erling S. "Towards a Reconstruction of the Santa Maria degli Angeli Altarpiece of 1388: Agnolo Gaddi and Lorenzo Monaco?" Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 48 (2004): 255.

2005

Splendeurs de la peinture italienne, 1250-1510. Exh. cat. Galerie G. Sarti. Paris, 2005: 62, 64, repro. 66.

2016

Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. The Systematic Catalogue of the National Gallery of Art. Washington, 2016: 131-37, color repro.

Wikidata ID

Q20173309